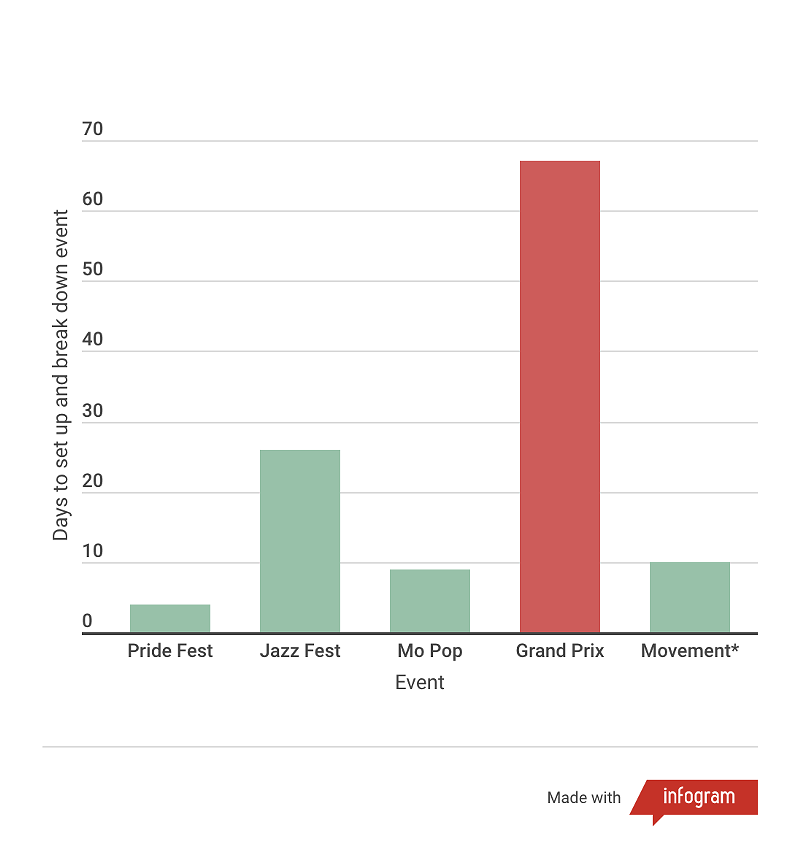

The Grand Prix's construction takes a lot longer than Detroit's other major events

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Spring and summer are a time when Detroit hosts world class concerts, festivals, and other events that draw visitors from all over the world.

Detroiters barely notice the setup and breakdown for most events, but construction for one takes much longer and causes a bigger headache than the others — the Detroit Belle Isle Grand Prix.

Pride Fest, Jazz Fest, Mo Pop, Movement, and all other Detroit events big and small are largely up and down in a matter of days. During their setup, access to public spaces isn't cut off for long periods, if at all. There are no road closures, no traffic jams, and no desecration of the area around the event. Pedestrians and cyclists aren't put in any danger, and the events generally respect the city and people around it.

Contrast that with the Grand Prix, which takes over 60 days to set up and breakdown, and much longer if one includes remediation of damaged park grounds. During the Grand Prix's construction, some of the park's best areas are turned into heavy construction zones that are off limits to the public. The island is desecrated by miles of concrete barriers, grandstands, construction barrels, trucks, billboards, fencing, and so on. The streets are narrowed, creating a dangerous situation for pedestrians, cyclists, and motorists. The entire operation is disrespectful to the city and residents.

Of course, the Grand Prix's footprint is larger so it's reasonable to assume that it will take longer to build out. That's true, but the level of disruption needs to be factored in when asking the question, "Is this event worth it?"

The Grand Prix's construction period is also among the longest of any street race in the world. We checked and found other race organizers are mostly much more efficient than Detroit Grand Prix founder Roger Penske's crew. For example, the Toronto Honda Indy, which takes place in downtown Toronto, is up and down in about two weeks with no road closures except for race day.

Race organizers have also pointed to the Grand Prix's alleged economic impact. But we spoke with multiple economists who explained why the Grand Prix's estimates are wild exaggerations, and the economic benefit is likely much less than what organizers claim.

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources last year agreed to allow the race to run on Belle Isle through 2021, with the option to extend through 2023.

That contract was signed under previous DNR leadership that was installed by former Gov. Rick Snyder. Metro Times requested an interview with new DNR director Daniel Eichenger, but that request was denied. A DNR spokesperson said Eichenger wouldn't give an interview because Metro Times wrote stories about the controversy around the race (It's worth noting the controversy has been well-documented by nearly every local outlet and several national publications.)

"Given your past reporting on this subject, I don’t have any expectation that your interview would be a fair account of this issue," DNR spokesperson Ed Golder wrote in an email.

In an effort to present all points of view for this story, we asked Golder and Eichenger to comment. They did not respond to the request.

*Estimate of Movement's construction period.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.