Red Wings owner estimates new arena lifespan to be 48 years

Bold vision for new Detroit arena district, but how long will it be around?

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

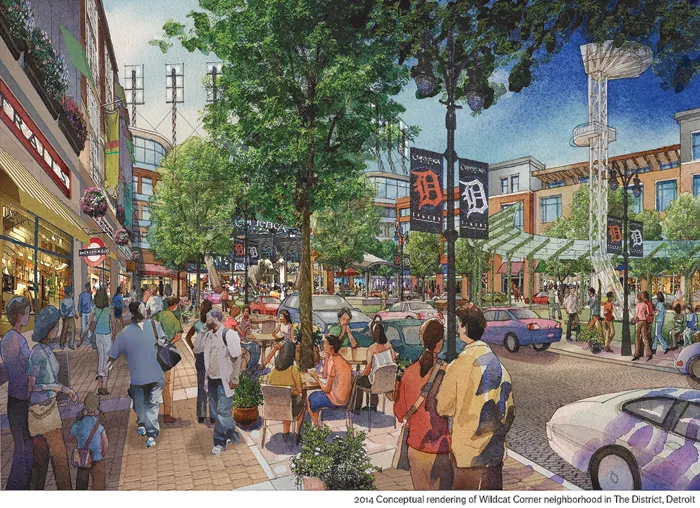

On Sunday, the front-page, above-the-fold headline of the Detroit Free Press must’ve jumped out at readers: “Hockey, Housing and a Whole Lot More.” Olympia Entertainment of Michigan, an arm of Detroit Red Wings owner Ilitch Holdings Inc., had made a grand announcement: It had a vision for the city’s downtown entertainment district. There were renderings to prove it.

That’s not to say what the Ilitch organization conceptualized for the massive 45-block entertainment district wasn’t impressive. It was. Besides the $450 million arena, equipped with 20,000 seats for hockey fans, Olympia said it would invest “tens of millions of dollars” in public infrastructure improvements, including lighting, sidewalks, green spaces, and streets. It planned to invest $200 million in new, mixed-use development to occur concurrently with the construction of the arena. The company planned to construct residential units, which would help fulfill the growing demand for housing downtown. If Olympia follows through on the investment, it would net them a $62 million tax credit from the Detroit Downtown Development Authority (DDA), the entity that will own the arena and lease it to the Red Wings’ owner for as long as 95 years, according to city records.

Besides the Freep’s coverage on the plan, Crain’s Detroit Business followed with an equally impressive spead. The reports on the arena district concept were, more or less, eagerly optimistic — and rightfully so: For years, Detroiters sat on the sidelines awaiting the Ilitches’ move to develop a vast amount of property surrounding their Fox Theatre. This was the payoff: If implemented, the Ilitches’ plan would bring new shops, restaurants, bars, stores. (Without divulging further into specifics, a website launched Sunday, DistrictDetroit.com, offers an outline of what to expect if everything falls into place.)

By evening, the local TV news stations injected their palpable sense of optimism about what was entirely a concept into the air. One reporter asked viewers to “imagine” the blighted, empty space of the Cass Corridor behind her being transformed into a vibrant entertainment district.

What was missing, it seemed, was a larger dose of realism. That is, unless you read Stephen Henderson, editorial page editor of the Freep, and his Sunday column.

“In addition, there is some reckoning that needs to be done of the family’s long-tenured ownership of many properties in this area,” Henderson wrote. “They held on to property while the neighborhood deteriorated — arguing, convincingly, that the time and economic conditions weren’t right for development — but now promise to move forward with what they own. Promises have been made before, some kept (think Fox Theatre) and some not realized (think Detroit’s Wrigleyville).”

What Henderson seemed to be saying was this: Yeah, this is outstanding, but let’s pull back on the reins a bit and figure out what needs to be done to make it a reality. Because, haven’t we been here before? The Ilitches themselves have proposed a number of such visions that went nowhere, as Metro Times previously reported.

Spread the love

It wasn’t all pleasantries in the world of Hockeytown this weekend: Deadspin, the sports vertical of Gawker Media, posted a link on Twitter to a piece written earlier this year by Bill Bradley, a writer based in Brooklyn, N.Y. The tweet said this: “As pretty as the Red Wings’ arena district may look, it’s still a massive scam, and Detroit’s the victim.”

The message wasn’t well received by some.

“Oh yeah, @Deadspin, bc the city of Detroit hasn’t made a nickel off the Red Wings,” wrote one user. “You guys are a bunch of ass holes, just shut up.” Said another user: “@Deadspin, it’s funny how I’ve loved reading deadspin’s spins on things. Not this time. Any educated metro-Detroiter is very excited.”

The piece in question by Bradley — titled, “Detroit Scam City: How the Red Wings Took Hockeytown for All It Had” — centered on the splendidly complex methods sports team owners use to finance new homes for their franchises — typically using public tax dollars to accomplish the task.

Bradley cites a report from Andrew Zimbalist, a prominent sports economist who reviewed stadium welfare’s impact on a major metropolitan area. Zimbalist found “no significant difference in personal income growth from 1958 to 1987 between 36 metropolitan areas that hosted a team in one of the four professional premier sports leagues, and 12 otherwise comparable areas that did not.”

As Bradley wrote, that’s “a long way of saying: The franchise owner gets richer, but the city’s residents don’t.”

Here’s a question to consider: What happens when this new arena is determined to be inadequate? According to city records, Olympia has said it estimates the lifespan of the new arena to be 48.5 years. What will come of the facility when that time comes? Will Olympia renovate it, or seek to demolish it? That’s unclear. And yet that’s what the new arena plan appears to offer: If implemented, Detroit will enjoy a beautiful new arena, with hopefully, some new housing and stores — for, maybe, a half-century.

And what if Detroit hasn’t paid down the state’s $450 million in bonds before that moment? The Joe Louis Arena is one of the oldest facilities in the National Hockey League, at roughly 35 years. If the new arena lasts that long, downtown Detroit tax dollars will be spent about as long as the venue operates. In Florida, officials in Miami-Dade County issued $500 million in bonds to finance the construction of Marlins Stadium. By the time those bonds mature, in 2048, it will cost taxpayers $1.2 billion, according to the Miami Herald.

As local writer Jeff Wattrick, now managing editor of WDIV Channel 4’s website, put it at Deadline Detroit, “Granted, that number is smaller in real dollars when you adjust for inflation. However, that’s cold comfort if the Marlins decide they need a new park prior to 2048.”

And then there’s the arena’s financing itself, a particularly interesting facet that was mostly left out of last weekend’s coverage, likely because it’s been extensively reported on. It bears repeating, though: As Metro Times reported in an exhaustive cover story earlier this year, no money for the project comes from Detroit’s general fund. The state of Michigan will issue 30-year, tax-exempt bonds to finance construction, which would be secured by three revenue streams:

• ● The DDA would capture roughly $13 million to $15 million in state school taxes the state Legislature authorized the authority to utilize specifically for the new arena district; the state has said it replenishes the lost school taxes;

• ● Another $2.15 million would be captured by the DDA for the project;

• ● Olympia would contribute $11.5 million to the pot, and would cover any cost overruns in the construction of the arena.

Again, that’s no general fund dollars. The increased property taxes generated by the project would be captured by the DDA for future development, a mind-numbing financial tool called tax-increment financing (TIF). The idea, supporters explain, is that a city can essentially create new tax revenue for redevelopment through TIF, that otherwise would’ve never existed. Detroit officials have estimated it would generate $15.8 million in new income tax revenue for the city over 30 years, according to city records. That’s based on Olympia’s projections of 8,300 construction jobs needed for the rink, as well as 400 new hires to operate the facility.

Another point that’s been missing from the dialogue about the arena (perhaps because it’s a horrendously dense topic to write about): To facilitate the repayment of the bonds, the DDA had to extend the life of its TIF plan, a guiding document that dictates how long it can continue capturing property taxes that otherwise would flow to the city’s general fund, libraries, Wayne County and more.

The way a study from the U.S. PIRG Education Fund described it: “The ideal outcome of a TIF district is that a jolt of investment sparks new economic activity in a stagnant area, creating economic activity benefits the broader community and increases the value of land within the district when it returns to tax rolls.”

The PIRG report continued: “Poorly targeted use of TIF, however, can actually produce the opposite effect — sucking further investment out of economically challenged areas to facilitate new ‘greenfield’ development.” The report suggested state governments, which authorize the use of TIF, should adopt a requirement to limit the use of the financial tool, one of which was the “maximum duration over which a TIF district can remain in place should be firmly fixed.”

“Even before the maximum duration expires, tax revenue from TIF districts should return to the tax districts that normally claim it as soon as the investments envisioned in the initial development have been paid for, rather than being reserved for additional discretionary spending within the TIF district.”

According to DDA documents, later approved by the city, the authority’s TIF plan was extended for 20 years, to fiscal year 2044-45. That means the DDA TIF plan — first enacted in or around 1978 — will have existed for 65 years in order to secure bond payments for redevelopment projects, such as the new Red Wings arena.

That’s nearly three generations of Detroiters who wouldn’t enjoy the added boost of revenue to their general fund, which supports basic city services like police and fire protection.

The arena will be situated as a bridge between the up-and-coming Midtown district and downtown. Supporters have said the use of tax-increment financing was a necessary decision in order to ensure Detroit, which is bankrupt, could finance such a massive undertaking. But, with a flurry of investment and development happening in Midtown and downtown, one could assume it would eventually spill over into the new arena district — with or without the use of a TIF deal. The only certainty is that any new development in a TIF district leaves the city deprived of vital property tax revenue at a time the city could use it the most — and for who knows how long.

That’s the juggling act, though, with tax-increment financing: By facilitating the development, supporters have said, it will bring jobs, boost income tax revenue for a city, somewhat, and, hopefully, increase property values, and property tax revenue, of the area surrounding the DDA's TIF district. If that’s a guarantee, though, is unknown.

The DDA receives anywhere between $12 million and $17 million annually in revenue generated by its TIF, according to authority documents. Once the new arena is constructed, that figure will likely continue to grow over the next 30 years, and that increase in property tax revenue will continue to be captured by the DDA.

That’s what Detroit has forgone. For a vision.