Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Page 2 of 3

'Us versus them'

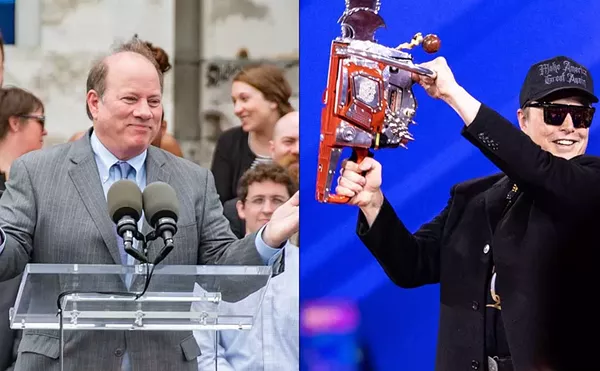

On June 3, the day after Winans threatened violence against protesters, Mayor Duggan and Chief Craig presented him at a press conference as the type of Detroiter who opposed the allegedly violent suburban demonstrators.

"Stay up out of here. Leave everybody in the city of Detroit alone," Winans said in a message to Floyd protesters at the press conference.

Winans was part of a high-stakes public-relations campaign waged by Craig in response to the protests. Its success is critical — should public sentiment in Detroit shift against him and DPD, he could be forced to enact meaningful reforms, as has happened at departments around the country. Moreover, a group of 40 organizations — most of them Black-led — recently signed an open letter calling for Craig's firing. In short, Craig's job is on the line.

The effort has hinged on painting demonstrators as white suburbanites and violent "outside agitators" intent on vandalizing the city. By resorting to the time-tested tactic of pitting Black versus white in a segregated region with a history of racial conflict, Craig created a potent "us versus them" dynamic that helped him secure Black Detroiters' support.

And it has largely worked.

"The protesters don't live here — these people don't live here," says Keith Williams, chair of the Michigan Democratic Party Black Caucus. "How are you going to demand something when you don't live here? Bottom line is we have a sheriff and we have a police chief who grew up in Detroit, and Black folks are comfortable with them."

However, the reality around the protests, who's involved, and who supports it or DPD is much more nuanced than what Craig presents.

Objectively speaking, it's impossible to track where each protester lives, but according to DPD, about 50 of the 130 people arrested on June 2 were from Detroit, though some have said they reside in the city but have suburban addresses on their identification cards. The demonstrators are a mix of Black and white people. Detroit Will Breathe, which still marches almost daily, is largely Black-led, though many of its ranks are also white.

Protesters in the early days damaged some buildings and battled with officers in downtown demonstrations, but never damaged property in the neighborhoods. Since then, clashes with police and vandalism have been rare.

Levels of support are also less clear than Craig has claimed. While he has showcased his backers to the media and declared that the neighborhoods are behind him, protesters say neighborhood residents have come from their houses to join their marches and vent about Craig and DPD.

Moreover, when Craig claims the community is on his side, he's using his own narrow definition of "community," says Michael Stauch, a University of Toledo professor writing a book on the history of policing in Detroit.

In Craig's strict sense of the word, the "community" is those with middle class sensibilities who aren't calling for his resignation, Stauch says. Detroit is actually much larger than just that population.

"People who deviate from that 'community' and how it defines order bear the brunt of policing," says Stauch, who regularly marches with Detroit Will Breathe. "Community gets defined as whoever supports the police."

Meanwhile, as Craig labels protesters "outsiders," only about 23% of his officers live in Detroit, only about half are Black, and the city is run by a white mayor who moved here from Livonia to run for office.

Regardless, the real question is whether Detroiters are buying what protesters are selling.

Detroit Will Breathe is demanding specific law-enforcement reforms, including the prosecution of officers involved in brutality, halting the use of rubber bullets, and an end to the city's use of racially biased facial-recognition technology and the controversial Project Green Light surveillance-camera program. It's also calling for an end to evictions, restoration of water service to those who've lost it, and an end to property foreclosures, among other poverty-related measures.

Though on the surface the latter demands may seem out of place in a protest over policing, they're about raising awareness of the root causes of crime, says Derek Grigsby, a member of anti-foreclosure group Moratorium Now who marches with Detroit Will Breathe.

"We're trying to get people to see and understand that if we had better and more social services, if we had good, free education, housing, if we had jobs and work was a guaranteed right for everyone and those kinds of things ... then crime would go down," Grigsby says.

Some Detroit Will Breathe critics say that older Black, conservative residents are looking for reform, but not that kind, and activists aren't meeting with and including those residents' voices.

"Reform is good, but guess what?" Williams says. "You need to negotiate and sit down and talk with people in the neighborhoods, and what I would do if I was [Detroit Will Breathe] — I'd go to a precinct meeting and listen to how those African Americans interact with the Detroit Police."

White says Detroit Will Breathe is pushing an agenda of the "white left" and criticized it for failing to "localize" the national call for reform. The protesters "have failed to secure buy-in from the residents," he adds.

"That element is forcing the Black community to lock arms against their message," White says. "Now what's being lost is that there needs to be serious change and transformation in the Detroit Police Department. And what the chief has been successfully doing is playing 'us versus them.'"

Detroit Will Breathe leader Tristan Taylor didn't respond to a request for comment.

High crime fosters support for DPD

In July, Detroit police killed Hakim Littleton, a 20-year-old who shot at an officer. It was the first in a string of four DPD shootings during a 21-day period that left three people dead.

The killings, however, didn't spark outrage, as may be expected during the summer of Floyd protests. Instead, Black Detroiters, along with conservative white suburbanites, offered something else on social media during Craig's press conference on the killing — praise for officers and vitriol for Littleton.

"Got trash off the streets."

"Who cares if he was shot he was prolly a dope dealer good one less off the streets."

"Great job DPD when you shoot at police you die, DAMM FOOL." "Love Our Police Chief!!!"

Though activists and Littleton's family called the shooting "an execution" and called for an investigation, a groundswell of support for Littleton never materialized.

The collective reaction contrasts sharply with the outrage directed at officers who have killed Black men in other cities. In short, Detroiters "celebrated death," says White, of the Coalition Against Police Brutality.

"What happened with the shooting of Littleton is the police became empowered, and that leads to three immediate shootings after that," White says. "Now we're living in a city where the police are empowered to shoot, whereas in other cities, you're seeing this pushback."

Craig, however, blamed the shootings on suspects "emboldened" by "anti-police rhetoric."

There's a sense that the level of support for the police is in part driven by the city's high crime rate, while its deep poverty disenfranchises residents. White says the sum of the issues leaves Detroiters unable to think more critically about the department, and there's "a lack of consciousness as a community as to what public safety is, and what we're supposed to be getting from the police department."

The high crime rate likely also plays a role in the divide over which kind of reforms to the criminal-justice system are needed. That question is a key point of contention in the discussion among activists and older residents in the city.

“Now we’re living in a city where the police are empowered to shoot, whereas in other cities, you’re seeing this pushback.”

tweet this

While Detroit Will Breathe is focused on systemic reforms, some older residents just want improvements like faster police-response times. Ann Jones, the conservative Black woman who supports DPD, says reform involves "getting rid of" bad cops, but she wants DPD to have more, not fewer, resources.

"They're putting their lives on the line. Why would we take from them?" she asks. Similarly, Green Acres' Hightower says the department needs more officers and better response times to 911 calls. However, he also supports the idea of non-police units responding to mental-health issues or domestic disturbances.

The reform divide also often forms along generational lines, and White notes that Detroit's population is older. He says the likelihood of selling an elderly Black woman in Detroit on the type of reforms Detroit Will Breathe is pushing are "slim to none" because older residents are more concerned about safety.

"What they want is police to protect them, because they just don't want to get hurt," White says. "If you ask that 90-year-old lady about criminal-justice reform, she's gonna say, 'Man, I couldn't care less about that.' But if you ask her, 'Do you want the cops to come when you call?' She'll say 'you bet.'"

Grigsby sees another factor at play — fear. Detroit is a majority Black city, and Black people have endured centuries of racism. They're "a little afraid to go against a massive entity like the police department."

"In majority-white towns, people are supporting Black Lives Matter and more than willing to protest and demand change openly, but whites haven't had that background of terror that we faced in this country," Grigsby says.