Detroiters would like to see the eastern edge of downtown be made more walkable, but residents living in the neighborhoods sectioned off by I-375 — the freeway standing in the way of that — say they don't want the sub-level artery turned into a surface street.

Those are the results of a survey that asked more than 300 Detroiters what factors they want the Michigan Department of Transportation to consider as it examines six different proposals for the future of the mile-long freeway stretch. The agency in 2013 announced it was considering reconstructing I-375 for up to $80 million, or spending less to turn it into a boulevard that links downtown with the eastern riverfront and attracts development.

The various proposals are estimated to cost anywhere from $40 - $80 million, with some making room for bike paths, green space and/or new development. Survey respondents were most interested in seeing land used for green space over residential or commercial developments if the freeway is brought to surface-level.

"I hope that the state and city will take these preferences into consideration as the project moves forward, especially because the quality of life, walkability and safety of those living closest to the freeway may be greatly impacted by whatever changes take place,” said State Rep. Stephanie Chang, who conducted the survey with help from her office.

But according to John Norquist, CEO of the Congress for the New Urbanism, a nonprofit that promotes mixed-use, walkable neighborhood development, the poll results should be taken with a grain – or perhaps a whole shaker – of salt.

"I really don't think its an appropriate thing to poll on," he said.

Norquist, who is also the former mayor of Milwaukee, says the public is not equipped with the knowledge to make such decisions. He points to the removal of a 1.2 mile-long elevated freeway in SanFrancisco as an example.

"They took out the Embarcadero Freeway after three referenda – it wasn't until the third referendum that it was approved — and some people thought they would never be able to travel again," he said. "You probably couldn't find one person today who would want that freeway back.

"And they actually had faster trip times after because people were using the grid instead of going all the way down the stretch of freeway and around. But the average person wouldn't know that in a referendum; they just assume all streets should be freeways except the one they live on."

About a third of respondents to the survey conducted by Chang's office live just east of I-375 in Hyde and Lafayette Parks, while about two-thirds of respondents live elsewhere in the city. And indeed, the people living near the freeway had different thoughts on what should be done than their counterparts in the city at large.

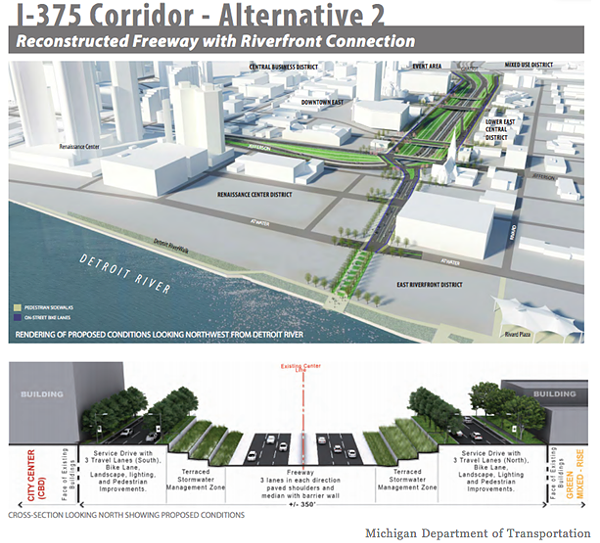

Of six options, survey respondents most often ranked this alternative as their number one choice (27%).

Neighbors surveyed mostly wanted to keep the freeway, likely because it grants them quick and easy access to northern parts of Detroit and the suburbs, but also because it provides a barrier from the hustle and bustle of Greektown and downtown. These Lafayette and Hyde Park dwellers tended to support alternative 2 (shown above), which would keep the freeway but also create a riverfront connection from East Jefferson to Atwater that includes bike lanes and pedestrian improvements. A separate option to keep the freeway and surrounding area exactly as is was also most often among the neighbors' top choices.

But Norquist contends that what's best for the area, and the city of Detroit, is raising the freeway to surface-level and zoning it for mixed-use.

"The purpose of the street is not just getting places, the purpose of the street is for commerce; that's what adds the most value for a city," he says. "In the past, in Detroit, the only thing that mattered was free-flowing traffic, which is why you see so many freeways ... but you don't want to be a city that's great for everyone to drive through quickly and not buy anything."

He says downtown Birmingham is a good example of what the area could someday look like – more quaint than downtown, but still a place for people to go. The stretch of sub-level interstate was built in the 1960's, destroying what was then essentially Detroit's harlem – a community of African-American businesses known as Black Bottom.

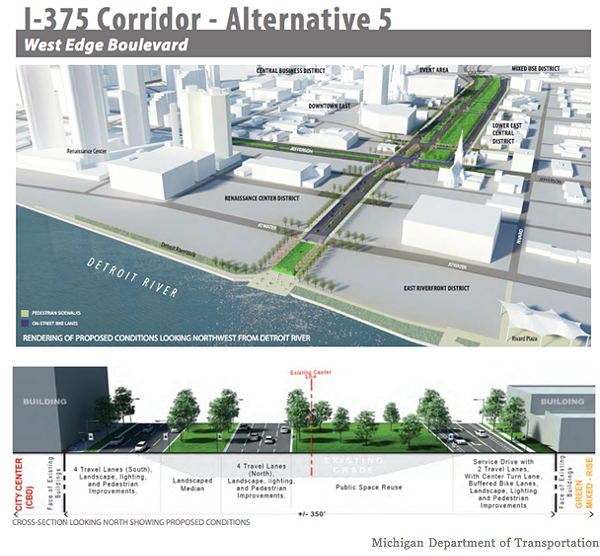

While alternative two was found to be the favorite in the survey that gave immediate neighbors much say, Detroiters citywide most frequently listed proposal five in their top three choices. That option, pictured below, would turn the freeway into a surface-level boulevard at Clinton and convert the northbound service drive into to a two-way local street with bike lanes. It would connect the riverfront connection from East Jefferson to Atwater with bike lanes and free up about 8 acres for possible development.

Of six options, survey respondents most often ranked this alternative in their top three choices (27 percent).

The business publication reports that in 2016, MDOT delayed making a decision on the freeway, saying any future decision on the possibilities for the stretch could be influenced by the East Jefferson/Riverfront study by the Detroit RiverFront Conservancy, Eastern Market's long-range plan, redevelopment of the Brewster Douglass site, and the possibility that Gratiot Avenue will become a bus rapid transit route.

MDOT is currently conducting an environmental study of the various options as part of a five-year plan launched in 2013.