Photo courtesy Shutterstock

Explosion of the USS Shaw's forward magazine during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941.

Seventy-five years ago today, the Empire of Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in a sneak attack that brought the United States into World War II.

It’s a momentous bit of history, but resonates in Detroit more loudly than other places. Almost overnight, it changed the tempo and mood of the city. It attracted hundreds of thousands of people with the war work that ended the Great Depression. It touched off struggles over who gets to lay claim to Detroit that echo to this day.

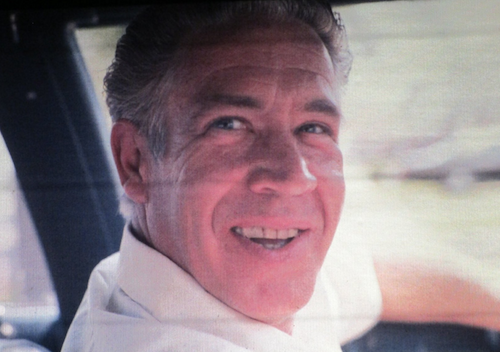

But for my dad, then an 11-year-old kid growing up in Dearborn, it was an ordinary Sunday. He did what he did practically every Sunday: Walk for an hour across town to the Calvin Theatre, sit through the newsreels, the serials, the cartoons, the B-picture, and the main attraction. Who knows where he got the money for admission, scrounging and saving it during the Great Depression. Sometimes he’d watch the whole program over again. If he had enough money, he’d do it Saturday and Sunday.

But when he walked out of the Calvin that Sunday afternoon, the scene was much different from the way it was when he’d arrived at the movies. The traffic out on Michigan Avenue was pretty much stopped. People milled in the street, listening to the radio. Pop gave me the sense that a lot of them were mad as hell, even taking pots and pans and using them as crude gongs to create a din.

During my childhood, it was unusual to have a father who even remembered that day. My parents got together later in life, and most of my peers had parents who were born after the war. It was a mixed bag having an older father. The generational gulf was massive. He grew up during hard times, never having breakfast and having to put fresh cardboard in the bottom of his hand-me-down shoes every morning. He grew up rough around the edges, and his humor had a vulgar streak a mile wide.

He was no dummy, though. What he lacked in gentility he made up for with intelligence.

I made the error one time of asking Pop if he was in World War II. He laughed and roared at me, “What? As a waterboy?”

But he certainly was involved in the war. His family were all war workers, producing war materiel to defeat Imperial Japan and the fascists in Europe. It was the big story of his late childhood and early teenage years. It filled the newspapers, poured out of the radio, thundered during the newsreels, and was the source of the drama in so many of the films he trooped across town to watch every weekend.

Fascism was no joke to Pop. Fascists were criminals who won political power, they were murderous gangsters who needed to be destroyed. They didn’t get cutesy names. They didn’t get the benefit of the doubt. The war was being fought so we could get over to Berlin and to Rome and see those sons-of-bitches hanged.

In this way, Pop came of age during the great golden age of leftism. The Great Depression had thoroughly discredited the banks and big business. The labor unions had finally unionized the large industrial concerns. And the president, though still a capitalist, was easing the country into the kind of socialistic mixed economy my dad’s generation never questioned. And fascism, especially Adolf Hitler, were the enemy. The goal was to destroy fascists and put them in prison — if not the cemetery first.

Back before sneering flame-war artists began waving “Godwin’s Law” in the face of anybody making a comparison to fascism, Americans had been pretty free about comparing people they distrusted to Hitler. And why not? Every time they saw intrusive government bureaucrats, cynical big business interests, and spit-shined military phonies, they’d remember they just spent four long years fighting those bastards when they spoke German. Why not when they spoke fine English?

Pop wasn’t a perfect person. He’d never have won father of the year. But to him, fascism wasn’t a hypothetical thing. It was a fact of living history. Maybe today people can try to beautify it, to call it the “alt-right” or “post-truth” or some other hyphenated appellation. Maybe they can claim that comparing homegrown extremists to Hitler is bad debate etiquette. I doubt Pop would have cared much.

He only said it once, and I think he’d been drinking, but when I was a boy he drew me close and told me squarely: “When you see people goose-stepping in your front yard, there are only two things you can do: You can join them, or you can kick their asses.”

I always got the sense that he respected the latter choice more.

“When you see people goose-stepping in your front yard, there are only two things you can do: You can join them, or you can kick their asses.”