Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

There are reasons why police smile when they trot out the booty from a drug bust. And it's not just because they got a bunch of drugs off the street. In addition to drugs, they usually confiscate money, computers, jewelry, guns, cars, bank accounts, homes and more. What makes the police officers' smiles so big is that, other than the drugs, they get to keep everything they took.

Asset forfeiture is the confiscation by police or governments of the alleged ill-gotten gains of crime. If the police deem you to be a drug dealer, or even user, they can pretty much take whatever you have up to $100,000 without having to get anyone's permission. If the amount is more than $100,000, law enforcement must institute a court proceeding in order to keep the asset.

The intent of the law is to take the profit out of crime and financially hamper the criminal element. The problem is that they can keep anybody's stuff even if they are never convicted of a crime. Hell, they don't even have to charge you with a crime to take your stuff. And police are taking plenty in Michigan.

"If you total everything together, in 2009 forfeitures totaled a net of $33,941,000," says state Rep. Jeff Irwin (D-Ann Arbor). "It's a big number."

The real number is actually more than $34 million. The 2010 Asset Forfeiture Report from the Michigan State Police covering 2009 activities states that it is not considered inclusive of all forfeitures, in part because "not all entities reported" and because "federally shared forfeitures do not fall within the guidelines of the statute." Law enforcement agencies are not required to report the amount of forfeitures they seize. So, besides being able to take your stuff without charging you with a crime, they don't have to tell anybody about it either. That's scary.

John Roberts, a medical marijuana patient and caregiver, knows how that works. A couple of years ago, he and a couple of others started what they call the Cannabis Cancer Project in Saginaw. They began producing Simson oil, a preparation of cannabis that adherents say cures cancer and other ailments. Roberts says the oil saved him from a liver transplant he was told he needed due to a 20-year hepatitis C infection.

"I haven't taken a pill in seven years," he says.

Roberts says his group provided the oil for free to cancer patients. He says his home was raided by local police in 2010, and, a couple of months later, the DEA paid him a visit. His grow room equipment was taken, along with about $5,000 in cash, all the cannabis and Simson oil he had, and his bank account. Roberts subsequently lost his home.

"They took everything I owned," he says.

So far he hasn't been charged with anything, although that could still happen.

Jerry Hicks has felt a similar sting. He runs the Higher Learning medical marijuana certification business with offices in Southgate and Detroit. He is also a medical marijuana patient and a member of a compassion center in Allen Park.

This spring the compassion center was raided. Hicks believes that police found records of his membership there. A few days later his personal and business bank accounts were frozen including an account in the name of his then 2-year-old son. The grand total is about $10,000. But the weird thing is that Hicks has not been charged with anything.

"My accounts are frozen and they've never even spoken to me," says Hicks. "I'm mind-blown on this. I would rather have them come charge me with some sort of a crime so I can go to court and get some kind of decision."

You hear these stories again and again. The cops came in and took my stuff but never charged me with a crime. It's rampant across the nation.

Author David Kennedy, in his book Don't Shoot, about innovative police procedures, recounts talking to police who laughed about their forfeiture powers, saying they were in the "business of taking everything you have." He also reported that all of those detectives drove high-end vehicles that had been taken from suspected drug dealers.

Rep. Irwin wants to put an end to that. He's written legislation that he is circulating in Lansing that would make police get a conviction before they can take anyone's assets. He hopes to garner a bipartisan group of co-sponsors and submit it later this fall probably after the November elections.

"People who come into contact with law enforcement sometimes have their possessions taken and auctioned off without being charged with a crime, much less convicted," says Irwin. "One of the first things you learn in civics class is 'innocent until proven guilty.' Drug cases really turn that principle on its head. It's the opposite of the way criminal justice should work in America. ... It's kind of a weighty issue when you think about it, $34 million taken from Michigan citizens and put into increasing the law enforcement effort around the drug war."

According to law, forfeiture funds have to go back into fighting drugs that can be equipment, administrative costs, drug buys. It's kind of a circular thing. Cops take your money and use it to raid more people and take their money. They have a built-in incentive to take property because it comes back to them in two ways. One is that the money goes into their budgets; the other is that they receive federal matching grants pegged to the value of things seized.

"It seeds more forfeitures," Irwin says. "Teams of agents who perform these raids, their future funding is dependent on their success in asset forfeiture revenue. These drug interdiction forces that do the raids and seize the assets, there's a built-in perverse incentive for those agents to be even more aggressive and continue because it funds their operations."

When Irwin does submit his legislation, cannabis activists in Michigan plan an information campaign in support of it. Michigan Moms United to End the War on Drugs (MMU) is one group that has been working with Irwin to craft the legislation. "We want to restore right relations between communities and law enforcement," says MMU cofounder Charmie Gholson.

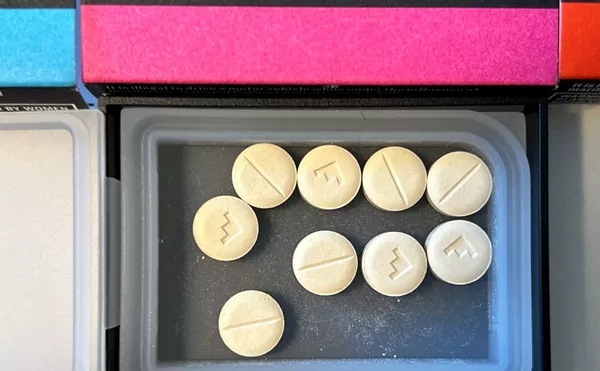

It is indeed a perverse situation that is about as undemocratic as you can get. Which makes one of the beneficiaries of asset forfeitures a very odd connection. The 2010 state police report on forfeitures details that, "In 2009, seizing agencies donated 237 plant growth lights and 274 scales with a combined estimated value of $38,770 to 34 elementary and secondary schools."

Note that the report refers to "seizing agencies" rather than law enforcement agencies. That's a heck of a civics lesson right there.

Larry Gabriel is a writer, musician and former editor of Metro Times. Send comments to letters@metrotimes.com.