Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

One of the surprising things about Detroit’s diminishing population is how many people claim to know exactly what to blame for the dwindling number of residents. And yet the driving forces are so numerous as to defy definition: high taxes, poor schools, out-of-control crime, unresponsive city government, corruption, pollution, hostility from Lansing, and many more.

Then there are some Detroiters who say the main force driving them away is the city itself. They say that the city sees them as obstacles, not assets. You’ll hear this point of view from residents in the Carbon Works neighborhood, where the expansion of the Marathon Refinery looms large. And you’ll hear it from the people in Delray, all too aware they may be living in ground zero for the anchorage of a new international bridge.

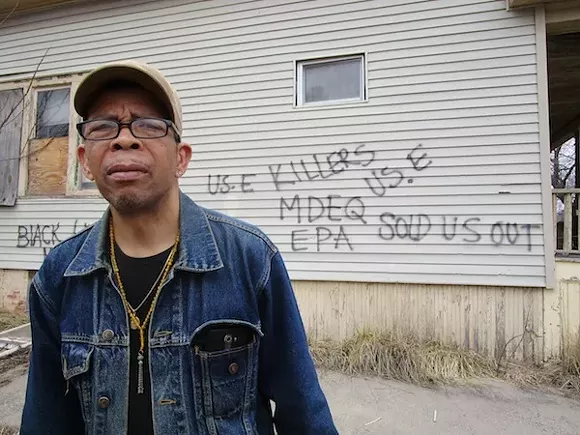

But perhaps nobody defines that struggle between stubborn resident who wants to stay and a city more focused on multimillion-dollar deals than Rufus McWilliams.

McWilliams lives in a modest house on Concord Street between Miller and Strong streets. Originally, the house helped fulfill the promise of a better life that drew his family to Detroit. His father, a Southern-born former sharecropper, bought it in 1955, just seven years after the restrictive covenants that had hemmed in Detroit’s black population were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court. Back then it was a Catholic and Jewish neighborhood slowly turning African-American.

McWilliams was born at the house, and still makes his home there after retiring several years ago from Ford Motor Company’s Rouge complex. He lives there with his wife, a stroke survivor, and he has a sideline in antiques that keeps him busy.

Also keeping him busy is an unexpected sideline in neighborhood activism. You see, these days, McWilliams’ neighborhood is on the decline, and the only entities eager to be McWilliams’ neighbors are large industrial concerns.

That’s not by accident: For almost 20 years, the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation has tried to turn the neighborhood north of his house into a thriving industrial park. McWilliams says that, for a long time, it simply became a “drop zone” that filled up with trash, dead chickens, discarded tires, boats, even dead bodies. The DEGC spent $48,000 to clear away much of the debris in 2009. It was one of the few clean-ups the hardscrabble district, which suffers from inferior municipal services, had seen.

“This area, like a city worker told me, is a ‘no-fly zone,’” McWilliams says.

What businesses have located in the area have often made life difficult for McWilliams and his neighbors. Listen to him discuss his problems for a few minutes, and it becomes clear that the problem hinges on an imbalance of power. As he tells it, the politically connected business owners who want to move in seem almost immune to any complaints, and the longtime residents find it almost impossible to be heard.

“I’ve been in this fight for over 16 years,” McWilliams says, looking through records of his struggle at his dining room table. “Our first incident was back during the Archer administration with [hazardous waste handler] Dynecol, when the kids had to be evacuated from Cooper School over to Burroughs. We tried to get answers, what the chemicals were, why were they evacuated. We got no answers. … I talked to one of the representatives for Dynecol about dumping and crime and the neighborhood. Like most companies, they say they want to be good neighbors and they want to get to know the people. Well, we got no answers.”

Toward the end of the Archer administration, homeowners were told that their new neighbor would be a state-of-the-art automotive recycling center.

It’s what McWilliams and neighbors commonly call “the scrap yard.”

They also say it’s the source of earth-shaking explosions that have tormented them for years. They say that when the facility’s car shredder accumulates enough liquid gasoline from ripping automobiles to ribbons, a spark can set off a blast that rocks the neighborhood.

“We start receiving implosions from that scrapyard right after that shredder went up,” McWilliams says. “The first time I heard one it blew me out the bed. We were receiving six a day, six days a week, for over six-and-a-half years. We called news stations, we called the health department. We got nothing.”

McWilliams says the explosions knock things over and damage plaster walls. He and his wife spent money to update their home just to deal with these potent discharges.

But sometimes the blasts are too powerful for precautions to matter. Ask around McWilliams’ neighborhood and you’ll soon hear about “the big one.”

“When ‘the big one’ came, people’s windows were blown out their house,” McWilliams says. “People were complaining about ceilings falling in. It was so loud. … On this particular day, we got the business: People’s windows, walls, pictures, you know, for years we couldn’t hang anything up on our walls. And if you set something up on the dresser upstairs, an hour later you hear stuff falling from the vibrations.”

McWilliams and his neighbors say their houses aren’t the only things taking damage.

“For all them years we took implosions from that scrapyard, it didn’t only mess up our homes, it messed up the infrastructure,” McWilliams says. “The water pipes, the gas pipes, that’s why you see all the patches in the street, they’re always digging it up.”

He tells us that the scrap yard is part of the multimillion-dollar scrap metal portfolio of prominent, politically connected businessman Anthony Soave. Westland mayor and auto scrap mogul Bill Wild has been part of his management team. And they aren’t the only rich and powerful people DEDC has laid out the red carpet for: The new truck warehouse nearby is owned by Matty Moroun.

If the explosions weren’t enough to disturb the peace, the railroad traffic and now truck traffic make it even harder.

“Sleeping over here is hard,” McWilliams says. “Sunday nights, when that train comes through, ’til 5 in the morning sometimes. Sometimes Wednesday or Thursday nights, sometimes all day, you know, back and forth. … Matty Moroun owns all of this back over here … They’ve got us in their pocket, and we can’t get out.”

But McWilliams is most concerned of all by a neighbor that’s planning an ambitious expansion. That neighbor is U.S. Ecology, a company based in Boise, Idaho, that bought the old Dynecol facility. The company is now waiting on approval of a permit from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality that will allow it to undergo an almost tenfold expansion in the amount of waste it can store and process. The materials handled at the facility will include radioactive fracking waste. It already has permission from the Great Lakes Water Authority to dump 300,000 gallons a day of treated liquid waste into the sewer.

(MDEQ, of course, is the same group that declared Flint’s water safe to drink. Those close to the matter say it’s only a matter of time before the department approves U.S. Ecology’s permit.)

And those are just the problems related to industry. Crime continues to plague the neighborhood just as badly as in other parts of Detroit. McWilliams describes a recent break-in through the front window of a neighbor’s house, and says, “It’s sad that these seniors are being targeted, their homes are being broken into, and nobody cares.”

The elderly ladies on the street are one of the main reasons McWilliams stays.

“This is real, and there’s nothing else really I can do, but just support them and have their back because they’re dying. They’re actually dying,” McWilliams says. “What I hope to accomplish is to open up some people’s eyes, to let them know that these ladies are down here, that we are down here, that we are the real people of this I-94 expansion.”

“They don’t care about the people in this community,” he says. “They want us gone. The best way to get us out is to choke us out. They took out the traffic lights. They even took out the mailboxes.”

McWilliams says even his wife and kids want him to leave. And even he knows he can’t win in the end.

“I don’t know how much time I got,” he says, “but I got to get out of here too.”