Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

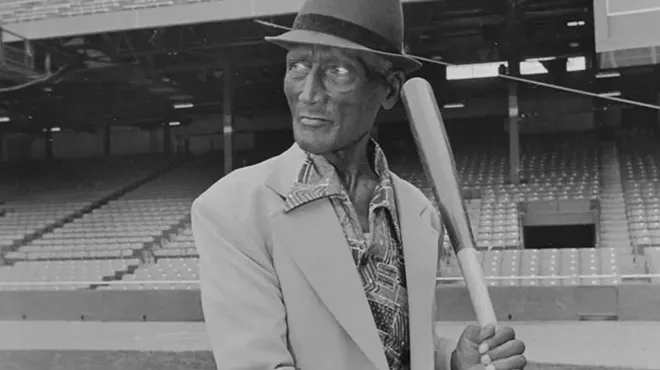

When it came to skill sets in baseball, Willie Mays possessed them all: he was a consistent hitter with power, a marvel on defense, a speedy baserunner, and a clutch performer in all facets of the game. The remarkable statistics he compiled only provide an iota of the excitement he generated over a long and productive career, mostly with the New York and San Francisco Giants.

Mays, 93, died Tuesday afternoon in Palo Alto, California surrounded by friends and family members. His son, Michael Mays, said, “My father has passed away peacefully and among loved ones. I want to thank you all from the bottom of my broken heart for the unwavering love you have shown him over the years. You have been his life’s blood.”

For 22 years, Mays was the tireless and talented lifeblood of Major League Baseball, leaving a lifetime batting average of .301, 660 home runs, 1909 RBIs, 3,292 hits, 2062 runs, and 338 stolen bases. He was an all-star nearly every year, a recipient of 12 Gold Glove Awards, and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, in the first year of his eligibility in 1979. Additional numbers now may be added with the inclusion of statistics from the Negro Leagues incorporated into MLB record books. Mays spent two years in the Negro Leagues with the Birmingham Black Barons.

He was born on May 6, 1931, in Westfield, Alabama, and in his autobiography Say Hey, after a favorite expression of his, written with Lou Sahadi, he said, “I was fifteen, and baseball had come to mean more to me than just about anything else. That summer I played in the Industrial League with my father. He was slowing down by then, and they put him in leftfield while I was in centerfield. My father had always been a symbol of strength to me, strength and ability. I measured my own talent by his. But one day you grow up and you surpass your father.” When his father wasn’t on the ball field he was a porter on the train from Birmingham to Detroit and later at the steel mills. His mother, Ann, was a high school track star.

Not only did he surpass his father’s phenomenal talent, he surpassed nearly all those he competed with and against. His first year with the Barons wasn’t an easy one, most glaringly his inability to hit the curveball. But thanks to advice from his manager Piper Davis he matured as a hitter. “In 1949, he elevated his batting average to .311 and continued to raise it in 1950, hitting .330 with good power,” wrote James A. Riley in The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues. A year later, at 20, he was called up from the minor leagues to the New York Giants.

Mays, then called “Buck,” and later the “Say Hey Kid,” had been the youngest player on the Barons and in 1948 played in the last Negro World Series. “After Negroes got into the big leagues, all the Black fans wanted to see the big league teams,” he wrote in his autobiography. “Ironically, Blacks getting into major league baseball cost hundreds of other Black players their jobs,” he added — to say nothing of the coaches, managers, and owners.

His first year with the Giants in 1951 was much like his first year with the Barons, but after getting only one hit in 25 times at bat, he finally got his first hit and his streak continued just in time to revive the Giants and put them back in the pennant chase against the Dodgers. Most folks remember the dramatic home run Bobby Thomson hit that year off Ralph Branca, giving the Giants the National League Pennant. It was a different story when they played the Yankees in the World Series. Even so, it was a great year for Mays — he was named the National League's Rookie of the Year.

“That first summer in New York was terrific,” Mays said. “I stayed with a couple named David and Anna Goosby. They had a house on St. Nicholas and 151 St.” It was in this neighborhood where Detroiter Dan Aldridge, who lived in Harlem then, first met Mays and spent time with him and his wife, Marguerite, watching television or attending the basketball tournament at nearby Rucker playground. “Willie was really personable and truly related to the community,” Aldridge says in a phone call.

In 1952, he played in only 34 games before being drafted into the Army. After two years in the service, he was back with the Giants to help them in pursuit of another pennant. “I played in my first All-Star game that year,” Mays recalled, “and I never missed another one as long as I played; I made 24 of them and we won 17. At the time I retired, I had played in more All-Star games than anyone else in baseball history.”

Of all Mays’ stellar moments, none is more unforgettable than the catch he made against the Cleveland Indians in the World Series in 1954 at the Polo Grounds. Here is how Mays remembered that sensational catch. “I played [Vic[ Wertz to pull the ball slightly,” he began. “He had been getting around well all day, and in this situation, two runners on, I figured he’d be likely to hit behind them so they could advance. Also, I knew that most hitters like to swing at a relief pitcher’s first pitch, and that crossed my mind as [Don] Liddle was warming up.”

Mays continued, “And that’s what happened. He swung at Liddle’s first pitch. I saw it clearly. As soon as I picked it up in the sky, I knew I had to get over toward straightaway centerfield. I turned and ran at full speed with my back to the plate… I looked over my left shoulder and spotted the ball. I timed it perfectly and it dropped into my glove maybe 10 or 15 feet from the bleacher wall. At the same moment, I wheeled and threw in the same motion and fell to the ground. I must have looked like a corkscrew. I could feel my hat flying off, but I saw the ball heading straight to Davey Williams on second.” The Giants won the series and two former Detroit Tigers were on the Indians’ team — Wertz who hit the ball Mays caught, and Hal Newhouser, who came in as a relief pitcher.

It should be noted that Mays was also a creative showman. Many fans have memories of his hat flying from his head as he rounded the bases or ran down a fly ball. He confessed that the hat flying from his head was something he planned. To accomplish this feat, he often wore a hat too large.

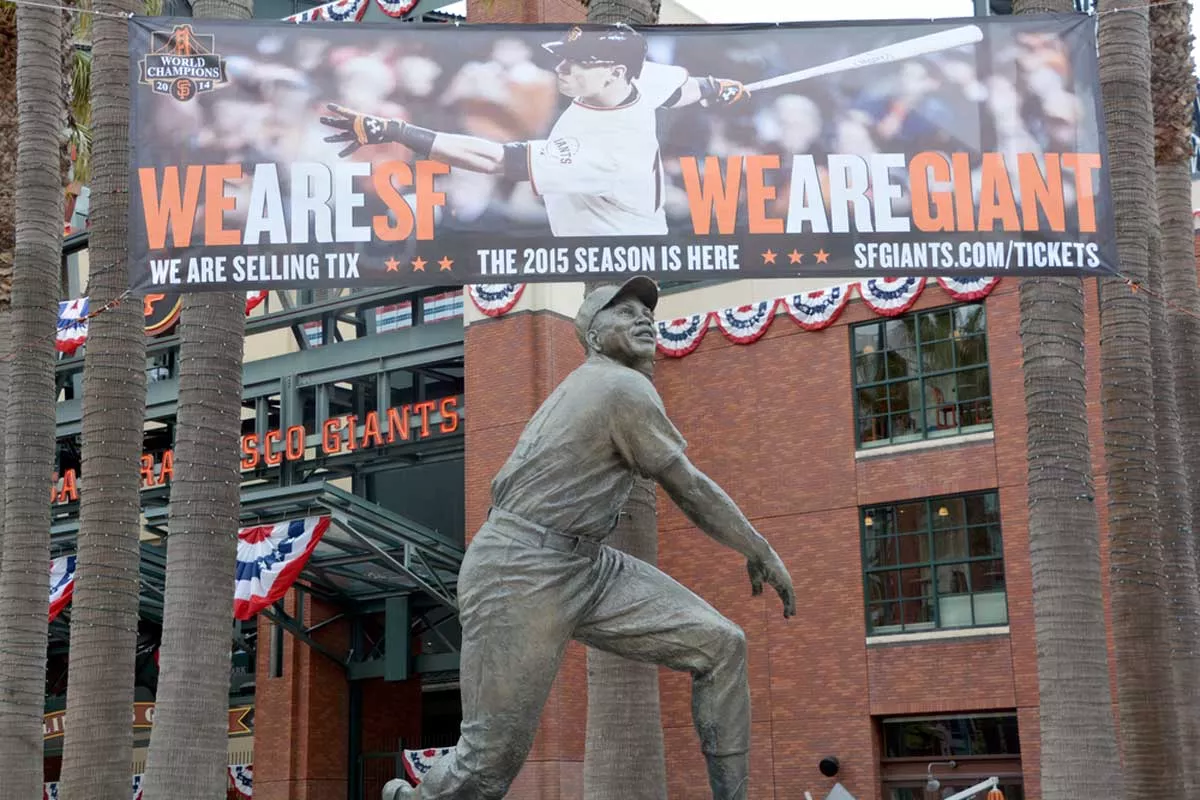

There is not enough space here to recount even a portion of Mays’ often spectacular career, and he died two days before a game between the Giants and the St. Louis Cardinals to honor the Negro Leagues at Rickwood Field in Birmingham and where he and his father played.

Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred spoke at the occasion, noting that “All of Major League Baseball is in mourning today as we are gathered at the very ballpark where a career and a legacy like no other began. Willie Mays took his all-around brilliance from the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League to the historic Giants franchise. From coast to coast ... Willie inspired generations of players and fans as the game grew and truly earned its place as our National Pastime. ... We will never forget this true Giant on and off the field.”

And many New Yorkers in the neighborhood where he lived are fond of recalling those moments when he played stickball with the kids on the block. Whether on the streets or in the stadiums, baseball was all Mays ever wanted to do. “Of course, if you ask me what I’d really like to be doing, the answer is simple,” he said at the close of his autobiography. “All I ever wanted was to play baseball forever. Leo [Durocher] always thought I could.”