Earlier this month, the New York Times published an expose on Google Map's mysterious practices of renaming neighborhoods in cities across the United States — to the bewilderment of the people living in these areas. Whether it was mistakes made by the tech juggernaut's researchers or the failure to probe the legitimacy of a name market-tested by well-funded local development groups to bolster the allure of the next up-and-coming yuppie hotspot, what resulted is a status quo where the consumer culture takes what Google gives us at face value.

In the case of Detroit, Google scraped bad data to configure a map of the city's neighborhoods. The primary source, a 2002 map created by urban planner Arthur Mullen, includes a transposition error of the Fiskhorn neighborhood that now has etched its digital footprint as "Fishkorn." The name caught on, and "Fishkorn" is now found in real estate listings and food delivery sites. An optometrist from Novi told the NYT the name "rolled off the tongue."

To remedy this, the city's Department of Neighborhoods generated their own neighborhood map, but this is an evolving project. As it stands, there is no official neighborhood map. (The city adopted a district map in 2012, but people tend to be unaware of what district they are in, let alone identify where they live by it.)

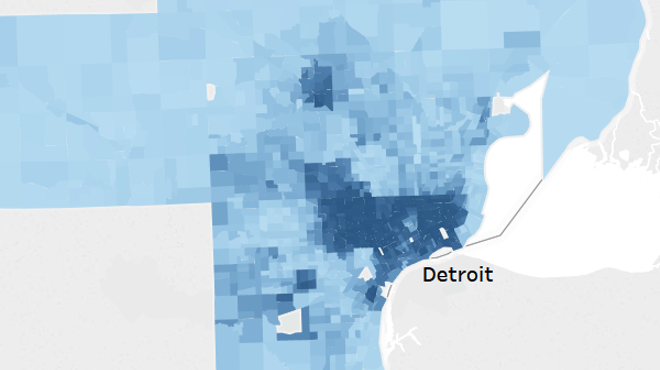

Mullen's map for the city has been one of many attempts to accurately map Detroit's neighborhoods. The US Census Bureau's census tracts define only 54 unique neighborhoods, which isn't really used anymore. In 2013, Loveland Technologies generated its own neighborhood map of nearly 100 neighborhoods, using parcel-by-parcel city data. But for many residents, none of these maps reflect Detroit's complex neighborhood geography and its contours.

Mullen, the urban planner whose 2002 neighborhood map now lives in infamy, saw the project as an opportunity to fill a serious information gap with Detroit's neighborhoods.

"I saw it as an issue or a weakness," Mullen says. "I saw it as a project to get people to talk about neighborhoods and help create an iterative process to help get that map made. I'd hope it'd help start and build an appreciation and identity. The basis for strong cities

If you ask a Detroiter where they're from, you'll likely elicit a hodgepodge of answers: a local landmark, like a church; highly trafficked cross streets; zip codes; or, broadly, whether they live on the east side or the west side of Woodward Avenue. It's common knowledge that Detroit lacks strong neighborhood identification compared to say, a city like Chicago. There's an unevenness to the neighborhood landscape. Some neighborhood boundaries have changed unbeknownst to the long-time residents, as in the case of the McDougall-Hunt neighborhood. Large swaths of the area northeast of Hamtramck have been the austere moniker of Airport Subdivision.

Google Maps shapes the outsider's perceptions of what the neighborhoods are and how we navigate them, but the onus of responsibility to "get it right" falls on the company insofar as what we're giving them to work with. Expectations should be low for faraway Silicon Valley to prioritize community engagement.

In the disinformation age, bad data on its own is certainly a red flag, but that's not at the heart of the matter. The false appearance of the accuracy of Google Maps' poorly sourced version of the city's neighborhood maps leads to the rising concern for residents that their communities are rendered as a blank space.

What's compelling about this absence of neighborhood definition are the forces, historical and contemporary, underpinning the current state of affairs.

"Before, the neighborhoods weren't so well defined," says Alex B. Hill, founder of DETROITography, a blog that archives analytical and historical maps of Detroit. "They weren't hard and fast places that were understood. If you had a neighborhood organization or association or an economic development group, you were more likely to have a well-named neighborhood and a well-defined neighborhood. But if not, you were blank on the map."

In the postwar period, urban planning, some city historians have argued, was weak at the time, and the Detroit City Plan Commission was discriminatory against the city's black residents. The Urban Renewal period that started in the '40s (or dissenters of the day dubbed as "negro removal") refers to a set of policies born out of the Housing Act of 1949, which put millions of dollars into the pockets of developers tasked with clearing the slums to make space forIf you ask a Detroiter where they're from, you'll likely elicit a hodgepodge of answers: a local landmark, like a church; highly trafficked cross streets; zip codes; or, broadly, whether they live on the east side or the west side of Woodward Avenue.

tweet this

commercial buildings. It disenfranchised thousands of black residents at the time and led to the destruction of many vital institutions. During this period, the historic Black Bottom neighborhood was decimated to make way for Lafayette Park.

The construction of the highways cut through major community hubs intensified disenfranchisement. Property owners who wanted to move couldn’t because of the impending highway construction. A multi-year waiting period led to struggles in selling their properties.

Today, persistent population loss and the loss of homes due to tax foreclosures has led to

“Even if a younger resident was not alive to witness that displacement, the meaning of words like renewal, redevelopment, revitalization, and rebirth for many long-term Detroiters reads as the latest chapter in a history of targeted disinvestment and disenfranchisement in Black communities”, writes sociologist Meagan Elliott in her dissertation, "Imagined Boundaries: Discordant Narratives of Place and Displacement in Contemporary Detroit.”

What are the stakes at play if not every community area is given a name, nor its boundaries precisely defined? Neighborhood identities are not a static thing, so the notion that there needs to be a neighborhood map that is 100 percent accurate may not necessarily be the primary end game, at least according to Hill.

"There's a presumption that a map needs to define every neighborhood," he says. "I don't think that it needs to. A lot of cities have taken upon themselves, like Boston and Chicago, to define every area of the city. [In Detroit], there is very much a focus on housing and real estate. There is a dangerous opportunity for someone with a lot of money to come in and define a neighborhood and just run with it. There's also a great opportunity to have stronger community engagement process with block clubs and organizations."

The much publicized (and under-interrogated) idea of the Detroit renaissance has captured the country's collective imagination, and local, well-funded entities have profited from co-opting this narrative and rebranding certain neighborhoods. In 2015, a part of Southwest Detroit was dubbed "Springwells Village" by the Urban Neighborhoods Initiative. Southwest Detroit activists called foul on the new name for the lack of community input, blasting it as "a neocolonial moment." Meanwhile, Midtown Detroit, once known as the hardscrabble Cass Corridor, is one of the few neighborhoods that's seen considerable investment in its courtship of new residents and businesses, predicated on pushing Midtown as a brand.

If the basis for strong cities are strong neighborhoods, does having a name denote strength? And is the opposite true? It’s not so cut and dry for Katrina Keedy-Watkins, the executive director of the Baily Park Project.

“Even if a neighborhood doesn’t have a name or an official identity, people still care about their neighborhood and they’re still there," Keedy-Watkins says. "We care about our neighborhood as much as a neighborhood where the city is focusing."

There's a general consensus among McDougall-Hunt's community members that their street borders are Gratiot Avenue, Mt. Elliot Street, and Vernor Highway, which form a triangle boundary. Here, Google Map's boundaries of the area are correct; it's the city map that's been scrutinized.

In the Department of Neighborhoods' neighborhood map, those boundaries have expanded to include a sliver of land north of Gratiot. Even though it is a relatively small piece of land, it has become a point of contention between the residents of McDougall-Hunt and those living in the community north of Gratiot.

"They said they did not want to be part of McDougall-Hunt," Keedy-Watkins says. "They wanted to come up with their own name for their own community."

Rich Conklin, a resident living north of McDougall-Hunt's Gratiot border along with a few other area residents, formed the East Canfield Neighborhood Association. Conklin quickly points out there's already an East Canfield neighborhood on the city's neighborhood map two miles east of their location.

"The situation is a bit confusing," he says. "It's funny. When you describe to people where you live, the more you give clues to people, the more uncertain they know where you are."

"It's incorrect. It's erroneous. How did we suddenly get called McDougall-Hunt?" Conklin says. He recalls in a recent community meeting that when a city official was asked what the neighborhood name was, she said she didn't know. The room then erupted in debate.

"'No, it's Black Bottom!' one person said. 'No, it's Poletown!'" he remembers. It's unclear what the city's role is in revising the current neighborhood map or what the process is to file a request to a name change or propose a new name. The city's Department of Neighborhoods did not respond to those questions for this story.

Conklin and other residents defined their community boundaries as Mack Avenue to the south, Warren Avenue to the north, Dequindre Street to the west, and McDougall to the east. There was also growing

"Nobody in our neighborhood wanted to be called Greater Eastern Market," he says. "They called us a gem. You'd hardly refer to it as a gem. It's a great neighborhood, but you wouldn't call it that. If there used to be 100 houses on the block, there are ten left. There's such a massive exodus from this neighborhood starting in the '70s. We don't want to see more meatpacking warehouses."

The Airport Subdivision, located east of Hamtramck, is a large swath of land that consists of several unique and distinct communities that also do not have names. They fall under the umbrella term because of its proximity to the city airport. Pastor Alonzo Bell of the Martin Evans Missionary Baptist Church grew up in on Gratiot Avenue and Belvidere Street. He also worked for Detroit Public Schools for almost 15 years. He identifies where he lives as the airport district, whose borders are Conner Street up to Six Mile Road, then north to Gunston Street to Harper Avenue and then back to Conner.

In the past, there had been attempts to name the community, but none of them stuck. Some residents wanted to call the area Denby after the nearby, now-shuttered Denby High School. Evans says that the connective tissue for neighbors, the schools, was lost when the city shuttered the doors on many of them as its public school system struggled under state control. A concerted organizing effort was initiated a few years back to name the area, with the Detroit Future City group spearheading the initiative. They eventually came up with North East Area

Is there anxiety over not having a well-named neighborhood with precise boundaries? Yes and no. There is a risk erasure for not having a precise definition, but it’s more of a down-the-road issue. It ranks low in the hierarchy of needs for neighborhoods battling social and economic ills. Still, people have deep roots in the neighborhoods they live in, named or unnamed. Ultimately though, for Bell and others, neighborhood naming has to have some utility for it to confer any type of lasting meaning.

"There has to be a purpose," Evans says. "There has to be a goal, and there has to be a benefit. If we're just naming the neighborhood just to name it, then people are not going to take all that time to do that, going back and forth, debating. Once we identify our name and what our borders are going to be, what's next?"

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.