By 2009, McNally decided he'd had enough parole hearings to last a lifetime. No more, he told his case manager. Each previous hearing — about a half-dozen throughout the last three decades — had ended with the parole board restating the obvious: McNally's past crimes made him a risk to the public.

But after a miscommunication with a case manager, McNally was nevertheless roused on the morning of July 18, 2009, and told he was expected at a parole hearing the next day. The inmate grumbled, but an order was an order.

The meeting seemed normal enough. The board quizzed him about his record and his activities in prison. By now, McNally had collected about 30 years of generally good behavior. Like Trapnell, McNally had been affected by the 1978 caper and its sobering aftermath. He wrote to his mother about changing her will. "Don't leave me anything," he told her. "I'm never going to get out of prison."

Yet McNally left the parole hearing in a state of dumbfounded bliss, and he walked back to his cell, grinning ear to ear. Against all expectations, he'd been given a release date. The board had evaluated his 37 years in prison and deemed him capable of handling parole.

Six months later, on Jan. 27, 2010, McNally walked out of the federal prison in Atwater, California, and hopped on a Greyhound bus. He initially requested to be settled in Tennessee to live with an old prison buddy, but that plan had been denied. McNally had no interest in returning to his estranged family in Michigan.

So McNally bought a ticket to St. Louis, the scene of his 1972 hijacking.

"I had no intentions, really, of staying in St. Louis," he says. "I had planned to go on the lam, rip off some banks, get the vaults, get all the money, so forth and so on."

On the long bus ride, he split his attention between looking out the windows and the fact that people on the bus were making phone calls by holding plastic rectangles to their ears.

Yet he somehow never got around to riding off into the sunset as a bank robber. Instead, he found he quite enjoys civilian life. With the aid of a reentry program affiliated with the Archdiocese of St. Louis, he was placed in the south city apartment where he resides to this day, paying his own rent and caring for a fluctuating number of cats. He watches a lot of Netflix, especially true crime shows that sometimes feature his old prison acquaintances.

These days, McNally is still reconciling his law-abiding life with the conman who resides in his heart. He's been burned multiple times on get-rich-quick schemes, from buying penny stocks to chasing fictitious fortunes promised by email scammers. His attempts to open wholesale businesses selling jewelry, knives, and wristwatches each folded in quick succession. And although he purchased 1,000 lottery tickets before the drawing date, McNally failed to win a $1.6 billion Powerball jackpot in 2016.

On a summer afternoon, a rickety air conditioning unit rattles in the window of McNally's second-floor apartment as the old hijacker pads his way to a desk in his living room.

"Check this out," he says, and retrieves a shiny metal sphere, about two inches in diameter. He holds it up to his eye.

"It thought it was a ball bearing, for big machinery, but there's a bell inside of it," McNally says. He shakes the bauble for a few seconds, producing a mad chorus of jingles. "I don't know what it is," he laughs, "but when I saw that, I said I got to have it."

This is not the existence McNally envisioned for himself as he clung to the stairwell of a Boeing 727 all those years ago. He risked it all, experienced an amazing adventure, and in the process lost everything. Once, he had dreamed of riches. Now, the fact that his kitchen is stocked with groceries and beer seems like a miracle.

"I've come further than most people would reach," he says. "I never thought I would get out of prison. Very few people have had my opportunity."

McNally drags on a cigar. He says he wants to "rehabilitate" the memory of Barbara Oswald, a woman whose only crime, in his mind, was wanting a better life for herself. She too had risked everything.

"It's tragic," McNally says. "That woman was driven to her death, just because some phony monsters were intent on getting out of prison under any circumstances."

And now, McNally is the only monster left. Trapnell died alone and incarcerated. Kenny Johnson, the third member of the 1978 escape team, also died in prison more than 10 years ago. Allen Barklage, the hero pilot who foiled their escape, died in a helicopter crash in 1993.

"There's nobody else," McNally says. "I'm the last of the people who know the facts."

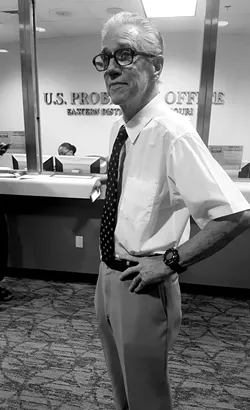

After what McNally believed was an ill-fated meeting with his parole supervisor, there was nothing to do but go back to his life on parole, complete with random inspections, restrictions on his movements, and the looming possibility that, any day, a single misstep could land him back in prison again.

"The nature of this crime" — the parole officer's testimony echoed in McNally's mind. The meeting had seemed to confirm his beliefs about the criminal justice system, those lessons he'd learned in a series of courtrooms and, later, at the hands of prison guards: Justice was a thing you had to take, by physical force or legal fight, not something granted by a board of bureaucrats. McNally had even begun the process of handwriting a lawsuit targeting the federal parole commission and his parole officer, whom he planned to accuse of violating his rights and conspiring illegally to keep him on parole. Never mind if it was true. When the law bites you, you bite back.

McNally's good fortune, however, knocks on his apartment door on the afternoon of Oct. 4. Shirtless and wearing a worn pair of jeans, McNally welcomes in his parole officer, the very same guy who broke his heart at the August hearing.

But this is no regular checkup.

The parole officer, Tim, hands McNally a single sheet of paper.

"I have some good news," Tim says. "You're off parole."

McNally's face breaks into a smile.

"Oh no," he jokes. "I'm disappointed. I need to have you come over here at least once a month, I need to see you. I don't get enough visitors." The two men laugh, and after a few more pleasantries, Tim leaves McNally to consider his future.

It's a heady feeling, freedom. McNally can travel whenever the mood strikes. He can live anywhere and associate with anyone if he wants to. Or he can remain in St. Louis, playing with his cats and reliving memories of crimes past.

McNally hasn't set foot on a plane since 1972. Even now, he's too paranoid about homeland security agents and terrorist watch lists to actually buy a ticket. But if you find yourself in Lambert airport, you may spot a thin, white-haired man with a light smirk on his face, watching the security lines and rows of shoeless travelers hefting suitcases through metal detectors.

Someday, Martin McNally allows, he just might fly again.

A version of this story originally ran in St. Louis' Riverfront Times. It is republished here with permission.