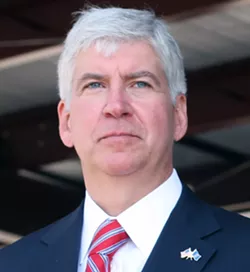

It's hard to remember now, but there was a time, long ago, when people thought Rick Snyder was a principled moderate.

That was seven years ago, before we learned that he'd usually sign a tattered maple leaf if the right-wing majority in the legislature blew it onto his desk.

You might not be able to justify his doing that, but you could make some kind of a Kissinger-like case for needing to do that out of Realpolitik as he plotted his political future.

Except that, well, after the poisoning of Flint, our governor really doesn't have any political future. He'll finish up his term and slink back to Gun Lake, or Ann Arbor.

He ought to know that nobody is going to appoint or elect him to anything, ever — which actually should be an immensely liberating experience. He should now see himself as totally free to do the right thing, a luxury many politicians never achieve.

What's to stop him? Snyder's a multi-millionaire, unlike John Engler or Jim Blanchard when they left office, and doesn't need a job as a lobbyist or industry spokesman.

Naturally, most readers of this column might often bitterly disagree with Snyder on what "doing the right thing" was. The list of his betrayals of the best interests of the citizens stretches from his right-to-work to a truly horrible bill last month that has been described as the U.S. Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United decision on steroids.

The whole point of Senate Bill 335 was to allow unrestricted and hidden spending by outside, so-called "independent" groups to influence elections.

Everyone who really cares about good government urged him to veto the bill, which he quickly and happily signed.

But what was really shocking was that last month, Snyder not only betrayed the people but himself, with a cowardly refusal to take a stand on one of the few issues where he had risked the political capital to do the right thing before.

Four years ago, Snyder worked hard to persuade the legislature to accept Washington's offer to expand Medicaid health care coverage to those who had a household income of just slightly more than the poverty level.

The deal was an unbelievably good one. The cost to Michigan was nothing for the first few years, and never would be more than 10 percent of the total. In return, hundreds of thousands got health care who hadn't had any.

In any kind of rational political universe, this would have been adopted instantly, on a unanimous voice vote. But many Republicans were so consumed with hating "Obamacare" that they would do nothing to take advantage of any of its provisions, even one that clearly helped so many people.

But Snyder fought for it — and won. "This isn't about the Affordable Care Act," he told lawmakers then. "This is about one element we can control in Michigan that can make a difference in people's lives."

Within an astonishingly short time, 600,000 Michiganders had signed up for health care. Employers suddenly had a healthier workforce.

But last month, Congress made another serious run at destroying the Affordable Care Act. The so-called Graham-Cassidy bill would have, over the next nine years, phased out all funding needed to keep folks on Medicaid.

That meant they would no longer have health care, unless Michigan lawmakers were willing to pay for it ourselves.

Instantly, nearly every major health association and agency from Blue Cross to the American Medical Association came out to oppose Graham-Cassidy. So did conservative, yet realistic, GOP governors like John Kasich of Ohio and Chris Christie of New Jersey, and others.

But not Rick Snyder. Jay Greene, Crain's Detroit Business health care reporter, was first to report Snyder's hard-to-believe weenietude on his blog two weeks ago.

When Greene called the governor's office to ask how he stood, he was given a statement saying, "We are still reviewing provisions of the bill and how it might affect Michigan." In what probably wasn't an attempt at sardonic humor, they added "Feel free to check back next week for the governor's thoughts."

Check back, that is, after the issue was settled.

Snyder's indecision seems baffling, since he knows better — and should know how little use Donald Trump has for him.

Michigan's governor didn't endorse Trump last year, even after he was the GOP nominee. Trump made it clear in May that he was in an unforgiving mood. He booted Snyder off his Council of Governors in May, noting, "I never forget."

Trump did then ask Snyder condescendingly if he would like to join him in a photo "even though you didn't endorse me."

So to recap — Snyder has no prayer of getting anything from Trump, and knows how devastating losing expanded Medicare would be to our state. His political career is over.

Yet he didn't even have the guts to say he opposed Graham-Cassidy. This was, by the way, at a point when it appeared they might have won over the slowly dying John McCain, whose best friend in the Senate is Lindsay Graham.

But McCain, who may be embarrassed that he had briefly endorsed the creature in the Oval Office, did the right thing. Snyder, who was in elementary and middle school back when McCain was a prisoner being tortured, did not.

When Snyder was elected governor seven years ago, many of those covering him felt they didn't know who he really was.

Now, it seems he may not know either.

Betsy DeVos may not be wrong here

You aren't likely to catch me saying anything good about Betsy DeVos' anti-public school approach as Secretary of Education.

Her appointment to that job was a slap in the face to thousands of public school teachers who have devoted their lives to trying to prepare children for the future, even as right-wing ideologues have been making those jobs harder, not to mention lowering their salaries and benefits.

Everyone who cares about education is right to scream about that — especially any policies allowing more for-profit companies to run "charter" schools funded by the taxpayers.

Recently, however, DeVos also came up with new guidelines for handling campus sexual assault cases. Liberals immediately howled that she wanted to roll back the clock to an era when women were cuts of meat for the frat boys to enjoy.

Well, not exactly. Her guidelines are meant to be only temporary, but seem meant to restore something like common sense. For example, they allow the use of mediation and an "informal resolution" of any complaint, if all parties agree.

Nobody should ever be able to get away with forcing sex on someone else, period. But relationships between people are often complex, and no matter what the alleged crime, assuming someone is innocent before being proven guilty is, after all, the essence of American justice.

That's not to say DeVos' guidelines are perfect. But as I wrote here on April 19, you need only to look at Laura Berman's spellbinding story in Bridge Magazine, "An Unwanted Touch," to see an example of the current policy run amok.

The bottom line on this, as on about everything else, is that ideology of any kind is no substitute for common sense.