For half her young life, Laken Dreilich, a pretty high school senior with a passion for cheerleading, has been living with the turmoil spawned by a dispute over something as mundane as bricks.

At first she was too young to comprehend much of what was going on. But as she entered her teens, Laken became more and more aware of the situation confronting her family. The weight of financial problems caused by seemingly endless legal battles, the stress of years-long efforts to fend off eviction from their Shelby Township home, and the fights all this ignited between parents Marie and Roland took a terrible toll.

"It was all so upsetting," says Laken, sitting at the kitchen table with her mother in a home they now rent. "I couldn't handle it anymore, because it ruined our lives. We never used to fight."

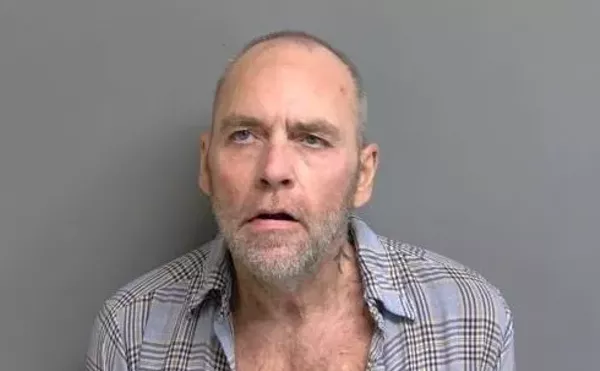

She just wanted it to go away. But it wouldn't. So she left, spending every hour possible at her boyfriend's home in an attempt to escape the atmosphere that was poisoned after contractor Salvatore Viviano — a man with a history of violent crime, drug use and mental problems — filed a lawsuit accusing the Dreilichs of cheating him out of nearly $50,000 for brickwork on the home they built in 1999. The Dreilichs lost that lawsuit in a Macomb County court action that can best be described as drawn-out and convoluted.

The second time the Dreilichs and Viviano clashed in court was in November 2006, as the family made a final attempt to keep their home.

Viviano didn't respond to requests to comment for this story, but his business partner and lifelong friend Dominic Matina did.

The Dreilichs, who attempted to show that fraud was a key element in the loss of their property, and that at least $200,000 in equity at Highbury Court was the motivation, named Matina along with Viviano and several others in a suit filed in 2005.

The judge hearing that case didn't buy the claim, and the Dreilichs were forced out.

It was only justice, says Matina.

In court documents the Dreilichs contend Dominic Matina and Sal Viviano are cousins; Matina told us that's just how the two men, friends since they were kids, refer to each other.

Relations between the two have not always been smooth. In a 2005 lawsuit that was dropped before going to court, they accused each other of misappropriating funds from PIO Construction, a company they jointly own, and of physically attacking each other.

But that bad blood paled in comparison to Matina's opinion of Marie Dreilich.

Rather than being a victim, says Matina, Dreilich is a canny operator who connived for years to continue living in a 5,000-square-foot home without paying the mortgage or rent. Dreilich acknowledges that she constantly maneuvered to stave off foreclosure and then eviction.

"I was doing everything I could to keep our house," she says. "And I kept hoping someone would see what was really going on."

As far as the allegations of wrongdoing leveled against Viviano, Matina and the brothers of both men, Dominic Matina says that's all they ever were — allegations.

"Every time she has to prove what she's claiming, she can't," he says.

Her record in court is proof of that, he observes.

The two Viviano brothers and three Matina brothers who went to court to defend themselves against the Dreilichs are the real victims in this story, says Dominic Matina.

His view is that the Dreilichs got in over their heads when building the home on Highbury Court, and that Salvatore Viviano served as a convenient scapegoat for their problems.

But that's a radically different perspective than the one at the Dreilich's current home, a spacious Shelby Township rental instead of the showplace they once owned.

While mother and daughter talk, Roland is at work, putting up drywall as he has for most of his life. In a separate interview, he too talks about the strain all this has put on his family, and the difficulty of dealing with the loss of the home he worked so hard to obtain.

"When I think of all those hours I worked, all the weekends and holidays spent on the job, to end up with nothing …" he says, his voice trailing off.

And how does he feel toward Viviano?

"I wanted to kill him," says Roland. "But me going to prison wouldn't have done anyone any good. I still had a family to support."

Marie, on the other hand, did go to jail: twice for issues surrounding a personal protective order one of her former attorneys had issued against her, and once for filing fraudulent liens on property owned by Viviano and his associates.

It was an ill-conceived tactic she thought would save their house. Even now, she considers the crime a principled act.

"I wanted Laken to be proud of me for standing up for our rights," explains Marie when asked how she thought her daughter viewed her refusal to give up. It is a plea for understanding as much as a statement.

"I am proud of her," responds Laken. "But I think she took things too far."

She also went over the edge.

"The hardest part of the whole thing," says Laken, "was seeing my mom go crazy."

But Marie Dreilich's mental state isn't the only thing that's bizarre about her family's story over these past eight years.

We pick up that story at the end of 2001, as the initial lawsuit brought by Viviano over the brickwork neared its conclusion.

WHEN KAREN MET MARIE

It was chance that brought Marie Dreilich and Karen Stephens into contact. A shared belief that the same lawyer had wronged them both pulled the two close, and facing adversity together cemented their bond.

That's one way of looking at it.

Another is through the eyes of the man who brought both into the same orbit, Bloomfield Hills lawyer Paul Nicoletti. In a court filing he said the strong bond between the two women was based on shared "delusional behavior."

In regards to Dreilich, a psychiatrist who examined her doesn't share that armchair analysis. Evaluated as part of an agreement between the Macomb Prosecutor's Office and one of Dreilich's attorneys, the exam's purpose was to ensure she was capable of participating in her own defense against the fraudulent liens charges.

The psychiatrist did describe Dreilich as histrionic, and noted that she appeared to be "highly preoccupied with her longstanding legal entanglements" with Viviano. She also had difficulty accepting responsibility for her role in the legal mess she was embroiled in.

But her "thought processes appeared to be well organized," wrote the shrink, and Dreilich demonstrated no signs of "delusional paranoia."

There is no such report in the public record describing Karen Stephens' mental state. By their own admission, though, she and Dreilich do make an odd pair.

Stephens has a master's degree in library science from Wayne State University and spent time as a corporate researcher before going to work as a middle school teacher and librarian. Dreilich attended community college and worked as a secretary before legal battles consumed her life.

"She's always positive and bubbly," says Dreilich about her friend. "I'm the negative one."

Stephens is organized and meticulous; Dreilich pushes things to the last minute, her records often in disarray.

For the past four years, Stephens has been someone who Dreilich could lean on for support. "If I didn't know Karen, I don't know where I would be," says Dreilich.

This is how they became a pair of thorns in Nicoletti's side:

The Dreilichs had been through three lawyers in less than two years, and were looking for attorney No. 4 at the end of 2001, as Salvatore Viviano's initial lawsuit against them neared its conclusion.

The central issue was bricks: How many had actually been used in constructing the Dreilichs' home in Macomb County? An expert was brought in by the Dreilichs to render an opinion, and the conversation turned to lawyers. The expert recommended Nicoletti.

Dreilich, after three bad experiences, was wary when she contacted him. To help put her mind at ease, Nicoletti suggested she talk with Stephens, whom he'd represented in several cases.

Stephens spoke highly of the attorney, and the Dreilichs hired him. But the relationship lasted only about a month before they had a contentious falling out over tactics and an order allowing Nicoletti to withdraw from the case was issued. The judge also allowed Nicoletti to place a lien on any settlement. (Dreilich would later file a lawsuit against Nicoletti alleging malpractice, fraud and perjury. She also filed a complaint with the Attorney Grievance Commission. Neither the court nor commission found any wrongdoing on Nicoletti's part.)

Immediately after the acrimonious split, Dreilich expressed her concerns about Nicoletti to Stephens, but she "did not want to believe" them, Dreilich noted in a court filing. About a year later, in October 2003, Stephens called Dreilich to say the "allegations against Nicoletti appeared to be true," according to a court filing.

Nicoletti, in an interview with Metro Times and in court filings has denied any improper actions on his part in regard to his dealings with the two women.

The dispute between Stephens and Nicoletti involves his handling of a lawsuit brought against Stephens by a company named Canyon Construction. In that case, Stephens was sued after refusing to finalize purchase of a custom-built home because of numerous construction problems. (Although not a litigant in that case, Salvatore Viviano was a factor. His company's brickwork was allegedly flawed because the mortar had been improperly mixed, causing the bond to be dangerously weak.)

In 2003, according to court filings, Stephens agreed to settle for slightly more than $200,000 — an amount, Nicoletti allegedly said, that a certified public accountant calculated as her financial loss. The settlement included her relinquishing any claim to the home. After it was subsequently sold, Stephens claims to have learned during a review of court filings that the CPA's damage analysis actually totaled more than $644,000.

Stephens asserts in court filings that when she raised the issue with him, Nicoletti wrote in an e-mail that she'd been informed about the analysis but that she "must have forgot."

Stephens, in court documents, claims that she had not been told about it at all.

Nicoletti defends the settlement, saying that's what happens in lawsuits. Negotiations occur, a middle ground is arrived at.

"I got her more than $200,000," he says.

Karen Stephens doesn't see things that way.

"My own attorney sold me out," she claimed in a court filing.

The court files reveal two other issues that have inspired her to see Nicoletti as the enemy. One was a check made out to her and Nicoletti from an insurance company for $25,000 as part of her settlement in the Canyon case. Nicoletti cashed that check without her signature or her approval, she claimed in court documents.

Stephens filed a police complaint, but an investigation found no grounds to press charges.

She also discovered what she claims was a "secretly issued" court order from February 2004 giving Nicoletti authority to put a $182,000 lien on the home she owns in Clinton Township to recoup what Stephens, in court documents, calls "bogus" attorney fees. Nicoletti tells Metro Times that the lien, ordered by Judge John McDonald, is to cover legitimate fees, but that he hasn't yet filed it with the register of deeds.

Unable to convince the courts or other autorities that their allegations against Nicoletti were valid, the two have taken their battle to the Internet, posting allegations regarding the lawyer on a variety of Web sites.

Much of what appears online concerns the claims made against Nicoletti by Stephens and Dreilich. But there are also links to other court cases involving Nicoletti that have been copied, scanned and put out there for anyone to read.

There are also YouTube postings drawing attention to a strange court order that has played a notable role in the arc of Marie Dreilich's story.

OUT OF ORDER

In November 2003, just a month after Marie Dreilich and Karen Stephens reconnected and found allies in each other, Dreilich told Nicoletti she would be filing a malpractice suit against him if he didn't return the $5,000 retainer he'd been paid during the case against Viviano. They negotiated, but couldn't reach an agreement.

Nicoletti claims Dreilich began harassing him at that point and sought a sweeping personal protective order (PPO) against her Oakland County Circuit Court.

In attempting to justify the need for a PPO, Nicoletti claimed Dreilich was already mentally unstable at the time she and Roland hired him at the end of 2001.

She doesn't deny her downward slide had begun by that point. She'd been "bombarded" with motions from Viviano's attorney, forcing her to work at a frenetic pace to file responses, she says. And the higher mortgage caused by Viviano's lien was causing a lot of financial problems.

Stress and fatigue were beginning to wear on her state of mind, she says. She also suffered a miscarriage, and says a doctor attributed that to the pressure of all this.

Two years later, claims Nicoletti, she came after him with a vengeance: "All of a sudden, in the beginning of November [2003], I start to get e-mails from Marie Dreilich, saying I've engaged in organized crime, I'm corrupt, she's filing a grievance, she's filing a lawsuit, I've committed RICO violations, you name it. She's sending all these e-mails to my office unsolicited," Nicoletti told Judge Martha Anderson.

Nicoletti, in a subsequent hearing to determine whether the PPO should remain in force, also accused Dreilich of posing as a real estate agent to gain access to his house when no one was home and then leaving a summons outside. He also accused her of "lunging" at him with her car in the courthouse parking lot, but admitted there were no witnesses.

Dreilich, at the same hearing, testified:

"I've sent him two e-mails. This is ridiculous that an attorney can steal your money and then if you ask for it back you get a PPO against you …"

Dreilich said she's never been to Nicoletti's house, and said the Sheriff's Department had legally served the court summons.

That didn't matter. The PPO remained. Nicoletti sent an e-mail to Stephens saying that if she persisted in contacting him that she would be next, just like "your new friend" Dreilich. A copy of that e-mail was subsequently included in court filings.

Even without an order specifically identifying her, Stephens was directly affected by the PPO because of a provision barring Dreilich from not only contacting Nicoletti and his family but also any of his clients, present or former.

That meant Dreilich and Stephens were prohibited from even talking on the phone, let alone cooperating in any legal actions against Nicoletti. They were especially outraged that the order kept them from attending church services together.

"It's a big church," responded Judge Martha Anderson, who issued the order. "They have a lot of different services. Why do you have to attend the same service?"

"Well, how can I even contact her to find out which one she's going to?" asked Dreilich. "That's how ridiculous this situation is."

Metro Times contacted three law professors to ask about the PPO's provision stipulating Dreilich couldn't contact former clients of Nicoletti's. They all said that, given the scenario described, it was at best an odd and overly broad order, given that Nicoletti appears to have never made the claim Dreilich actually harassed any former clients.

"Without clear evidence that she was harassing other clients, such a broad order raises serious First Amendment questions," says Wayne State University law professor Robert Sedler.

Dreilich argued in court that there was only one former client Nicoletti had a real concern about her being in contact with — Karen Stephens.

"She's my main witness in my case of legal malpractice against Mr. Nicoletti," Dreilich testified. "That's mainly the reason for this PPO …"

Stephens made a similar argument. "I know of no law that can prohibit two compliant people to be in public together," she wrote in a filing. "I consider this PPO ridiculous, legally deficient and a complete facade to keep Marie Dreilich and I from being witnesses together."

It wasn't an idle claim. Stephens says she was twice removed from court when she showed up in support of Dreilich.

And Dreilich ended up twice being arrested and jailed because of that PPO.

The first time was in May 2004. She was arrested for being in court with Stephens when Nicoletti made an unexpected appearance. He'd already withdrawn from the suit filed against her by Canyon Construction; Stephens was acting as her own attorney and was in court to argue a motion. Dreilich was there as a witness. She was jailed for one day for violating the PPO.

The second arrest came a month later when Dreilich appeared in court seeking to change the PPO so that she and Stephens could legally remain in contact.

"I'm asking to modify it so Karen and I can attend court together, we're friends, we attended church together prior to this PPO and I don't think he [Nicoletti] has a right to violate our constitutional rights to say that we have to not have contact," Dreilich said. "It's just to protect himself from us testifying for each other. It's absurd. It really is."

When Dreilich asked Judge Martha D. Anderson, who issued the order, the legal justification for prohibiting her from contacting Nicoletti's former clients, the judge responded: "Based on the fact that I signed the personal protection order."

At one point Dreilich asked that Stephens, forced to wait outside in the hall, be allowed to testify. When the judge asked why, Dreilich replied that she wanted Stephens to be able to provide her side of the story.

The reply was Kafkaesque.

"I don't need her side of the story," responded the judge. "This personal protection order has nothing to do with Ms. Stephens."

The judge then chastised Dreilich for making Nicoletti's life "miserable." Judge Anderson also accused Dreilich of having an "obsession about what's going on" and making a "mockery" of the court by repeatedly trying to have the PPO modified.

After being told several times by the judge not to utter another word, and to only nod "yes or no" when asked a question, Dreilich spoke out again to request a change of venue.

The judge responded by summoning a deputy and having Dreilich arrested. She served eight days in the county jail for contempt of court.

It was, says Dreilich, traumatic. Behind bars with people she described as junkies and drunks, she broke down.

"The other prisoners called me 'Baby' because I cried the whole time," she says, laughing about it now but deeply shaken at the time.

And though she laughs, she says she remains scarred by the experience.

FIGHTING BACK

Their encounters with the legal system have caused the two women to become activists of sorts.

Both testified before the Michigan Supreme Court earlier this year when a public hearing was held regarding the handling of complaints placed with the Attorney Grievance Commission and the Judicial Tenure Commission.

And there are postings on Web sites exposing issues associated with mortgage fraud, and legal-system watchdog sites. Stephens is part of a group called Homeowners Against Deficient Dwellings. Much has been written about Nicoletti.

He says the women have gone way too far, writing in an e-mail that he's anticipating legal action against them, and suggesting this paper tread carefully in our reporting of him.

"Will I be adding Metro Times to my libel/slander suit along with Dreilich and Stephens?" he asked in an e-mail responding to some of our queries.

Additionally, he claimed that by reporting on this, Metro Times was violating the PPO's provision stating that Marie Dreilich is prohibited from "publishing" information about him in "any manner." Jail time and a fine could be the consequence if we were found in contempt of court for violating the PPO.

That, however, may no longer be an issue.

Last week, a request from Nicoletti to renew the PPO for another year was denied by Judge Anderson, according to a document e-mailed us by Stephens and confirmed by Anderson's office.

OTHER PROBLEMS

These days, a pair of middle-aged suburban women posting information about him on Web sites might not be Paul Nicoletti's most pressing problem. They're no longer, as Dreilich says, "two loons alone" raising questions about his actions.

And the people he's up against now won't be reduced to representing themselves in court wearing a black rayon jogging outfit, which is Dreilich's customary court attire. It's high-priced corporate attorneys in expensive suits targeting him these days.

One year ago, Nicoletti — in his role as president of Continental Title Insurance Agency Inc. — was named as an alleged conspirator in a $10.8 million fraud case brought by Fifth Third Bank. Fifth Third claims Continental was involved in six of the seven allegedly fraudulent transactions identified in the suit.

That lawsuit involves allegations of a broad conspiracy among mortgage brokers, appraisers, title companies and straw buyers. Bank employees were also allegedly involved. As outlined in court filings, the alleged scam is said to have worked like this:

A house is bought for a certain amount, say $30,000. A crooked appraiser values it at $110,000. A straw buyer is found. A mortgage agent fabricates a credit and employment history to make the buyer appear eligible. A title company turns a blind eye to the irregularities and a mortgage is issued. When no payments are made, the lender is left holding an $110,000 mortgage on a house that's only worth $30,000. And the crooks divvy up $80,000 in illicit gain.

Nicoletti, who denies any wrongdoing, says the bank is at fault because a number of its employees participated in the alleged fraud. He's filed a $75 million countersuit.

Nicoletti initially responded to the bank's requests for information by relying on his Fifth Amendment protections against self-incrimination. He tells Metro Times that he's now prepared to answer questions.

"My deposition was scheduled but was delayed since I sued 13 past and present 5/3 employees for fraud, libel and predatory lending," he said in an e-mail.

Two of his former clients were particularly interested in the news that the bank was suing their onetime attorney.

"Karen called me as soon as she read in the paper about Nicoletti being named in that Fifth Third suit," says Dreilich, unconcerned that she was apparently admitting to violating a court order.

It did matter, however, in 2006. At least that's Dreilich's contention. She claims that PPO made a surprise appearance in a Macomb County courtroom when the fate of her family's home was being decided.

Oddly, one of the key players in that case had problems involving the same type of fraud conspiracy Nicoletti is accused of being a party to.

But that coincidence was still a few years off during the first part of this decade, a time when Marie Dreilich says it became increasingly difficult to function.

BOTTOMED OUT

According to Marie Dreilich and her family, her mental state grew progressively worse after losing the lawsuit to Viviano in early 2002.

Following her 2004 jailing, she hit bottom and stayed there, hiding in her bedroom from the world, curled up with her Pomeranian, Summer.

A big part of her problem, she says, was an inability to accept that Viviano could prevail in a case she has always claimed was illegitimate.

"I'd always believed in the system," she says. "I thought it was supposed to protect people like us. But what I found is that it protects the people who have the money, power and connections."

The family's financial situation grew continuously worse. There were also claims of harassment. In the court file is a picture of Roland holding a decapitated rabbit found in their front yard. It's the most extreme example of what they claimed was an ongoing problem.

Asked why they didn't just pay Viviano the money awarded him, Marie cites a combination of factors. At first they held the hope that a higher court would rule in their favor. And then the combination of higher interest on their mortgage, massive attorney bills and the garnishing of Roland's wages made money scarce. But pressed, she admits that part of the reason was stubbornness.

"I kept thinking that someone would believe us," she says. "I thought that somewhere there would be a white knight who would come to our rescue."

She says she approached law enforcement on every level — county, state and federal — all to no avail.

The cloud of despair and depression hanging overhead grew darker.

After the Dreilichs started missing mortgage payments, the house went into foreclosure in May 2004. Even at that point, they still had six months to "redeem" the property if they could come up with either a new mortgage or a private investor.

This is where an already bizarre story takes stranger twists.

ENTER TAMBURO — OR NOT?

The Dreilichs claim that after the house went into foreclosure and the six-month redemption period began, a mortgage broker named Dennis Tamburo showed up at their door. It's claimed in court filings that Tamburo had learned the house was in foreclosure, and came offering to help them obtain a loan.

"I was in the shower when Dennis Tamburo knocked on our door," she says. "He left his card with Laken, and then I called him."

According to Tamburo, that story is a complete fabrication. He says he had no contact with the Dreilichs between 2001, when he helped them secure an early loan on the Highbury Court property, and 2005, when he was named a defendant in a lawsuit filed by Marie Dreilich.

In that lawsuit, Dreilich alleges:

Dennis Tamburo wasn't a stranger when he contacted them. The Dreilichs had worked with him in 2000 to obtain a mortgage after the lien placed by Viviano caused their original loan deal to go bad. After that, the Dreilichs considered Tamburo an "awesome mortgage guy" who could work miracles. The first time around, everything came off without a hitch, and after that he helped Marie prepare a damage claim showing how much Viviano's lien had cost her and husband Roland.

In 2004, the Dreilichs claim in court documents, Tamburo again promised the Dreilichs that, despite their dire financial situation, he could get them a loan in time to pay off the bank before their redemption period expired. In addition to his commission, Tamburo also wanted Roland Dreilich to do the drywalling for free at the Washington Township home he was then building. Dreilich agreed.

In their version of events, he strung them along, allegedly telling them that he had a "lock" on an alternative financing mortgage and that there was a "100 percent guarantee" it would come through. Then, as the deadline neared, he began refusing to take their calls.

Frantic, the Dreilichs began looking unsuccessfully for another option.

But they hadn't heard the last of Dennis Tamburo.

TAMBURO'S TROUBLES

By the end of 2004 — when the Dreilichs say they were counting on Dennis Tamburo to come through with a loan, Tamburo was already dealing with allegations of fraud leveled at him by his former employer, the mortgage company AmeriFirst.

In a July 2004 complaint filed against Tamburo and his wife, Kristen, AmeriFirst alleged that while Tamburo managed the company's Harper Woods office he had "devised a scheme to ensure handsome profits with very little risk."

According to the lawsuit it worked like this: "The Tamburos purchased properties, sometimes distressed properties, for their own investment. They would then find an interested buyer who might not otherwise qualify for a mortgage. Dennis would use his position with AmeriFirst to ensure that the buyer qualified for the full [inflated] value Dennis and Kristen hoped to receive for the property. Defendants would then sell the properties to their newly qualified purchasers for a substantial profit."

Instead of engaging in the kind of conspiracy that's alleged in the Fifth Third case, the Tamburos, because of Dennis' position as a branch manager for a mortgage company, were allegedly able to largely act alone.

To do so, though, they had to skirt company policies that prohibited its employees from being involved in transactions in which they had an interest.

It is alleged in the lawsuit that the Tamburos disguised their personal interest in property by transferring ownership to a corporate entity just before closing the sale, creating the appearance that the transaction involved a "non-interested third party."

The lawsuit alleges that the Tamburos did this in more than 30 transactions. For 2002, when Tamburo was managing the Huntington Woods office and allegedly defrauding his employer, the couple had a reported income of nearly $350,000, according to their tax return for that year.

But they would soon be facing hard times. To settle the lawsuit brought by AmeriFirst, the Tamburos in June 2005 agreed to pay $300,000 plus hand over an additional $180,000 to indemnify the company for future losses it expected to sustain; $125,000 was paid in one lump sum with the rest parceled out in $10,000 monthly payments. (After initially complying, the Tamburo's began missing payments in April 2006.)

The news of Tamburo's problems would come as a surprise to Dominic Matina, who, along with his brothers, sometimes used him as their mortgage guy (and an occasional golfing partner).

"We didn't know anything about that," he claims. "Our reaction was like, 'Man, oh, man, what a weird thing. What are the odds?'"

Their next thoughts were directed toward speculation about how Marie Dreilich would use that information against them, he says.

He figured she would be able to spin it into part of her conspiracy theory, and that it would seem plausible, because "she always sounds good."

In a phone interview with Metro Times, Tamburo reiterated the assertion made under oath in a deposition that he wasn't working with the Dreilichs in 2004, as they claim.

We also brought up new legal troubles he's having. In October, an online lender named NetBank filed a lawsuit in federal court in Detroit alleging that Tamburo was part of a conspiracy involving dozens of fraudulent mortgage transactions. Asked about that case — which is now in the hands of Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation lawyers — he declined to comment.

SAL'S BACK

When Tamburo disappeared on them (if, that is, he had appeared), the Dreilichs were in desperate straits. With just weeks to go before the redemption period ended, Marie Dreilich found Kelly Esman & Associates in Rochester. She told him about her plight and he offered to help find a private investor. After a few days, that appeared to happen.

At that point they owed $430,000 on their first mortgage; the bank holding a second mortgage agreed to accept $10,000 to sign off on their loan, according to information in court documents. That left only Sal Viviano's court-awarded judgment of $45,000 — and the lien it led to — clouding their title.

A deal was allegedly worked out that would allow the Dreilichs the opportunity to stay in their home, paying $2,000 a month rent with the option of buying the property back at the end of one year — if they could come up with a total of $530,000 then.

At that point, Viviano had already transferred the judgment and associated lien to his business partner and longtime friend Dominic Matina. That lien, says Esman, was the only sticking point.

According to Esman's sworn affidavit, this is what happened:

Even though Viviano was no longer the lien holder, Matina directed Esman to deal with him. Esman offered $5,000 to sign off on the lien.

"Salvatore Viviano very angrily responded that he would not take less than $100,000, that it was his deal, that he was going to 'freeze out' the Dreilichs and declined to sign off on the judgment."

Esman eventually raised the offer to $10,000, explaining that if the bank took the house in foreclosure, Viviano would collect nothing.

"Mr. Salvatore Viviano kept contacting me and proposing different deals insisting that he was going to 'freeze out' the Dreilichs from obtaining their home," wrote Esman. "I refused to consider any of his options. That is when Viviano started to make numerous accusations regarding Marie Dreilich. These comments included that 'she is nuts' and that 'she is going to blow the house up if she ever had to leave.'"

Esman described Viviano's actions as "relentless, threatening harassment ..."

Dominic Matina recalls a different scenario.

"No one interfered with no one," he says. "She [Marie Dreilich] just wanted to keep living in that house for free."

Wearing work boots, paint-splattered jeans and a sweatshirt to ward off the cold while on a job site, he describes himself and his brothers as hard workers. He points to his father sweeping up at the current job site rehabbing a ranch house in Clinton Township.

"This is what I do," he says. "I'm not out ripping people off."

In fact, he tells Metro Times that, as the redemption period was ending, those on what he refers to as "our side" of the case made the Dreilichs an offer he says would have allowed them to stay in the home and eventually buy it back for $500,000. It was an offer he says was repeated after his "side" gained title to the property.

"My brothers would have been willing to let it go for what they had into it," he says.

Marie Dreilich acknowledges that those offers were made, but in court documents alleges that when there was an opportunity to make good on that promise, a deal never materialized.

PAPER TRAIL

In 2005, Marie Dreilich filed what's known as a "quiet title" lawsuit in an attempt to regain ownership of the house the family lost earlier that year but continued to live in without paying rent. A bankruptcy filing and then initiation of the lawsuit stalled eviction.

In the 2005 suit (which was eventually amended to include Roland), the Dreilichs claimed that the title to the property was in dispute and the court needed to decide the matter. The suit alleges efforts to obtain their house constituted a "conspiracy to defraud."

That same lawsuit also accused Dennis Tamburo of committing fraud for his alleged role in the deal.

The case delved into the tortuous history of what the Dreilichs planned to be their dream home.

The Macomb County courts became involved when Salvatore Viviano placed a lien on their property and filed a lawsuit against them using the name of a company that didn't exist. He claimed they owed him nearly $50,000; they alleged he was trying to get paid for work that wasn't done and materials that weren't supplied.

Viviano won the suit and, after being awarded a judgment, placed a $45,000 lien on the Dreilichs' home.

A year later, in May 2003, he transferred the judgment to friend and business partner Dominic Matina for $1, according to a copy of the transfer document contained in the court file.

Matina tells the Metro Times that Viviano simply gave him the right to collect the judgment because there was no expectation anyone would get the money. And there's nothing in any court record showing that either Salvatore Viviano or Dominic Matina ever benefited from that judgment or the associated lien.

What did happen, according to court testimony, was that two people close to both men put up the money to buy the Highbury Court property from the bank for $429,000 — an amount close to what the Dreilichs owed on the house — in January 2005. At the time, according to court documents, the estimated market value of the home was listed as more than $700,000.

The two men financing the deal, according to court testimony, were Sal Viviano's brother, Paul, and Dominic Matina's brother, Salvatore. But instead of having that transaction occur under their names, title to the home passed to the allegedly "non-existent" Matina Construction Inc., the Dreilichs claimed in court documents. (According to the copy of a deed on file in court records, the company listed its mailing address as the Highbury Court address; the Dreilichs were still living there at that point.)

Although Matina Construction Inc. does not seem to exist — Metro Times did not find it listed in the state of Michigan's online database of corporate filings — a similarly named company, Matina Construction Corporation Inc. is a legal entity. Its president is a third Matina brother, Gaetano. According to court testimony, he was originally supposed to be a partner in the deal, but backed out after the home was purchased.

(In the original 2000 case, Gaetano Matina, in the role of expert witness, provided a schematic that Salvatore Matina used to bolster his claim regarding the number of bricks used in the Dreilich's home.)

After title passed from the bank to Matina Construction Inc., Paul Viviano and Salvatore Matina then worked with Dennis Tamburo to obtain a $550,000 loan, the men testified.

In court, Salvatore Matina admitted the loan application — signed by them and submitted by Tamburo — contained information that wasn't true. Among those inaccuracies was the claim that he and Paul Viviano had been living in the Highbury Court house since 2003 — four years before the Dreilichs would be finally evicted. Salvatore Matina was also identified as the president of Matina Construction, a fact he admitted was not true. He said on the witness stand that he didn't know how the mistakes got into the loan application.

Asked by Metro Times about the false claims, Dennis Tamburo called them "typos."

The lawyer representing the Vivianos and Matinas, and the lawyer representing Tamburo, argued that what happened after the property was sold by the bank was irrelevant. By that point, the Dreilichs no longer had legal interest in the property, and therefore had no standing.

Judge Mary A. Chrzanowski agreed. Furthermore, the judge several times told the Dreilichs she was not going to lose sight of the fact they had lived in their home for the past two years rent-free. (Dominic Matina says the free ride had actually started even earlier, when the house first went into foreclosure.)

The judge raised the possibility that the Dreilichs be allowed to buy the property back, suggesting that $550,000 would be a fair price given the expenses sustained by Matina and Viviano. But with their credit rating trashed and a bankruptcy on their record, there was no way the Dreilichs could come up with that kind of mortgage.

Noting that she failed to see any evidence of some "grand conspiracy," Chrzanowski advised the Dreilichs that it would be in their best interest to settle the case; otherwise, she implied, they would very likely end up paying a substantial settlement to the Matinas and Vivianos.

Certainly, Marie Dreilich's testimony failed to convince the judge that her conspiracy claims held any merit. On the stand, she faltered badly.

"Her own attorney was questioning her and she couldn't answer questions," says Matina. "Our attorney didn't even need to ask anything. That's the way it is with her."

Marie Dreilich admits she stumbled badly at a crucial juncture, saying, "You can just see me shrinking up there on the stand, getting lower and lower as it goes on."

Matina says the reason for her failure is obvious: She had no real case to make, and couldn't substantiate her allegations.

Dreilich says she was under extreme duress, and that the judge's repeated reminders that she wasn't going to forget that the Dreilichs had been living in the house rent-free were an ill omen that caused her to melt down.

There was one other factor: Earlier in the trial, she asserts in a court filing, she saw the PPO issued at the request of attorney Paul Nicoletti in an Oakland County court in the hand of Sal Viviano's lawyer. Stephens, who had come to be a witness, says she too saw the document. Both women say seeing the PPO unnerved them.

If it was in that courtroom, the document was never brought to the judge's attention and no attempt was made to keep Stephens out of the courtroom.

In the end, the Dreilichs heeded the judge's advice and agreed to settle. They gave up any claim to the house. Tamburo was ordered to pay the Dreilichs' lawyer $2,000. The Vivianos and Matinas got clear title to Highbury Court. They also got stuck with all the attorney fees that came with fending off what was a last-ditch effort by the Dreilichs.

The Dreilichs were evicted in January 2007. The house sat on the market for 10 months before it sold in October.

LIENED ON

Just before she filed her lawsuit against the Viviano brothers, the Matina brothers and Dennis Tamburo, Marie Dreilich made what even she admits was a terribly bad move.

After repeatedly trying to get the Macomb County Prosecutor's Office to take up a fraud case against Sal Viviano, and being told, she claims, that problems involving disputes over liens are matters for civil courts, she took it upon herself to file six liens under the name of her husband's company on property owned by the Vivianos and Matinas.

She was arrested and spent another night in jail. Her daughter, Laken, was there when five police cars rolled up to the house on Highbury Court to take her mom away. When Laken attempted to come to her defense, says the teen, the cops threatened to take her to a foster care home.

Early in the case Marie Dreilich agreed to plead guilty to a misdemeanor charge being offered by the Prosecutor's Office instead of a felony. However, she changed her mind and decided to take her case to a jury.

Asked by Metro Times why she would risk serving 18 years in prison if convicted on six felony counts of filing fraudulent liens, she goes back to the original case involving Sal Viviano in an attempt to explain.

Time after time, in one court proceeding after another, she has put on the public record her assertion that Viviano committed fraud in that first case. Even though the court sided with him, she has relentlessly attempted to have what she claims is that initial wrong addressed.

"Nothing was done to him, but I have this on my permanent record? No. I decided I was going to keep fighting it."

Even though it was clear at that point that she'd broken the law?

"Yes," she says. "I thought I could make the case that I was the victim of selective prosecution."

She reasoned that Viviano wasn't prosecuted for what she alleged was fraud after he filed the lien. Why, she reasoned, was it right to prosecute her? It didn't matter to her that in Viviano's case work had actually been done and the dispute involved the amount of money due while in her case there was not even the pretense of justification.

Her refusal to see that distinction is telling. But, looked at from another angle, it could also be read as a reflection of her absolute belief that she had been wronged by Viviano from the outset.

A trial was set for June 2006, and a jury selected. After she claimed jury tampering, there was again talk of a plea deal.

She claims to have again received an offer to have the charges reduced to a misdemeanor, but only if the family left the Highbury Court home, according to court filings. At that point Salvatore Matina and Paul Viviano had purchased the home, and they were having trouble getting the family out.

With the quiet title case still pending — and the case offering the hope that she could win the house back — she refused to accept the misdemeanor charge, and instead pleaded no contest to one felony count. She was put on one year's probation.

Matt Sabaugh, the assistant prosecutor handling the case, tells Metro Times that issues involving that civil action would not have been part of the criminal case. He also says that any misdemeanor offer would have been "off the table" at that point.

Dominic Matina, who was in court and conferred with the prosecutor handling the case as he shuttled back and forth behind closed doors negotiating a plea deal in the summer of 2006, also says Dreilich's claim is untrue.

Dreilich is now trying to have the felony plea overturned. With that black mark on her record, she says, finding a decent job has been impossible.

In an appeal filed by a court-appointed lawyer, it is argued that Dreilich believed that putting the liens on property without just cause would be a civil matter. The reason for that belief, it is argued, was her assertion that the Prosecutor's Office allegedly told her that lien cases are a matter for civil proceedings.

Her appeal has yet to be decided. Multiple lawyers have been assigned to her case, only to withdraw.

As for her probation, that should have ended in June. But there's a disputed fee that hasn't been paid, resulting in an extension. Until recently, it had also been extended for another reason: Dreilich had attempted to convince the real estate agent handling the sale of the Highbury Court property that there could be problems with the title. Margaret DeMuynck, chief of the white collar crime division of the Prosecutor's Office, asserted in court that contacting the real estate agent amounted to "indirect contact" with the Vivanos and Matinas, and that was a probation violation. A judge agreed and ordered Dreilich not to interfere. She has apparently abided by that order.

The home, says Dreilich, was sold in October. She says it still remains vacant months later, and wonders what is happening with it. A call from the Metro Times to the purported owner was not returned.

With that sale, Marie Dreilich says she finally accepts the fact that her home has been lost and there is no hope of getting it back.

It's a reality — something she admits to not always being able to discern over the past eight years. But, she says, she's better now than she has been.

Following her arrest on the felony lien charges, she sought counseling with a therapist associated with her church and took anti-depression medication for a while. Lately she's been spending a lot of time with Laken going to cheerleading competitions. So some normalcy has returned to her life.

But money problems continue, especially with the construction slowdown making it difficult for Roland to keep putting in the kind of overtime he's worked most of his life. Not long ago, he was on the verge of leaving for the Southwest, but landed a job here at the last minute.

Even so, Marie's car was just repossessed.

She still cries easily and becomes unnerved at times when talking about this case, so she is not completely well. She equates what she's going through now as recovery from a kind of traumatic stress.

"It's been eight years of hell," she says. "Every day is a struggle to try to rectify what happened because I still believe that Roland and I were such hardworking and honest people that didn't deserve this."

The other view is that offered by Dominic Matina: Marie Dreilich is a spinner of grand tales, and the real victims in this are all those she unfairly accused of wrongdoing.

The court decisions are on his side in that regard, and on the side of his friend and partner, Salvatore Viviano.

As for Marie Dreilich, this is what she has to say:

"I know that I did go crazy during all this. And I also know that not everyone I said was in this conspiracy against me really was. But that doesn't mean I was wrong about all of it. And if nothing else, I have it out there on the public record for people to see."

Wherever the truth lies, those records chronicle an eight-year odyssey that's extracted a price that can't ever be fully measured.

And it all began with something as mundane as a dispute over bricks.

Curt Guyette is news editor of Metro Times. Send comments to cguyette@metrotimes.com or call