Nora Rodriguez hesitates before opening the gate to the front yard of a home on Detroit’s Southwest side after noticing the bold orange letters of a “Beware of Dog” sign on the house’s front porch.

“Dogs are one of the obstacles in this community,” Rodriguez says. “This is why it’s better or faster to canvass in groups of two, that way if a dog chases you the other can kick it in the leg or something — I don’t know.”

Rodriguez is a canvasser with Congress of Communities, one of the organizations hired by the city of Detroit for a door-knocking campaign to encourage residents to get vaccinated for COVID-19.

Rodriguez grew up in Southwest Detroit and has experience canvassing in the community, she says. She also participated in the campaign to boost Census participation in 2020, an operation that transformed into the door-knocking campaign after Detroit received $1 million in FEMA funds to help curb low turnout rates for COVID-19 vaccinations in the city.

Both the tactics and infrastructure from the 2020 Census campaign have been redeployed for the door-to-door vaccination campaign, according to Victoria Kovari, executive assistant to Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan, who was in charge of the Census campaign and is now overseeing the campaign to boost vaccination rates. These efforts include door-to-door outreach, incentive programs, direct texting and mailing for apartments where canvassers can’t gain access, and the purchasing billboards along Detroit highways with information on where to get vaccinated, Kovari says.

As to whether the campaign to encourage COVID-19 vaccinations will be more successful than the campaign to drive up census participation remains to be seen.

As Rodriguez makes her rounds canvassing around Hubbard Farms Wednesday afternoon, many if not most of the residents at the houses she visited don't answer the door. In these instances, there was nothing to be done but leave an informational packet on the doorknob, before marking the house as “not home” on an app designed by ArcGIS, to help Detroit canvassers share areas they’ve covered and to help the city collect data on participation rates.

When Rodriguez does interact with people in the neighborhood, many are older residents who had already been vaccinated.

Manuel Gonzales, 50, was sitting on his porch when Rodriguez approaches to ask if he had been vaccinated.

“The shots, both shots? No, I haven’t gotten them,” Gonzales tells Rodriguez.

Gonzales's skepticism was rooted in the idea that the vaccine shot would potentially make him ill. He told Rodriguez his mother and stepfather had recently received the vaccine and that they had experienced symptoms like cold sweats and “the shakes” afterward. He was worried he would have the same side effects and was hesitant to get the vaccine because of it, he says. Among his other concerns was the recent pullback of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine after state authorities halted its use out of concern that it was linked to cases of blood clotting, but the vaccines were quickly reauthorized for use after the blood clotting was found to be linked to a small number of women.

Gonzalez also tells Rodriguez that his friend was also hesitant to get the vaccine, but for different reasons.

“He wants to get it but he’s worried about the cost and he doesn’t have his papers,” Gonzalez says, alluding to his neighbor's immigration status.

“No, it’s free,” Rodriguez tells him. “The shots are free, and all you need is some kind of identification, even something outdated or like a bill for utilities from the city or something like that.”

After the interaction, Gonzalez says he would likely get the shot at some point, but for an incentive not linked to those offered by the city; namely that he was worried you would need to show a vaccination card to get a “good job.”

The conversation highlighted some of the unique issues around vaccine hesitation for residents in Southwest Detroit, Rodriguez says, adding that not all of it is rooted in conspiracy theories but more reasonable skepticism.

Rodriguez says she hasn’t experienced anyone who was outright hostile to her because of her advocacy for the vaccine because of its politicization in the media, but she understood it might come up.

“I’m not here to debate anyone,” Rodriguez says. “Everybody has different opinions around the vaccine, I’m just here to give them the information they need that’ll help them get it when they want it.”

Kovari says she’s hopeful that the campaign will drive up vaccination participation in Detroit neighborhoods, but was hesitant to put an exact number on what would make the program a “success.”

“I don't want to put out an arbitrary number on it, but a 20% increase in these areas would be significant for us,” Kovari says. “If we get 170 people make appointments right then and there, that’s good. I mean, that's potentially 170 people who are not going to get infected, pretty much. We’ve done just under 20,000 doors so far, mostly around Northwest activity center, Farwell, and Samaritan hospital, and we’re looking at those places, in particular, to see if walk-in traffic around there is picking up.”

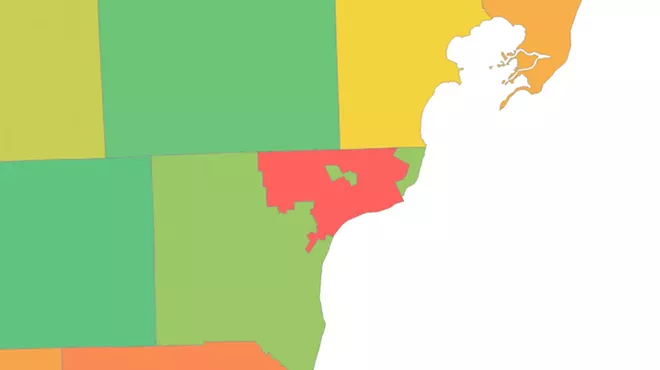

Michigan’s vaccination rate currently sits at 52%, just shy of the 60% to 65% threshold officials say would allow the state to lift some of the capacity limits on public gatherings. The city of Detroit’s current vaccination rate is 33%, well below the rates of many of its surrounding suburbs, according to the State of Michigan’s COVID-19 vaccine dashboard.

For Rodriguez, the overall vaccination numbers are not as important as the well-being and protection of individuals in her community. Rodriguez says that she has asthma, a condition that she says likely originated because of air pollution in Southwest Detroit, and can make a COVID-19 respiratory infection more dangerous for those who contract it.

“There is a lot of air pollution here and I do think that’s one of the reasons I do have asthma, it’s something that affects a lot of the community here,” Rodriguez says. “So yeah, I definitely believe that, but that’s one of the reasons people like me try to, you know, let other people in my community and all over the place know about those programs available for them. That way they don’t feel like they’re alone or don’t have anything to help them out.”