Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

From the original story about Michigan's lead exposure problem in Bridge magazine

Just a hint: If you're illustrating a story about lead exposure primarily due to paint chips, this might be a good image to lead with, not a crying Flint child being tested for lead.

There's an old saying that "journalism isn't the art of being understood; it's the art of not being misunderstood."

That's why journalists focus like a laser-beam on the "lede" of a story: That's the first paragraph or first couple paragraphs that frame what the story is about, and why we should care. Since many readers will just scan the beginning of a story and perhaps move on, it's vital to state things clearly up front, so that nobody leaves a story misunderstanding what it's about, or what's at stake.

A case in point might be the recent piece that originally appeared in Bridge magazine that was reprinted, with a few tweaks, in the Detroit News.

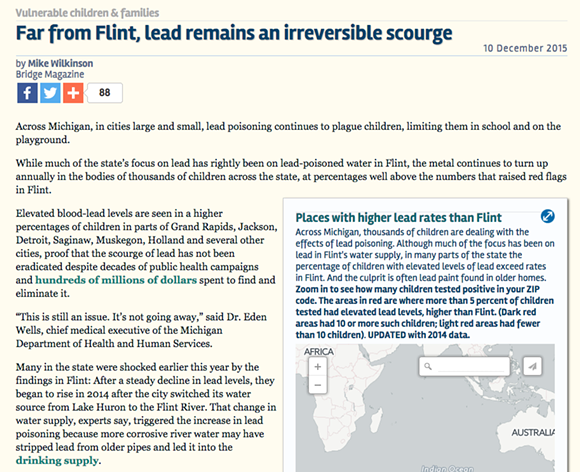

To be clear, and to keep this point up top in this blog post: The original piece by Mike Wilkinson, as it appears in Bridge magazine and online, is a very good story. It uses journalism and compelling graphics to clearly tell the story of how lead poisoning in children remains an issue not just in Flint, but all across Michigan. With the focus suddenly on childhood lead poisoning, it's an excellent time to discuss this.

Wilkinson's story, however, is not primarily about lead in city tap water. It's a study of lead poisoning from other causes: lead paint used in homes and buildings before 1978, lead from exhaust before it was removed from gasoline, among other sources. The only mention of water is in reference to Flint.

A few significant changes appear in the story as it was run by the Detroit News today.

First, the headline is different. The headline for the Bridge piece, at least as it appears online, is "Far from Flint, lead remains an irreversible scourge." In other words, the headline telegraphs that there is nothing new to the lead problem outstate, as it's a persistent (yet diminishing) problem, related to long-term environmental effects.

The News' headline is a little different. It reads (again online): "Kids' lead levels high in many Michigan cities." The distinction implied in the original headline, of a problem that predates Flint, is lost.

The other significant change to the draft the News ran is the treatment given to the original piece's graphics. The original Bridge article leads with a map, and its caption clarifies the distinction between lead poisoning from dirt and paint and other sources and lead-poisoned city water. It says "the culprit is often lead paint found in older homes," which is in smooth accord with the rest of the story. It also shows an image of chipping paint, which is what the story is really about.

The News draft of the story dispenses with the image of chipping paint, and offers plenty of detailed maps of local areas, without the clarifying caption. Readers have to click on a link to get the caption. For the casual reader, this has the effect of burying this vital distinction 14 line breaks into the story. Instead of showing an image of chipping paint, the caption related to paint is run under a photograph of the Flint River.

When posting the story on the News' Facebook page, the status update read: "While much of the state’s focus on lead has rightly been on poisoned water in Flint, the metal continues to turn up annually in the bodies of thousands of children across the state, at percentages well above the numbers that raised red flags in Flint."

Well, this may seem patently obvious, but lead exposure due to lead paint in homes and in soil is something that parents have some amount of control over.

What has drawn anger and outrage about the Flint water crisis is that a state-appointed emergency manager made decisions that ensured the tap water running into Flint's homes, businesses, and public buildings was contaminated with lead. And then the state tried to keep a lid on the problem.

(Just as an aside, childhood victims of lead poisoning and savings-happy emergency managers all do have one thing in common: poverty. Lead abatement is expensive, and poor families have little recourse to lead ... although more than residents whose city has had emergency managers sicced on it.)

Now, far be it from us to accuse the Detroit News of taking a story about lead paint and lead pollution in the environment and repackaging it in such a way that it conflates that important issue with that of the way Flint's residents were drinking contaminated tap water. They clearly would do no such thing, as it would endanger their credibility, given their editorial board's years-long romance with Gov. Snyder and emergency management. We're guessing they would definitely not be OK if people were to scan the story for a moment, read a few paragraphs, and then come away thinking that the Flint crisis may be overblown. The last thing the Detroit News editorial board wants them to think is, "After all, lots of Michigan cities have high levels of lead in their water."

But, just for a little refresher course in journalism, we'd urge them to take a look at the way other news outlets put the distinction right up front where it can be noticed by the casual reader. See how this works?