Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Without a journalist revealing who leaked a CIA operative’s identity, Scooter Libby wouldn’t have been convicted of four counts of perjury, obstruction of justice and lying to investigators.

And aren’t such cases — this one involving the former aide to former Vice President Dick Cheney — a compelling argument against journalists invoking their privilege not to testify?

“I’m concerned that there are clear cases where compelling disclosure outweighs the interest in not doing so,” said U.S. District Judge Avern Cohn, who spoke at a panel Thursday about shield laws. “If you follow what most journalists want, Scooter Libby would have gone scot-free.”

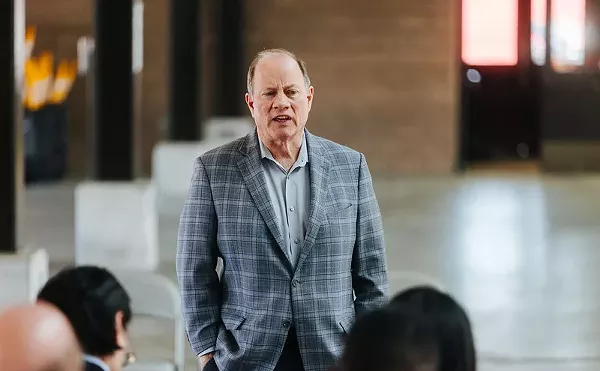

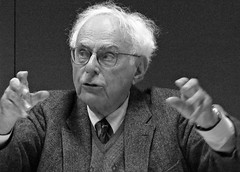

Cohn joined Chief U.S. District Court Judge Gerald Rosen, attorney Herschel Fink, who represents the Detroit Free Press, and Kevin Dietz, WDIV-TV4 investigative reporter, in discussing the shield law issue at the event hosted by the Society of Professional Journalists, Detroit chapter.

In the audience was David Ashenfelter, the Free Press reporter who has twice been ordered to testify about who told him about a U.S. Department of Justice investigation into a former federal prosecutor, Richard Convertino. Convertino is suing the Justice Department alleging his rights guaranteed by the Privacy Act were violated by the leak. Without knowing who gave “Ash” the information that was published in a 2004 article, Convertino can’t win his civil case, his lawyer says.

But Ashenfelter has refused to “give up” any information, arguing recently that his Fifth Amendment rights against self-incrimination could be violated by his testimony because of federal statutes, including the Espionage Act, that “criminalize the improper receipt and distribution of confidential government documents and information.”

Convertino wants him fined for contempt of court for refusing to name name(s); Ashenfelter also could be jailed for contempt as other journalists have been (including New York Times reporter Judith Miller in the Libby case). U.S. District Judge Robert Cleland’s decision is pending.

While 49 states have shield laws on the books, there is no federal statutory protection for journalists. And the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals (the next level up from Detroit’s federal court) is the only federal circuit not to have recognized a journalist’s privilege as a factor in deciding cases like Ashenfelter’s. Cleland cited that lack of recognition in his opinions ordering Ashenfelter’s testimony.

Meanwhile, bills were introduced in both houses of Congress last week that would protect journalists from testifying about their confidential sources in some cases.

“The way I hear it is you’ve got to get a bill through Congress because the 6th Circuit is an outlier,” Cohn quipped.

Before judges order journalists to reveal a source or other information, they first must decide that the information goes to the heart of the matter of the case and that all alternative avenues to obtain the information have been exhausted, Fink says.

But there’s no perfect test to determine a third standard: does the public interest in protecting journalists and their sources outweigh the need for knowing who or where information came from?

“Judges do differ. We don’t have litmus paper: blue you’ve got to talk, red you don’t have to talk,” said Cohn.

“Different judges are going to see that different ways, depending on the particular case and the particular merits the story has,” Rosen said along the same lines.

Without guarantees against the choice of testifying or going to jail, won’t journalists become leery of doing risky stories?

Dietz didn’t think so. “I think almost any journalist would go to jail to protect a source,” Dietz said. “The stories have to be worth it or news is going to continue to get watered down.”

Cohn pointed out courts have found a “continuum of importance” of reporters’ testimony. In criminal cases, journalists may find the fewest shield protections. “The rights of the accused are highest,” he said, noting defendants are entitled to potentially exculpatory evidence that may include journalists’ testimony. If prosecutors are unable to obtain the journalists’ information elsewhere, then testimony may be compelled, Cohn said.

But journalists find the most effective shields in civil suits “ensuring civil litigants a smaller payday,” Cohn said.

Rosen agreed: “If the case is just about money, I’m going to be harder to persuade” to order the testimony, he said.

In the end, as long as journalists are producing stories, confidential sources will be part of them, all the panelists agreed.

“There are some important stories that simply can’t be told without confidential sources who look to journalists to protect them,” Fink says. “The public relies on a free flow of information.”

Both judges said they wouldn’t rule out ever imprisoning reporters, but neither offered an opinion on Ashenfelter’s situation.

Attorney Herschel Fink

Chief U.S. District Court Judge Gerald Rosen

U.S. District Judge Avern Cohn