Sick of Democrats vs. Republicans? So are Michigan's Libertarians, a party on the rise

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

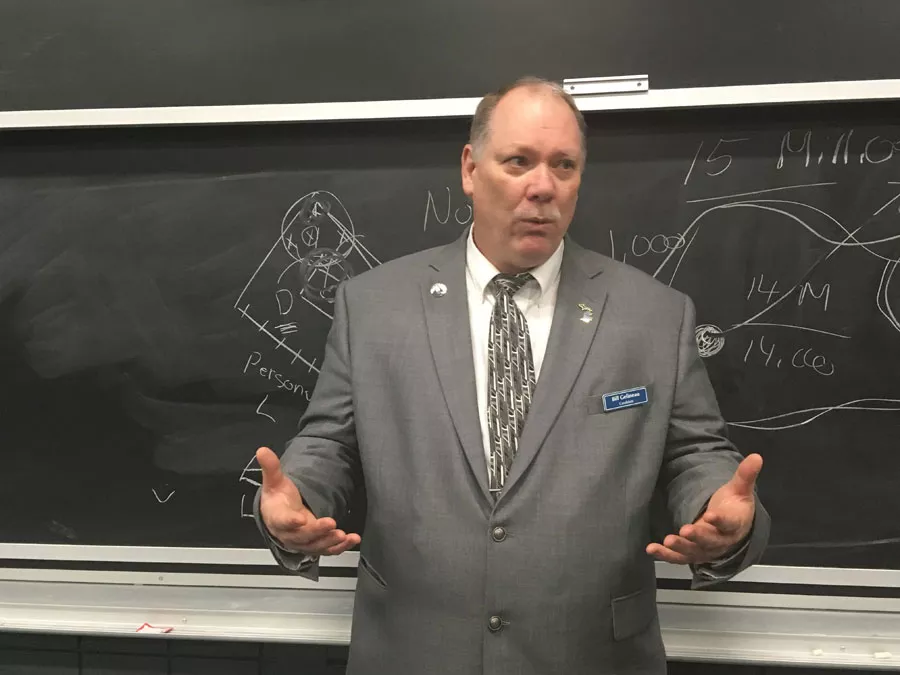

At a campaign stop at Michigan State University last month, Bill Gelineau — the Libertarian Party candidate running to be Michigan's next governor — promises he's about to drop a "bombshell." But right now he's experiencing some technical difficulties.

"I actually brought a visual for this one, but it didn't turn out how like I had hoped, because we didn't get a million dollars to do our stuff," he says while unrolling a map.

Gelineau's referencing the fact that under state law, his major party gubernatorial opponents, Democrat Gretchen Whitmer and Republican Bill Schuette, both qualified for $1,125,000 of public funds to help pay for their campaigns following their primary wins. But even though the Libertarian Party also qualified for a primary election in Michigan this year — its first — Gelineau did not qualify for the funds. The way the law is written, only the top two political parties running are considered "major political parties" and eligible for the money.

Of course, as a Libertarian, the 58-year-old Grand Rapids-area businessman says he would have declined taking taxpayer money on principle, due to his party's core tenet of cutting back government spending.

Gelineau finally manages to balance the map on the ledge of a chalkboard. It shows a the proposed creation of a new county, "Detroit County," made up of Detroit, Hamtramck, Highland Park, Harper Woods, and the Grosse Pointes. Dubbed "Detroit 84," the proposal would also allow for neighborhoods within Detroit to petition for city status as a possible way to create smaller, more manageable municipalities. Gelineau says this could rescue Detroit from what has become an unwieldy bureaucracy, as the massive city has shed population for decades.

"We think it's time to try and bring democracy closer to the people," he says.

The map flops off of the ledge. "We'll just sit this someplace where you guys can take a picture of it later," he says.

In the following days, the "bombshell" proposal makes a relatively tiny splash, getting just brief write-ups in this paper, The Detroit News, MSU's State News, and Grand Rapids' WWTV/WWUP-TV 9 & 10 News. Nevertheless, Gelineau says he is determined to shake up the status quo.

A third way?

Gelineau's bid for governor represents a milestone for the Libertarian Party.

Likely due in large part to the unpopularity of both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election, former New Mexico Governor Gary Johnson earned 172,136 votes as the Libertarian Party candidate in Michigan that year. Under state rules, a party is required to hold a primary election if it earns at least 5 percent of the total number of votes cast in the most recent Secretary of State race, which was 154,040 for the Libertarians in 2014. It was the first time that third-party candidates qualified for a gubernatorial primary in Michigan in almost 50 years; the last time was when James McCormick ran for the American Independent Party in 1970.

Gelineau was serving as the party's Michigan chairman at the time. With less than 10,000 votes separating Trump and Clinton in Michigan, Gelineau says he's drawn plenty of ire from Democrats, who reamed him out for "stealing" the election from Clinton.

"Like they had some right to our votes," Gelineau says. "'You caused Hillary to lose!' What, me, personally?" (It should be noted that Green Party candidate Jill Stein earned 51,463 votes in Michigan in 2016.)

Gelineau believes the Libertarian Party attracts voters from both the right and the left. "We're an equal opportunity offender," he says. "Both political parties were mad at the Libertarians because we messed up democracy, apparently, because we voted for somebody that we believed in."

As Gelineau points out, his platform includes ideas members of both other parties would agree with, with an emphasis on individual liberties. (Individualism is so important to the party that its mascot is sometimes depicted as a porcupine.) Like those on the left, he calls for the decriminalization of marijuana and the expungement of marijuana-related criminal records. He supports same-sex marriage, the separation of church and state, and the right to assisted suicide. He's against corporate welfare and senseless wars. He joins the chorus from the progressive left to abolish U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement — "ICE culture is so poisonous," he says — and calls for replacing it with a new border control agency. Like those on the right, he calls for smaller government, lower taxes, and gun freedoms. He believes partisan district gerrymandering is a problem, and that both Democrats and Republicans are too beholden to special interests.

One of his major campaign points is Michigan's incarceration rate, which he believes is too high, and calls for reducing the number of people in prison by 30 percent by releasing non-violent, low-level offenders. This, he believes, could free up as much as $750 million in funds. "Can you imagine some things that we might be able to do with that money?" he asks the crowd at MSU. "Some educational priorities, perhaps? Maybe we could fix some damn roads?"

It might come as no surprise that a party that places so much emphasis on the individual might contain its share of ideological fissures, and the Libertarian Party has plenty. Gelineau believes Kentucky Republican Senator Rand Paul, a self-described "lowercase L" libertarian, "choked" when he said in 2011 that he would not have voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination by private businesses and organizations. Gelineau says he would have voted for it; he also bucks his party by calling for Michigan's Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act to be expanded to include the rights of transgender people.

"One of the fundamental precepts of our party must be the protection of individual liberties," he says. "And so sometimes the government has to stand in the place of those who cannot protect themselves."

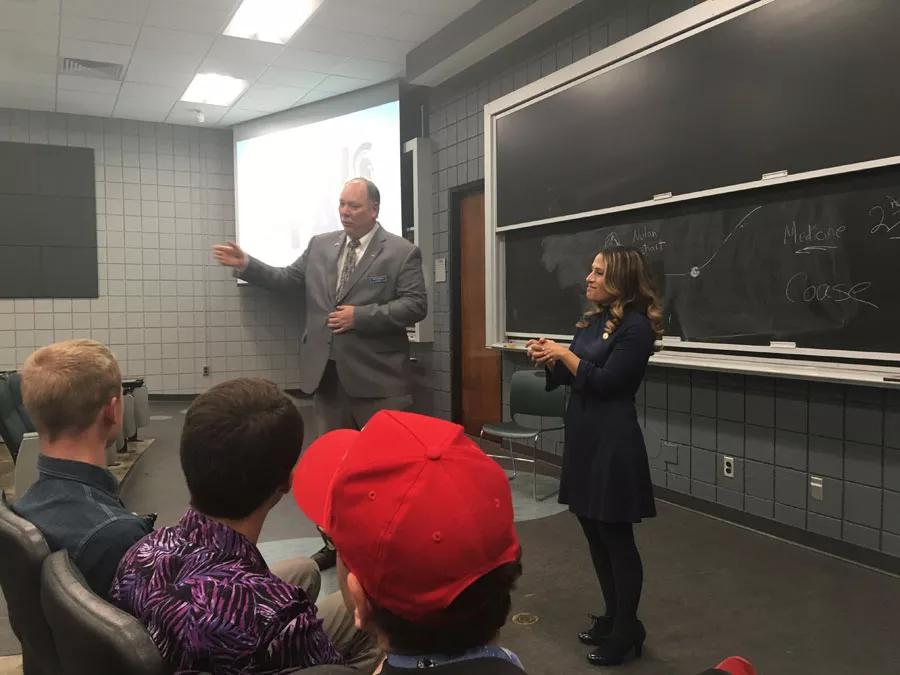

Even Gelineau and his running mate, 41-year-old Auburn Hills businesswoman Angelique Chaiser Thomas, don't see eye-to-eye on everything — both figuratively and literally. Gelineau is tall but soft-spoken, Thomas is diminutive yet fierce. When he calls her to the front of the room to speak at the MSU gathering, he remarks that they are almost certain to be the tallest and shortest pair on any gubernatorial ticket.

A student (wearing both a Trump "Make America Great Again" hat and red Nike sneakers, perhaps consciously flouting the rules of the Colin Kaepernick culture war with a decidedly libertarian fashion statement) raises his hand and asks Gelineau where he stands on the Supreme Court decision regarding the Colorado baker who refused to make a wedding cake for a gay couple on religious grounds. Gelineau agrees that they should be required to bake the cake. He calls it "public square" libertarianism — people should be expected to behave a certain way in public, he says. They can then be free to do whatever they want in their homes, as long as they're not hurting anybody.

The MAGA hat kid is triggered. "That's terrible," he says.

Thomas chimes in, siding with the MAGA kid. "Bill and I don't agree on this, just like many Libertarians," she says. "Our party is rife with dialogue. That's why it's the best party."

Thomas believes that if a business owner wants to discriminate, they should be free to do so. If that means they suffer consequences, so be it. "If you want to be an asshole, be an asshole. You're going to be held accountable," she says. "You don't want to make the cake, don't make the cake. Nobody will patronize you, and you might go out of business."

She turns to Gelineau. "I do think your opinion violates the Libertarian in you," she says. "But I still love you."

Gelineau bucks his party in other ways, too. Another one of Gelineau's campaign "bombshells" is a proposal he calls MI-Way Forward. The idea is to try and curb dependence on Medicaid in Michigan, where some 49,000 births, or 44 percent, were paid for by the program in 2017.

Gelineau proposes the creation of a federal pilot program to ask 5,000 girls from families that receive public assistance to volunteer to delay pregnancy until age 23. Starting from age 17, they would be awarded a cash incentive for each year they avoid pregnancy, with a potential to earn $27,000 by age 23. The result would be less people on government assistance, Gelineau says, citing reports that show women who delay pregnancy tend to be less dependent on Medicaid and other programs.

The MAGA hat kid raises his hand again. Such a plan would require the government to essentially create a database of young women's blood to test for pregnancy hormones— a very anti-libertarian idea that could create a potential "slippery slope," he says.

"I'm sure that Ayn Rand would be rolling in her grave saying, 'This is not a libertarian program.' I'll grant you that," Gelineau says. "But I believe it has libertarian aspects that make it better than what we have."

Gelineau says his goal is not to tear the system down, but rather to "work with the system" to provide alternatives to what's offered by both other major parties. In the case of health care, that would be Medicaid for all from the left, and cruelly cutting many people off "with a meat cleaver" from the right.

Gelineau points to mortgage interest deduction — essentially a subsidy for homeowners who pay interest to banks. "Is that worse than helping some girl that's in abject poverty?" he asks. "I think we have to decide first whether we think it's a problem. If you don't agree with me that girls 15, 16, 17 years old having children is a problem, then we probably don't have anything to talk about. The fact is, I think it is a problem, and I think the majority of people think it's a problem."

Gelineau admits that ideas like Detroit 84 and MI-Way Forward are "edgy." But he maintains he's serious, and not just trying to be funny or draw attention to himself, as he believes Michigan Libertarian Senate candidate Brian Ellison did when he said earlier this year that all homeless people should be armed with shotguns.

"We want to take libertarian ideas to inform what we're doing, but they're not going to chain us," Gelineau says. "I don't envision 'Libertopia.' What I envision is, we have a government as it is, and where do we fit into making that work? For me, it's about how we can move forward, and how we can actually represent our people, but seriously take on the task if given the opportunity."

Thomas says they're trying to come up with ways to curb government spending, to "take away the government's incentive to self-perpetuate and grow, because they tend to do that."

"They pass legislation, and once you spend the money, you're spending the money into eternity," she says. "We're trying to create a conversation. We know a lot of it is unrealistic, but it holds them accountable."

"We're the party that are holding the Democrats responsible for claiming that they are social justice warriors, and we're holding the Republicans accountable for claiming that they're the ones that are for small government," she says.

A Democrat defector

Born and raised in the downriver suburbs outside of Detroit by two Union-supporting Democrats, Gelineau says he grew up sharing his parents' political beliefs. He eventually went to University of Michigan and later, Wayne State University, which is where he says he started to learn about Libertarianism.

"Honestly, in some ways I think the Democratic party left me," he says.

Gelineau says he has long called for ending the war on drugs — something neither other major party embraced until recently, as the public opinion has shifted. "You know, we were for legalized marijuana in 1972. Obama wouldn't even come out for it," he says, licking a finger and sticking it up in the air. "But now that it's become more popular, the Democrats put their finger to the wind and now their value system says, 'Yep, now we're going to let that govern us.'"

Gelineau says further disillusionment with the major parties came after 9/11, as the U.S. entered what would turn out to be seemingly endless wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. He became chairman of Michigan's Libertarian party in 2003, just days after the Patriot Act granted the federal government sweeping powers. "My bona fides in the party come from the fact that I was the first chairman of any political party to come out against the Patriot Act," he says. "You might remember that environment. People were calling up my house. I got death threats. I mean, it was tough."

In 2004, cartoonist Garry Trudeau published more than 700 names of U.S. military personnel killed in Iraq in his comic strip Doonesbury, among the first names released by the government. The final name on the list was Christopher Gelineau. Gelineau did some digging and discovered he was a distant relative who served in the New Hampshire National Guard.

"I thought to myself, what a terrible thing that here my very small family lost someone in this war that I really, really objected to," Gelineau says. He later found out that governors are the commander in chief of their state's National Guard, and could deny a president's request to send troops overseas.

"I said to myself, 'Gosh, if I'm ever in a situation where I could do something about that, I'm going to raise holy hell,'" he says.

Another episode in the Gelineau origin story came in 2012, when Michigan Secretary of State Ruth Johnson blocked Johnson from appearing on the primary presidential ballot. Before running as a Libertarian, Johnson had previously declared his intention to run as a Republican; the party missed the deadline to withdraw Johnson from the Republican race by just four minutes. Since he "lost" as a Republican, the state's "sore loser" law disqualified him from running with a party affiliation in the general election.

Gelineau was heartbroken — Johnson appeared on every other state ballot that year except for Michigan and Oklahoma. "That left a hole in my soul," Gelineau says. "And if you don't think that had something to do with how badly I wanted to get back at them in 2016, you would be mistaken."

When Johnson announced he was running again in 2016, Gelineau dove back in, helping negotiate for the candidate to speak at the Detroit Economic Club and to meet with the editorial staff of The Detroit News, which then officially endorsed Johnson, who then went on to earn those crucial 172,136 votes.

Three's a crowd

Gelineau spent the rest of his term as chairman helping to reform the party's bylaws to conform with state requirements — a "Herculean task," he says — before announcing his intention to run for governor. The first item of business was collecting 15,000 signatures to appear on the ballot.

The party held its primary alongside the Democrat and Republican primaries in August, where Gelineau defeated his only opponent, retired Livonia schoolteacher John Tatar, earning 58 percent, or 3,952 votes. The party held its primary nominating convention in Romulus, where delegates approved Thomas for lieutenant governor. West Bloomfield's Lisa Lane Gioia was selected as the ticket's attorney general candidate, and Gregory Stempfle of Ferndale became the party's secretary of state candidate.

But as Gelineau and other Libertarian Party candidates have found, it can be hard for a third party to even be accepted and accommodated just because of how we are used to thinking about things in terms of being a two-party system.

"The reality of the way the media in our country works is they can't even talk about the fact that we have a multiparty democracy," Gelineau says. "You hear words like 'bipartisan.' Bi means two — Democrats, Republicans."

Republican U.S. Rep. Justin Amash — another self-described "lowercase L" libertarian — tweeted his support of Lt. Gov. Brian Calley for governor in the primary, writing, "There are no libertarians among the Michigan GOP candidates for governor, so I'm voting for the one who earned my respect when we served together in the state House: @briancalley."

When asked about the actual Libertarian Party — the one that qualified for its historic first gubernatorial primary — a campaign spokeswoman later clarified that Amash was voting GOP so he could vote for himself, since you can't split a ticket in a primary election.

‘The reality of the way the media in our country works is they can’t even talk about the fact that we have a multiparty democracy.’

tweet this

Gelineau compares the two parties to gangs — they're the Bloods and the Crips, the reds and the blues. "No offense intended, no community being called out," he tells the crowd of students at MSU of his obviously politically incorrect analogy. "Simply, the point is that our American political parties have become gangs. They protect each other, they cause a lot of chaos, and they don't give a damn what you think. And if you think I'm wrong, ask yourself honestly: When is the last time anybody asked you your opinion?"

He points out the way the system is now, your vote essentially doesn't matter if you're, say, a Republican living in a heavily Democratic area like Detroit. You shouldn't have to relocate to make your vote count, he says.

"Your opinion really doesn't count, because they've made the system where it doesn't work," he says. "All it does is ensure their continued existence and let's be honest, the two parties are pretty similar, as much as we want to say they're different."

A long shot

Gelineau knows the odds of actually being elected governor are insurmountable. His campaign budget is dwarfed by his major party rivals; he has just $70,000 in his coffer, with more than half put in by Gelineau himself. You can't buy TV ads with that kind of money, though Gelineau says he has bought radio and billboard ads in the weeks leading up to the November election.

Gelineau also says he was not invited to join Whitmer and Schuette in the two upcoming televised debates on WOOD on Oct. 12 and WDIV on Oct. 24. Oftentimes, TV stations use 10 percent polling as a threshold to invite candidates to appear. A recent Free Press poll found Whitmer with 45 percent support, Schuette at 37 percent, and Gelineau at 2 percent, with 5 percent undecided. ("That's another thing they've gerrymandered," Gelineau says of the debates. He plans on taping the debates and splicing himself in and releasing it on the internet.)

That said, Gelineau has lowered his expectations — short of winning the governorship, if he wins 5 percent of the vote, the Michigan Libertarian Party can maintain its primary-qualifying status in 2020. That could lead to other contested races, which would cause candidates to work harder and get a lot more attention than they would otherwise. But even scraping together that 5 percent would be a surprising feat.

Our interview with Gelineau comes against the backdrop of Trump's nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, which quickly devolved into an ugly, all-consuming culture war with scandalous confirmation hearings, street protests, and both sides falling largely along partisan lines. At times like this, it can feel like both parties are engaged in a zero-sum, scorched-earth war for domination of each other. Gelineau believes a robust multiparty system could help ease those tensions, and lead to a better public discourse.

Gelineau says he could imagine a world where Libertarians have a few seats in the legislature — along with other parties, like the Green Party.

"Imagine how different the negotiating process would be," he says. "We'd have different coalitions that would come together on various things. You know, we'd sometimes work with the red team, and we'd sometimes work with the blue team, and we'd sometimes work with the green team. Wouldn't that just be better? I just think it'd be wonderful." It's not impossible, or far-fetched — Gelineau points out that democracies in countries like Austria, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, India, Mexico, and New Zealand, among others, all have multiparty systems.

Until then, Gelineau says he hopes his run can at least help keep the momentum going. "I'm hopefully leaving a track that allows the Libertarian Party to move forward," he says. "I may not get over the hill this time, but we will the next time."

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.