The QLine has begun cracking down on people who hop on the streetcar without purchasing a ticket by issuing misdemeanor citations that carry penalties of up to 90 days in jail or up to a $500 fine.

At least 17 citations were issued last week alone, according to a spokesman for the QLine. The fare-evasion enforcement effort began about three weeks ago, following a one-month period in which streetcar ambassadors issued “last warnings” to riders caught without a ticket.

“We wanted to allow people to get familiar with the streetcar and essentially exhaust every means of allowing people to do the right thing before we started fining people,” QLine spokesman Dan Lijana says.

The QLine operates on a “trust but verify” system, meaning you can get on board without showing a ticket, but transit police or streetcar “ambassadors” can ask for proof you paid. The 3.3-mile rail line was free to ride from its May 12 opening through Labor Day. Since then, ambassadors have been dispatched along the route to help riders purchase tickets and get acquainted with the streetcar.

Now, five months into standard operations, people caught on the QLine without a ticket can be issued a misdemeanor citation that requires a court appearance, where a judge decides how stringent a penalty to impose.

The maximum $500 fine is five times higher than the maximum penalty for fare evasion on the People Mover or a DDOT bus, according to a DDOT spokeswoman.

“We have an interest in people paying, we don’t have an interest in penalizing people,” Lijana says, pointing out that fines for fare evasion go to the city, not the streetcar. “There’s many instances where a transportation line increases their enforcement and that word of mouth, that example, and the specter of getting a citation that is many more times expensive than that ticket is a real deterrent for people to avoid paying the fare.”

But Detroit’s penalties appear to be more severe than those of other cities. In Portland — one of the places M-1 Rail looked to when crafting its policy — people caught fare-dodging on the streetcar are required to pay a $175 ticket. In Washington, D.C., another system Lijana says M-1 Rail used as an example, fare evasion can mean up to a $300 fine or up to 10 days in jail, but those penalties apply only to the Metro system. The city’s independently operated street car is still free and its director says a fare-evasion policy has not yet been developed.

Portland, Washington, and many other cities with public transit systems like Detroit treat fare evasion as a misdemeanor. But some transit agencies and local officials have been re-evaluating that approach as they respond to criticism that the practice criminalizes the poor.

The Portland area’s regional rail system last year began resolving citations without sending them to court, calling the new protocol a “much fairer deal — especially considering a court record can affect [people's] ability to get a job, rent a house, or serve in the military.” The shift in approach came after a Portland State University researcher found that black riders caught riding without having paid were banned from the TriMet transit system more often than white riders who failed to pay. TriMet also recently proposed reducing the fine for first-time fare evaders from $175 to $75. In a phone call last week, the director of Portland’s city-specific streetcar said his system would soon follow suit in loosening penalties for fare evasion. In Washington D.C., a bill recently introduced to decriminalize the offense has support from the majority of the district’s councilmembers. In Manhattan, District Attorney Cy Vance recently announced he would no longer prosecute turnstile jumpers on the subway. Shortly after, two New York state lawmakers announced plans to introduce a bill to decriminalize the offense.

In New York City, arrests for turnstile jumping have been known to clog courts and disproportionately target low-income and minority residents. Last year, a nonpartisan, independent committee for criminal justice and incarceration reform in the city recommended that, for those reasons, such low-level offenses should be treated as civil infractions.

“It has consequences when you put people in the criminal system,” says Jonathan Lippman, the former chief judge of the New York Court of Appeals and chairman of the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform. “Even very minor offenses can have consequences for employment, housing, and immigration — and these kinds of offenses are usually caused by deeper issues that may be homelessness or mental illness."

“Bringing criminal charges against these kinds of persons doesn't help, it only exacerbates the situation.”

Detroit’s policy for QLine fare evaders was adopted by city council unanimously last May, after M-1 Rail operators worked with Mayor Mike Duggan's administration to draft the ordinance.

The city says it had no choice but to criminalize fare evasion on the QLine because Michigan law states that civil infractions can only be written for independently operated motor vehicles — or vehicles where a driver can move around at their will.

“The city's authority for creating prohibitions against particular activity comes from the Home Rule City Act,” Detroit Corporation Counsel Lawrence García said in an email. “That statute does allow for civil infraction, but only as to motor vehicle-related violations. By contrast, under the same statute, the city may invoke its police powers to prohibit any activity against public safety and welfare, but the only sanction available for such prohibition(s) is a misdemeanor.”

The citations for failing to pay to get on Detroit’s two other public transit systems reflect that statement. Skipping the bill to get on a DDOT bus is treated as a civil infraction, with a $100 ticket; dodging the fare on the People Mover is a misdemeanor offense.

A spokeswoman for the People Mover says the monorail did not issue any fare-evasion citations last year. DDOT spokeswoman Nicole Simmons did not say whether any were issued on the DDOT bus.

It’s unclear what penalties have been imposed on QLine fare-dodgers so far. DDOT also did not respond to an inquiry on whether two riders cited had yet appeared in court and, if so, what penalties they’d incurred.

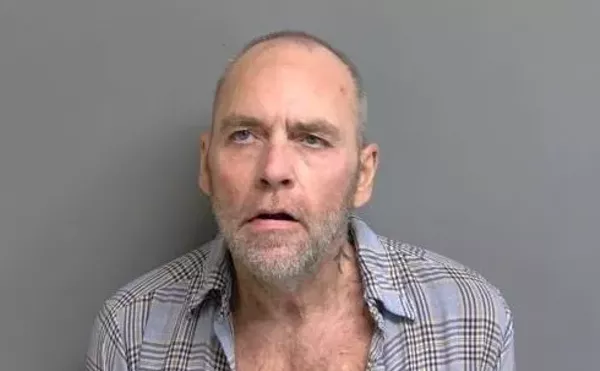

However, we may be able to extrapolate how much first-time offenders will get fined based on one rider’s experience. QLine rider Matt Terrian tells Metro Times that a transit officer told him early this month that he could expect a fine of $150 for not paying his fare. Terrian had been without a ticket because he says the kiosk at the station where he boarded the streetcar wasn’t working.

“It's absurd that they would enforce a penalty for not having a ticket when you cannot even reliably purchase a ticket at certain stops,” Terrian says.

The QLine has contracted with DDOT for nine transit officers and there are at least two on or around the rail line at any given time, according to Lijana. Transit officers can also issue citations for things like eating or drinking on the streetcar, and listening to music without headphones in. Most commonly, the transit police issue tickets for cars parked along the QLine tracks, Lijana says. Those tickets are $650 a pop, plus a car tow.

Lijana indicated the fare enforcement effort was always in the cards and that it wasn’t prompted by any specific incident. He did acknowledge that there are people skipping the bill before boarding, but he said those people, for the most part, “are not regular public transit riders.”

When asked how the QLine’s finances are doing, Lijana says it’s too soon to tell with the streetcar having been in standard operation for only five months. Lijana did say cash payments have exceeded expectations and the QLine’s farebox recovery rate is thus far above the national average of about 20 percent. Fare recovery, he says, refers to what percentage of a dollar is returned from fare collection relative to a transit system’s operational cost.

This story was updated at 10:01 a.m. on Feb. 27 with the latest number of citations issued for fare evaders on the QLine.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.