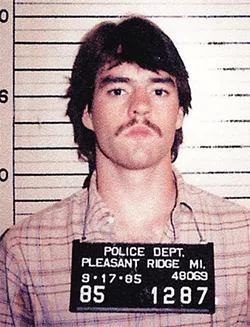

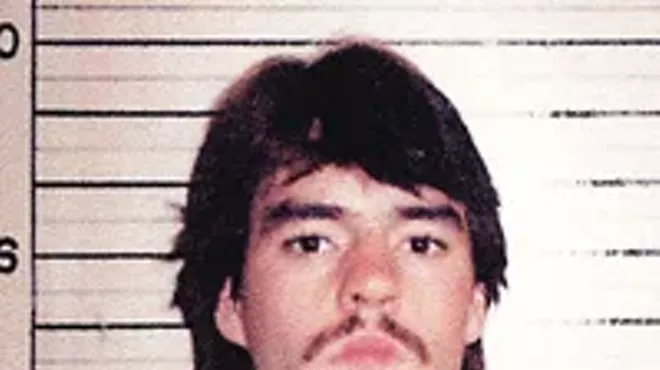

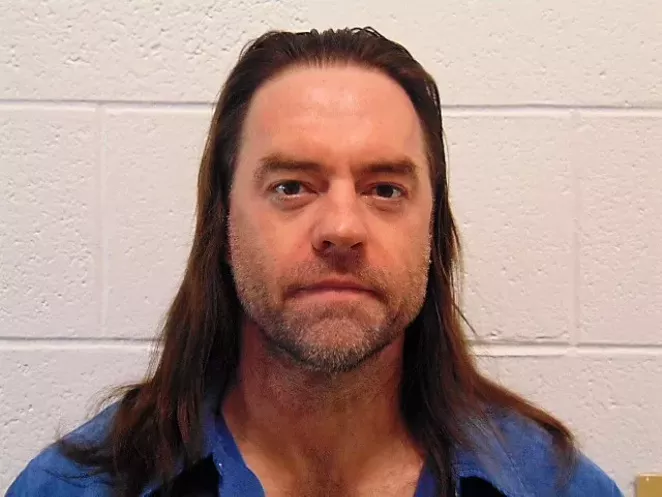

His pleasant greeting and upbeat energy during an afternoon chat give no hint of a future that involves dying in prison. In fact, the inmate formerly known as Fredrick Freeman answers a telephone call to the conference room where he has been escorted in a manner more resembling a staff member than an accused killer.

"Macomb Correctional Facility, Temujin Kensu speaking," he announces, using the Buddhist name he adapted decades ago.

In one sense, it's perhaps fitting that Kensu, who observed his 59th birthday a little more than a week earlier, comes across as serene and composed, given the 36 years during which he has mentally adjusted to his environment. But for the next 60 minutes of conversation, Kensu, who is believed by a diverse, internationally scattered core of supporters to be wrongfully convicted for the 1986 murder of Scott Macklem, expounds on the difference between adjusting to loss of freedom and accepting it. What his lawyers and strongest advocates thought just might be his last hope of exoneration was shattered in early May when the State of Michigan's Conviction Integrity Unit rejected his petition.

"I try to keep my head up and stay positive," says Kensu. "I have an amazing group of people behind me and that helps keep me going."

The "amazing group" he describes has included a wide array of credentialed and well-regarded public officials and private citizens, ranging from a current Michigan Supreme Court justice, a former Michigan Supreme Court justice, a former FBI agent, a retired police detective, state and federal lawmakers, and multiple private investigators, all who say Kensu was wrongly convicted. He was in bed with his girlfriend at their home near Escanaba, Michigan, at the time of Macklem's fatal shooting about 400 miles away in the St. Clair County Community College parking lot in Port Huron, Kensu insists. But despite multiple alibi witnesses, including the girlfriend who wasn't called to testify, a jailhouse informant and a drug-addicted lawyer were among factors that led to his guilty verdict at age 23. The informant later recanted his story that Kensu had confessed, but Kensu was left to serve a life sentence without parole. His only known connection to Macklem — the son of the mayor of Croswell, a small town northwest of Port Huron — was that they dated the same woman at different times, says Kensu, who passed two polygraphs examining his innocence.

Multiple efforts for relief from the court have failed, despite a ruling by U.S. District Judge Denise Hood in 2007 that Kensu be released or granted a new trial. Among other flaws, she determined that he'd received ineffective assistance by his defense lawyer. But a superior court overturned Hood's ruling, saying Kensu's motion had been filed after the deadline. When a recent request that his sentence be vacated was turned down by the Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU), many of Kensu's supporters were devastated. Instead, the unit closed Kensu's case, citing a lack of "evidence not at all considered at trial or during post-conviction appeals," which he and his advocates say departs from CIU's previous criteria.

"There is nothing that qualifies as new information supporting the factual innocence claim," wrote Valerie Newman, special assistant attorney general with the CIU.

But not only has the CIU's definition of "new" become a subject for debate, in light of Kensu's rejection, he and his legal team argue that the unit never insisted on the court standard as a requirement for exoneration in the first place.

"What happened with the CIU is a tragedy and it has to be called out," Kensu says. "[Attorney General Dana Nessel] has to be called out for this, and I don't mean violence or kicking her out of office, but I mean she has to be held accountable."

Kensu hoped statements from a woman named Beth Stier, who says she spent time with him in the hours before Macklem's death, would satisfy the CIU and they'd fling open the prison gates. While his verified Upper Peninsula location appeared to be Kensu's strongest defense during the trial, a prosecutor spit-balled that Kensu could have chartered a plane, landed in Port Huron, shot Macklem unnoticed by witnesses, and flown back in time to present himself in the community. Stier's account of being with Kensu when his car broke down, and recalling he'd gone nowhere, was shared with CIU. Kensu says he eventually found Stier a ride home, then waited in freezing November temperatures until he found assistance.

"Not only did I never speak to her again after that," he adds, "but she was never called to trial."

Newman's letter, while acknowledging Stier as "the one person ... who is new," later states that her recollection would only be "cumulative" to other testimony initially offered about Kensu's whereabouts and car trouble.

Imran Syed, co-director of the Michigan Innocence Clinic, who has represented Kensu for about 12 years, calls the CIU's response unreasonable and unprecedented since the unit's formation. Requiring evidence not reviewed by a court undermines CIU's expressed purpose of remedying wrongful, court-rendered convictions, says Syed. But the rule applied toward Kensu is even more rigid, he adds.

"If you present any new evidence, the standards used in court ... are that we'll look at your whole case, top to bottom," says Syed. "I know they couldn't have done that, because if they did they would have concluded he was innocent."

"The process for review of cases has been consistent since the creation of the Conviction Integrity Unit," says Amber McCann, communications director for Attorney General Nessel's office. "The unit has so far exonerated four individuals."

B. David Sanders, vice-president of Proving Innocence, a Detroit-area advocacy organization that aids wrongfully convicted prisoners and those exonerated, submitted a written response to Nessel one day after the May 17 decision Newman announced in her letter. "We are aghast and disgusted with the CIU and your decision not to grant justice to a wholly innocent man, Temujin Kensu (a.k.a., Fredrick Freeman)," wrote Sanders. "This is unconscionable and unacceptable, and a betrayal of your claim the CIU would fight for true justice for the wrongfully convicted."

One week later Sanders' feelings were echoed in a joint press release by U.S. Rep. Andy Levin, U.S. Rep. Rashida Tlaib, and state Sen. Stephanie Chang.

"We were deeply disappointed to learn that the Michigan Attorney General's Conviction Integrity Unit, known as the CIU, has declined to pursue the release of Temujin Kensu, an innocent Michigander who has been in prison for more than three decades," the statement read. "Despite no physical evidence connecting him to the murder and several vetted eyewitnesses who place him more than 400 miles away from the scene of the crime, Kensu remains imprisoned."

“It’s the Conviction Integrity Unit, so it should make sure convictions have integrity.”

tweet this

While expressing "great respect" for Nessel and the CIU, the legislators argued that the "standard used by the CIU in its review of the Kensu case predetermined the outcome — to us, the wrong outcome." The trio urged Gov. Gretchen Whitmer to use her executive powers to pardon or commute sentences for Kensu's relief.

Sanders, too, hopes Whitmer will step in, going as far as to suggest Nessel "might even say, 'I couldn't do anything with this case because of the CIU restrictions, but clemency is appropriate.'"

"I don't want to impugn the integrity of the attorney general or the people who do the review, but it's very, very upsetting," adds Sanders. "It's the Conviction Integrity Unit, so it should make sure convictions have integrity."

To say "it's pretty apparent Kensu is innocent," but he can't be granted freedom because his case doesn't fit the rules, is the definition of injustice, Sanders says. While he should be retired following a career as a community planner with the non-profit Metropolitan Affairs Coalition, he was introduced to the Kensu case about 14 years ago and became fully committed. Says Sanders: "I try not to do much else with the Proving Innocence board, because I'm so focused on this."

He and numerous others, including Levin's uncle, the late Sen. Carl Levin, found so many flaws in how the case was tried, such as the unproven airplane theory, that it became impossible to turn a blind eye, Sanders says.

"Would you not think in 35 years, someone would pop up and say, 'I know who flew him' or 'I know who picked him up after the plane landed?'" he asks.

The next move for Kensu, says Syed, could include a 6500 Motion, which is the last legal option available for convicted felons who've exhausted all of their court appeals, or a request that Whitmer release Kensu.

"All options are on the table at this point," Syed says.

Whitmer has turned down earlier requests for Kensu's release, but he hopes he's gained momentum in the weeks since the CIU letdown.

"Nobody has ever seen a case this bad, and that's why it's followed around the world," he says, adding that he receives letters from as far as Ireland and Denmark. "I'm here (at the prison) with a corrections officer who wrote his term paper on me."

A Freedom of Information Act request for Newman's documented personal recommendation, as opposed to the decision she revealed in the letter, was denied, he says.

Years of going through the legal motions and experiencing mental highs and lows have been challenging on multiple levels, particularly as the long-time martial arts enthusiast has begun struggling with health issues, Kensu says.

"You get caught in the gears of the machine and it won't let you go," he says.

He's hopeful, nonetheless, and continues spreading the word about his case and those of others wrongly convicted through a podcast with help from Paula Kensu, his fiancee. Kensu says he's fighting not only for the chance to come home, but even potentially to support the CIU in exonerating others.

"If we don't get this fixed they'll get away with this," Kensu says, "and if they get away with this, there go the hopes of hundreds of people."

This story has been updated with a comment from Attorney General Nessel's office.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, or TikTok.