News Hits has concluded that, when it comes to politics, money is a lot like water. Laws can be created to reduce the corrupting and disproportionate influence those with deep pockets have on the process, but cash still has a way of finding its way into the hands of politicians. It’s like trying to dam a river: It may work for a while, but eventually the water is going to continue to find its way downstream.

These aquapolitical musings were prompted by a new report issued by the Public Research Group in Michigan (PIRGIM), a nonprofit band of do-gooders based in Ann Arbor. Titled Undermining Democracy: Michigan’s Failure to Limit Contributions to PACs, the report discusses how political action committees are being used to skirt campaign contribution limits. In Michigan, individuals are limited to contributing between $500 and $3,400 (depending on the office) to any one candidate during an election cycle, but there is no limit to the amount of money someone can give to PACs, which are allowed to contribute 10 times the individual maximum to candidates.

Astute readers have already grasped the problem. By setting up and funding a PAC, rich folk can funnel as much as $34,000 into the pockets of a favored pol. The result, notes the executive summary of the report (see it online at www.pirgim.org) is that the wealthy are able to “further aggregate their political power, pushing the views of less-wealthy citizens further to the margins.”

The report notes that there are nearly 1,000 PACs in Michigan, and that in the 2002 election cycle the top 150 raised nearly $33 million. That amounts to more than all the money candidates for the state Legislature raised during the same time frame.

The report notes that there are good PACs, those funded by small contributions from lots of people that serve legitimate democratic purposes. It’s those dominated by a few very wealthy individuals that raise concern.

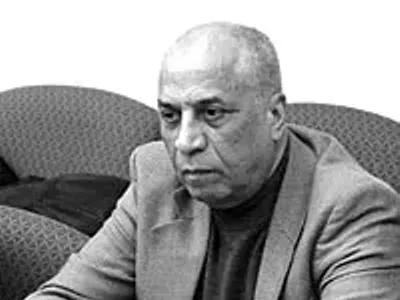

One of the most egregious examples of this sort of influence peddling can be found in a PAC flush with cash from Detroit businessman Anthony Soave, who made a mint in the garbage business before branching out into metal recycling, insurance, hydroponics farming and other ventures. The PAC is called Citizens for Michigan, but if there were a truth in PAC-naming law, it would rightly be called Citizen for Michigan. Soave, the CEO of Soave Enterprises, contributed $210,000, or nearly 90 percent of the PAC’s total take, for the 2002 election cycle, according to the PIRGIM report. Twenty-two of the PAC’s 29 contributors gave just $1. With the exception of Soave, none gave more than $5,000.

To rectify the situation, “PIRGIM recommends placing a cap on the amount individuals contribute to PACs, and reducing the amount PACs can give to pols.

“Ending the system under which a small number of individuals can channel vast sums of money into politics and lessen the electoral influence of ordinary citizens is important to ensuring all citizens are equally represented in political decisions,” assert the report’s authors.

But no one expects that to happen soon.

“We are a long way from politicians wanting to address this problem,” says Brian Imus, PIRGIM’s state director. The public needs to be aware wealthy special interests can use this as a way to get around individual contribution limits.

PIRGIM’s proposals are certainly worthy, but unless the public rises up en masse and demands the changes, chances are good that water will start flowing uphill before our legislature acts to reduce such a lucrative funding gusher.

Contact News Hits at 313-202-8004 or [email protected]