THE FOOTPRINT OF the proposed $650-million Detroit Red Wings arena and entertainment district near downtown has been widely described as an economic dead zone in need of rejuvenation.

And, most have argued, Olympia Development of Michigan’s full proposal — a $450 million new arena for the Red Wings and $200 million of additional spinoff development — could be the anchor project needed to breathe life into the south end of the Cass Corridor. If it comes to fruition, it would “fill what’s largely a dead zone between thriving areas in downtown and Midtown and create something Detroit can trumpet,” the Detroit Free Press editorial board wrote last month.

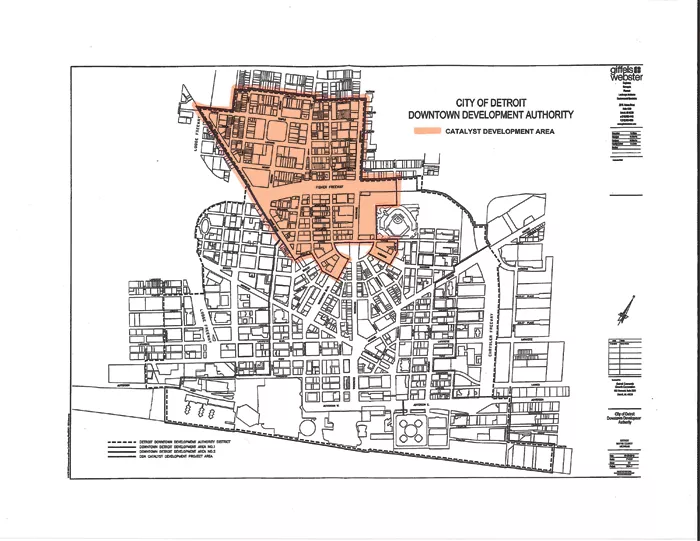

At this point, it’s virtually guaranteed the roughly 45-block area will gain the new arena, bounded by Woodward, Cass and Temple avenues and I-75.

But it’s the second half to the puzzle, the $200 million in spinoff development, that has received little attention since the deal first surfaced in late 2012.

Under the deal, the Downtown Development Authority, a city entity staffed by the quasi-public Detroit Economic Growth Corporation, would own the arena and lease it to Olympia. DDA spokesman Bob Rossbach tells Metro Times that, in its agreement with the authority, Olympia would either invest or “cause to invest” at least $200 million in the area around the arena.

Rossbach says the spinoff development could include housing, office, retail, restaurants and entertainment — anything, really — and would be fully constructed by five years after the date of the arena’s first event. He says Olympia’s the logical party to ask what’s planned since it’s the company’s responsibility to “create those developments,” but the company is still planning.

“It is still too early in the process and the information you are requesting is not finalized,” Olympia said in response to questions about tenants, specific projects or designs, parking, and whether private investors will be sought for the development area.

Though the company did add this: “In addition to the events center, there will be a mixed-use district of office, retail, entertainment and residential space and we have researched and continue to research virtually every mixed-use district developed over the past decade in North America.”

As noted researchers and academics have pointed out, those mixed-use districts tied to arenas don’t have the best track record. And should Olympia balk at the bill, there’s little punishment on the other end.

If $200 million of investment lands in the arena district within the five-year window, the DDA would credit Olympia with $62 million for the ancillary development. If Olympia defaults on that five-year commitment, the new Red Wings arena would still move forward, but Olympia would lose that $62 million credit, city records show.

David Whitaker, of the city’s Legislative Policy Division, wrote in an Aug. 29 memo to City Council: “There appears to be no other specific consequences associated with [Olympia’s] default on this commitment. The current framework for this deal entails little to no risk to [Olympia] with the potential for significant revenue profit.”

It’s likely that the success of the proposed district will hinge on that additional ancillary development that Olympia, the real estate arm of billionaire Red Wings owner Mike Ilitch, intends to attract. Gov. Rick Snyder, a proponent of the deal, said as much last year. The incentive for Ilitch is the possible link-up between his wife Marian Ilitch’s Motor City Casino, as well as the couple’s Fox Theatre and Comerica Park.

“It’s something that hopefully will be a tax-base generator,” Michigan’s Republican governor told reporters last September. “Not the arena as much per se, but all the surrounding development.”

But what will $200 million actually look like, considering Olympia embarks on it at all? Would it be enough to fill the gaps in the proposed 45-block district that includes the Ilitch-owned Fox Theatre and Comerica Park?

Andrew Zimbalist, a sports economist at Smith College in Massachusetts, says these deals typically require the sports team owner to take charge in attracting private investors for spinoff development.

“Unless [Ilitch] is going to do it, it’s quite unlikely that something’s going to happen,” he says.

The planned arena would host a multitude of events, possibly as many as 250 a year, according to Olympia. But, Zimbalist adds, “There’s not going to be enough consistency in the kind of events … that would make it easy for a department store to say, ‘I want to be next to this arena.’”

It is possible the level of investment could exceed $200 million if Olympia makes a full-throttled effort to attract private developers. With a proposed stop along the incoming Woodward Streetcar Line near the arena district, transit advocates say that alone could spur investment.

But, Zimbalist says, Olympia has to “have a critical mass of investments that are committed” in order for the ancillary development to take off.

Neil deMause, a New York-based journalist who has written extensively on sports stadium financing, says Olympia’s vast proposal is likely unprecedented.

A vocal critic of public funding for sports stadiums, deMause says if Olympia’s commitment to the ancillary development is capped at $200 million, that should raise concerns.

“$200 million’s not going to build you an entirely new swath of downtown; I think that’s pretty clear,” he says. “If it’s at least $200 million, then sure, this really could take off, but I can’t think of an arena anywhere that has” filled 45 blocks with development.

The deal would have a greater chance of success if there were a stipulation in the agreement that says a certain amount of construction has to be completed by a set date, deMause says.

He echoes other experts who say the success of sports facilities with proposed spinoff development varies from city to city. But, he says, “Whatever impact you get from a sports facility disappears as soon as you get a block or two away from it. It’s not like there’s no benefit, but it seems like it’s an awfully big public cost just to incentivize a project that may or may not happen.”

Tim Chapin, chair of Florida State University’s Department of Urban and Regional Planning, has studied the impact of so-called catalyst developments across the country.

“Some projects do a better job of spinning off development than others,” he says, but it depends on having a “good plan for the area around the facility, and not just a plan for the facility.”

How Olympia chooses to handle crowds, in particular with parking, will dictate the new arena district’s success, Chapin says.

Several new parking structures surrounding the arena were spelled out in the memorandum of understanding signed between Olympia and the DDA last summer as possible projects that could be constructed.

Chapin says spinoff development is less likely to take place with “facilities that surround themselves with … big parking structures [so] people can walk across the skywalk into the facility, without ever having to step [out of] the arena.”

Momentum plays an integral role, says Chapin, who hasn’t followed the development of Olympia’s deal. Deals like Ilitch’s catalyst development that have been successful have “other projects that are linked to, or otherwise sort-of planned concurrently with the investment,” he says.

“The arena doesn’t change real estate markets," Chapin says, “but the arena can be synergistic with nearby projects.”

Nearby momentum isn’t a guaranteed slam-dunk, though, Chapin says. A developer can’t “just plop an arena down in a really beat area and assume good things [will] happen,” he says. “These projects tend to not be good lead projects. They tend to be good next-wave projects.”

Detroit Emergency Manager Kevyn Orr acknowledged to Bloomberg last summer that questions surrounding large-scale arena deals — including “Does this really pan out? — are common, but Detroit needs all the help it can get, despite the concerns.

“The reality is we are so needy of some economic development, I can’t see how we don’t pursue it because, if we don’t, what’s left?” he said.

As DDA spokesman Rossbach put it to Metro Times, it’s Olympia’s prerogative to follow through with the spinoff development. And under the agreement, Olympia is obligated to secure or fund $200 million of additional development — if the company wants to receive additional funds from the DDA for spinoff projects. As city documents have shown and project backers have reiterated, that could mean anything: parking structures, retail, offices, housing, restaurants. Anything, really.