Lapointe: Baseball’s statistical correction elevates the stature of Turkey Stearnes

Might the Tigers consider a statue for a star of the Detroit Stars?

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

The story in The Washington Post last week said Negro Leagues statistics are now officially recognized by Major League Baseball. It was illustrated with a photograph of a bronze statue of Josh Gibson that stands outside Nationals Park in D.C.

That’s appropriate. Gibson played in that city with the Homestead Grays. According to MLB’s much-debated decision, Gibson now leads Ty Cobb for first place in career batting average (.372 – .367), and he leads Babe Ruth atop the career OPS list (on-base plus slugging) by a margin of 1.177 – 1.164.

All well and good, I thought. Because they were persons of color, men like Gibson were banned from the “major” leagues of baseball from 1887 until Jackie Robinson re-integrated the sport in 1947. In a way, this statistical recognition is in the pure spirit of reparations — not of money but of respect.

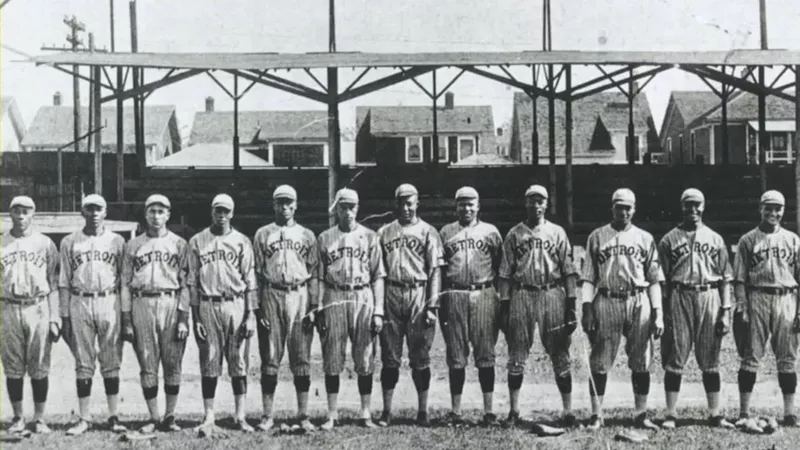

But I wondered about the local angle: Where would this numerical earthquake leave Norman “Turkey” Stearnes, an outfielder for the Detroit Stars a century ago? Stearnes was posthumously inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., in 2000.

Turns out, Stearnes fares very well in the new lists. Under “Career OPS,” Stearnes is ninth, behind Jimmie Foxx (1.037 / 1.003). Under “Career Batting Average,” Stearnes ranks sixth, behind Jud Wilson (.350 / .348).

And in “Career Slugging Percentage,” Stearnes places fifth, behind Mule Suttles (.6179 / .6165). They are in rare company. In this category, the only three ahead of them are Ruth, Ted Williams, and Lou Gehrig. (Full disclosure: I’m very much biased in favor of Turkey Stearnes.)

I met him 45 years ago in Kentucky at a reunion that included several stars of the major Negro Leagues, which existed from 1920–1950. Stearnes’ daughter Joyce Thompson, gives me far too much credit for getting her father elected to Cooperstown in 2000.

Although my Detroit Free Press stories about Stearnes helped elevate his profile, I firmly believe he’s in the Hall because former Tigers announcer Ernie Harwell was on the Veterans Committee the year Stearnes was inducted, and Harwell was one of baseball’s most respected citizens.

Harwell had a quiet way of doing good deeds. I had the good fortune to meet and interview Stearnes in what turned out to be the last weeks of his life. Decades passed. Now, I am a new member — volunteer and unpaid — of the board of directors of the Turkey Stearnes Foundation.

Here’s the pitch: The foundation is sponsoring a baseball event at Historic Hamtramck Stadium at noon on Wednesday, June 19, that will include the third annual “Juneteenth Celebration” and the “Turkey Stearnes Home Run Derby.”

In addition, five scholarships will be awarded by the “Turkey Stearnes Foundation Juneteenth Multidisciplinary Art Contest.” For more information, email bugsydiva8@gmail.com.

That was just the setup pitch; let’s take things a step further. Why don’t the Tigers install in Comerica Park a statue of Turkey Stearnes, just like the one for Josh Gibson in Washington, just like all the other statues in the Comerica outfield?

Stearnes qualifies in many ways. He was an elite Detroit athlete who raised his family here. He migrated here from the South (Tennessee), like many Motor City residents of his generation. He worked at the Rouge plant.

But he’s even more authentic Detroit than that. As a retiree, he often rode the Linwood bus from the West Side to Tigers games at Tiger Stadium and sat in the lower-deck bleachers with his friends.

“I know a lot of boys there, and we discuss things and argue without fighting,” Stearnes told me in July of 1979. “We have a lot of fun.”

Stearnes was 78 years old at the time. I’d just turned 28. I didn’t know he had only weeks to live. He looked good. The secret to longevity, he told me, was, “You’ve got to take care of yourself good. Be careful what you eat, what you drink, where you go, and what you do when you go to those places.”

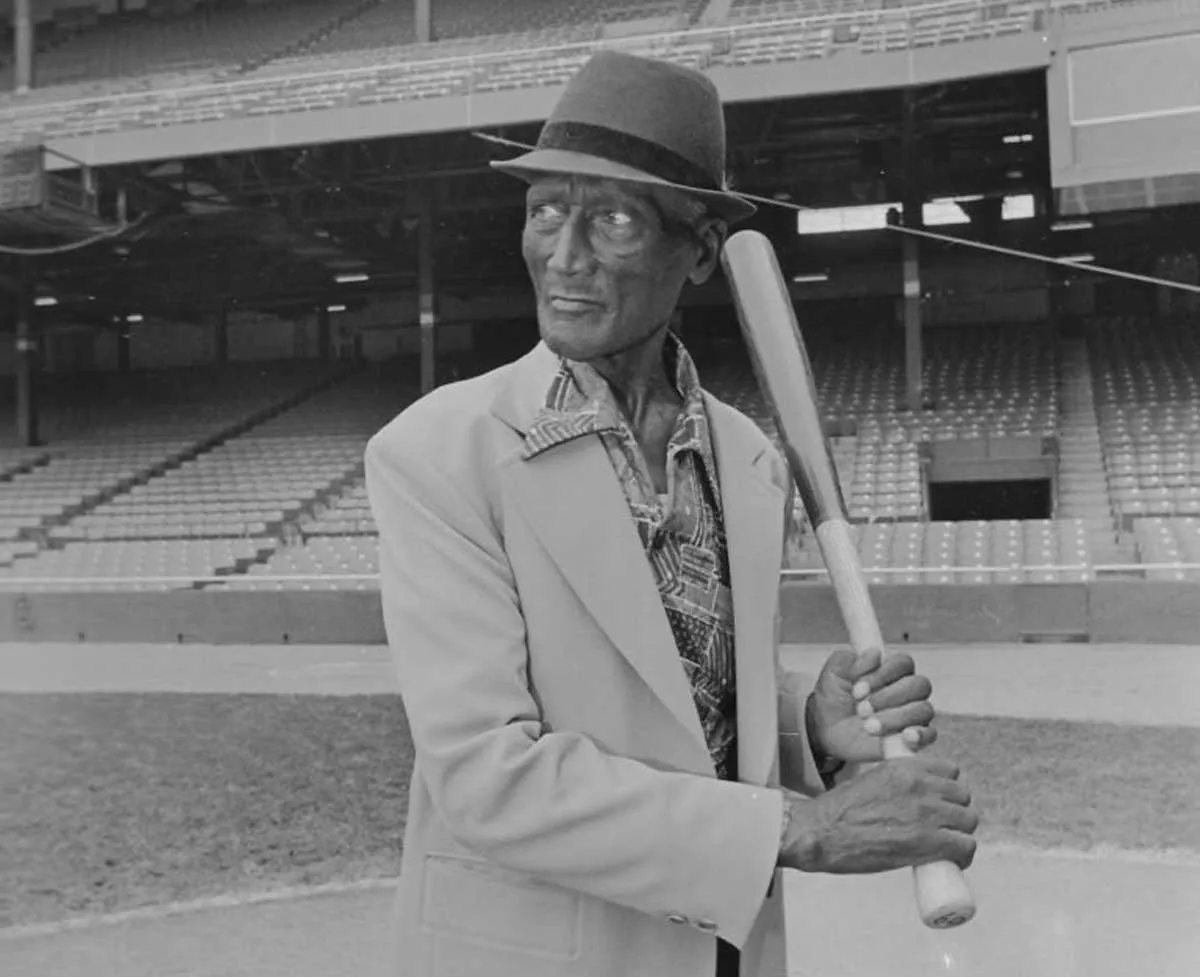

In those weeks, the Tigers were gracious to Stearnes. When I asked, they allowed us to take Stearnes to home plate at Tiger Stadium for a photograph. He took his left-handed batting stance in full dress clothing, including a natty hat, looking out toward the field and the bleachers beyond.

His hands were large and strong, and I remember how his muscle memory snapped back in a flash when he cocked the bat behind his head, eyes bright, fixed on an imaginary pitcher. The photographer was John Collier.

If not quite ghostly, there is something spiritual about the image. A statue of Stearnes — perhaps in this pose and in these clothes — would be an ideal fit for the Comerica outfield as the 25-year-old ballpark undergoes a much-needed renovation. The statue theme is one of the park’s better features.

The ramp behind the left-center field fence already includes statues of Detroit legends like Cobb, Al Kaline, Hank Greenberg, Willie Horton, Hal Newhouser, and Charlie Gehringer. This row of heroes is the park’s center of spiritual energy.

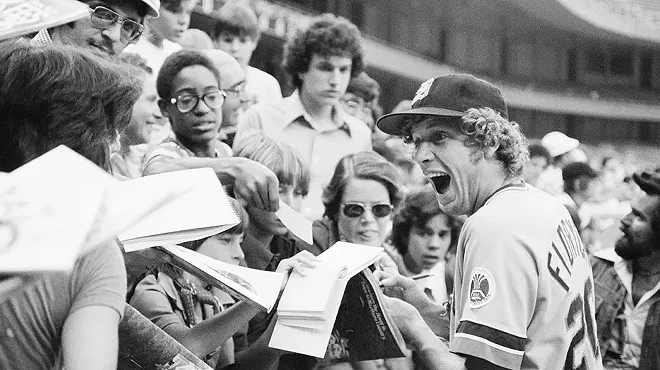

Why not extend the idea to the empty ramp behind the other fence in right-center? It is still without statues. In addition to a statue of Stearnes, put one next to him of Mark “the Bird” Fidrych. One is a Hall-of-Famer who played in Detroit (Stearnes) and the other is one of the most famous and beloved Detroit athletes ever (Fidrych).

The 50th anniversary of the Bird’s sensational 1976 season will come in two years. What better time to further immortalize Turkey and The Bird? Statues such as these would encourage parents and grandparents to pass on baseball lore and its historical and cultural context to future MLB customers.

The Tigers did Stearnes a good deed two decades ago when they dedicated a plaque to him on the outside wall of Comerica after his Cooperstown induction. It’s at Brush and Adams, across the street from football’s Ford Field.

That’s fine. But why leave the face of Stearnes only just outside, looking in? No doubt unintended, there is a symbolism to leaving him on the other side of the wall. Plus, there’s an additional historical and racial undercurrent here that might not be known to Scott Harris, their young president of baseball operations.

But longtime Detroiters certainly will recall that the Tigers were the second-last team to integrate (1958) and that, for many decades, some Black Detroiters felt uncomfortable at Tiger Stadium unless they sat in the bleachers.

That attitude gradually dissipated over several changes in ownership and management; such institutional racism no longer exists. Unfortunately, neither does Black Bottom, the former African American neighborhood that now boasts buildings like Comerica Park.

Had he lived, I would like to have asked Stearnes about those streets and those days: Detroit in the war plants as the Arsenal of Democracy; the deadly rioting of 1943; and all those stories I heard at that long-ago reunion in Kentucky that Turkey was eccentric.

Ray Sheppard — a teammate on the Stars — described Stearnes to me as a guy who sometimes talked to his bats and didn’t like to share them.

“He was a peculiar guy,” Sheppard said. “He was a loner. He didn’t run with anybody or fool around or drink. You couldn’t use his bat or glove. Sometimes he didn’t want a locker by you.”

At the same event, Hall of Famer Judy Johnson told me of Stearnes, “I believe sometimes he carried that bat to bed with him.”

On the airplane back to Detroit, Stearnes sat in the window seat and seemed amazed at his surroundings.

“Lord, we’re above the clouds,” he said. “What man can do.”

He closed his eyes and began to sing song fragments. “Long ago,” he softly sang. “Long ago.”

Just as he seemed to drift off to sleep, he began a tune I recognized. In that it was the Fourth of July, the choice was appropriate.

“My country ’tis of thee,” he sang, “sweet land of liberty …”