When the red-and-white helicopter made its first pass south, several thousand feet above the prison, McNally signaled to Trapnell and Johnson that they should get ready to run.

Minutes later, the muffled thump of rotors became a sharp whine as the helicopter crested the treetops south of the prison. Guards were already scrambling to arm themselves, and the three inmates had just moments to take advantage of the confusion.

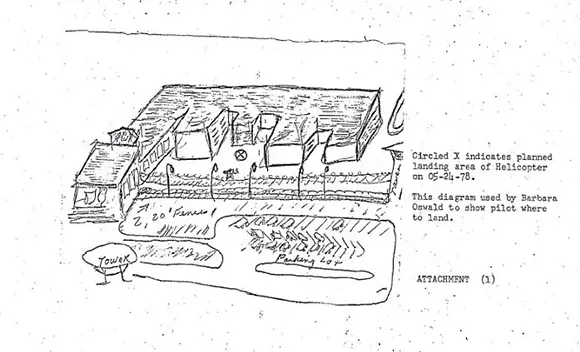

Trapnell, McNally, and Johnson made their move, dashing to a restricted area between two housing units, coming to a yard just big enough for a helicopter to land. Trapnell laid out a bright gold jacket to catch the pilot's eye, while McNally jumped and waved his arms as the helicopter tilted and wobbled above the prison.

But instead of landing in the yard, the helicopter settled next to the prison's administration building, located behind several layers of fencing. The whine of the rotors abruptly fell silent, and a thin figure in a blue flight suit leapt from the pilot-side door. There was no sign of Oswald.

Something had gone terribly wrong, but there was no time to figure out what. Trapnell lay down in the grass, seemingly catatonic and unresponsive to McNally's urging — to run the hell out of there.

McNally and Johnson attempted to flee the scene, sneak over a roof, and slip back into the recreation yard, hoping to disappear into the mass of hooting prisoners watching the commotion. However, by now every guard was on high alert, either rushing to the helicopter or searching the prison grounds for potential escapees.

Minutes later, McNally and Johnson were spotted on the prison building's roof and apprehended.

Trapnell, the escape's mastermind, didn't move an inch from where he'd collapsed in the yard. A guard later reported that upon discovering the prone inmate, he told Trapnell that he'd been lucky. "You would have been blown away," the guard said.

"I knew it was a set-up," Trapnell spat back. "Was that their helicopter, or mine?"

Inside the helicopter, Oswald's body lay slumped against the cabin's rear seat. She had been shot in head, spattering blood throughout the cabin and across the helicopter's doors. Bullets had smashed a ragged hole through the side passenger window.

In her final hours, Oswald had tried her best to fulfill her lover's instructions.

She'd reserved the helicopter several days prior, and called the charter company's office around noon to confirm her flight with pilot Allen Barklage. Oswald had posed as a St. Louis businesswoman curious about the condition of some flooded properties in Cape Girardeau. With Oswald in the rear passenger seat, Barklage took off from a downtown St. Louis heliport around 5:30 p.m.

After 30 minutes of flying, Oswald tore off Barklage's headset and put a gun to the pilot's temple. Barklage tried to talk her out of it, but she was adamant: She ordered him to fly east, following a chart to the location where they would rescue three inmates being housed at the U.S. Penitentiary in Marion.

But as Barklage made his first pass over the prison at 5,000 feet, he noted the imposing towers and armed guards. A Vietnam veteran and former combat pilot, he considered the likely possibility that those guards would shoot an escaping helicopter out of the sky. He had no intention of dying that day.

As Barklage brought the helicopter around again for the second and final pass over the prison, he informed Oswald that helicopter doors were difficult to handle, and she was better off opening them now to save time. As Oswald struggled with door, she shifted the gun to her right hand and took her finger off the trigger.

Seeing his chance, Barklage took his hands off the controls and snatched at Oswald's pistol. The two struggled as the unpiloted craft pitched sickeningly through the air above the prison yard. According to Barklage, the fight lasted only 10 or 15 seconds.

When he'd finally wrested the pistol from her grip, Barklage later testified, Oswald had reached for a bag beneath her seat. She told him, "It doesn't make a difference. I've got another one here."

Barklage pulled the trigger four times, spraying broken glass and blood inside the cabin. Oswald fell back, motionless, and Barklage regained control of the wildly pitching helicopter.

When armed guards approached Barklage on the ground, the pilot was nearly incoherent. "I killed her," Barklage ranted, one guard would later report.

"I have been hijacked," Barklage said, over and over. "I have killed and we need an ambulance."

Trapnell and McNally weren't finished with the Oswald family.

The daring escape attempt had drawn national news coverage, and there seemed little doubt that the inmates would be hit with harsh sentences. But as the failed escape crew prepared their defenses — each faced charges for attempted escape, air piracy, and kidnapping — Trapnell once again demonstrated his skill for undermining the legal system.

Trapnell represented himself in court, and in so doing, received privileges reserved for attorneys. For one, he was able to arrange unsupervised interviews with defense witnesses. One of those witnesses was Barbara's grieving 16-year-old daughter, Robin.

The death of her mother had left Robin depressed and at the point of suicide, details she confided to Trapnell.

"I felt sorry for Robin," Trapnell recalled years later during an interview for a short-lived '90s crime anthology series, FBI: The Untold Stories. "The things she was telling me, I felt a responsibility. I was the one who caused her mother's death. At the same time, I wanted to get out of prison."

Trapnell came to McNally with a new plan: He had seduced Robin, and now the teenager had agreed to finish the job her mother started. Robin would hijack a plane and demand Trapnell's release. As before, Trapnell promised McNally could come along for the ride.

Just days before the trial's conclusion, Kenny Johnson, the third escapee, pleaded guilty to lesser charges for attempted escape. McNally and Trapnell felt no such compunction, and the two arrived in good spirits to the verdict hearing in St. Louis on Dec. 21, 1978.

Trapnell had gotten word to Robin Oswald the night before: She would hijack a TWA flight out of Louisville on its way to Kansas City. In her purse, she'd smuggle a roll of duct tape, some wires, and three railroad flares.

It was McNally who'd insisted Robin be outfitted with a fake bomb. She was unstable, he told Trapnell, and he didn't trust her to handle a pistol, let alone an explosive that could take down a plane full of people. Trapnell agreed.

It was 10 a.m. when Robin, seated in the back of the flight on its way to Kansas City, announced the hijacking and rerouted the plane to Williamson County Airport near Marion. A passenger later reported that her demands amounted to a simple, repeated statement: "I want Garrett."

The judge presiding over Trapnell and McNally's trial ordered the jury immediately sequestered, to keep them away from TVs and radios blaring the prejudicial news updates. But Robin Oswald's hijacking attempt only put a temporary stop to the proceedings in St. Louis. After a lunch break, McNally and Trapnell chain-smoked in a holding cell, fully expecting to be called any minute to Williamson County Airport.

The call never came. After nine hours, Robin Oswald surrendered to FBI agents, who recovered the fake bomb and took her into custody.

That evening, a jury returned identical verdicts against McNally and Trapnell: guilty on all counts.

McNally was given another life sentence for air piracy, 75 years for kidnapping, and five years each on charges of attempted escape and conspiracy. The years were added consecutively to his life sentence from 1973. After the conviction, McNally's release date was set for the distant year of 2082.

But McNally had escape skills of his own. Arguing on appeal, McNally and his lawyers raised the issue of news reports covering Johnson's guilty plea before the trial. Surely coverage had prejudiced the jury against McNally and Trapnell.

In 1980, the U.S. Court of Appeals issued a decision that went even further than McNally had hoped. Not only did the judges rule that the trial court erred in not properly examining jury members for bias related to the news reports of Johnson's guilty plea, but the appellate panel actually acquitted McNally on two of the most serious charges — air piracy and kidnapping. Although there was ample evidence to prove McNally's participation in the escape plot, the judges wrote, nothing tangible linked him directly to Barbara Oswald, the plan to hijack the helicopter, or the kidnapping of Allen Barklage.

For her part in attempting to free Trapnell and McNally, Robin Oswald was tried as a juvenile and reportedly released after a short sentence. Considering Trapnell was already facing more than a century of jail time for his previous hijacking and bank robberies, prosecutors chose not to charge him for manipulating the teen girl.

Trapnell would never again attempt an escape. In 1993, he died behind bars of smoking-related emphysema.

McNally had no reason to expect a different fate. By the dawn of the 21st century, he'd given up hope of appealing his 1973 conviction for air piracy or reversing his life sentence. He wasn't a fighter anymore, just an old con moving through a series of concrete rooms and hard beds.

McNally resigned himself to the inevitable. He waited for death.