Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Violet Ikonomova

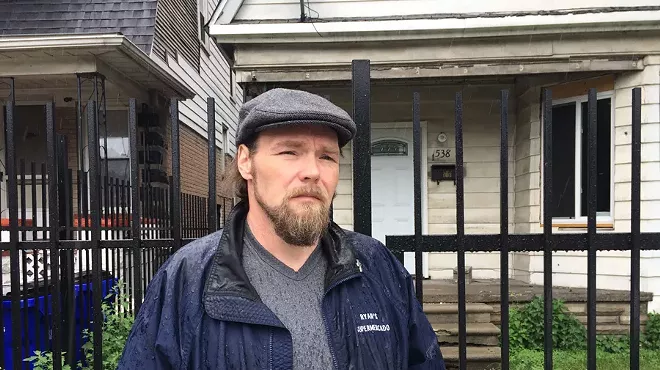

Foreclosed homeowner Kevin Dickerson, who lost his home in the Wayne County treasurer's 2017 auction, now awaits eviction. Thousands more Detroiters could be headed for the same fate.

The annual wave of displacement that’s been devastating Detroit neighborhoods for nearly a decade is rolling right along, with this coming year shaping up to look much like the last.

About 36,000 Detroit properties that are at least two years behind on their taxes have received foreclosure notices ahead of next year’s tax auction, according to the Wayne County Treasurer's Office. Last year, the office says about 39,000 properties received such notices ahead of the tax auction that took place this fall.

Though Wayne County officials do not yet know how many of the of the foreclosed properties are homes where people live, Detroit-based data mapping company Loveland Technologies says that, during the 2017 auction cycle, 32,000 properties turned out to be occupied. Some 2,000 of those homes went on to be entered into the fall foreclosure auction to be sold to the highest bidder. The majority of remaining homeowners were able to avoid the forfeiture list by making payment arrangements with the county.

Residents currently facing foreclosure will have to pay their tax bills or make plans to do so by spring. About 36,000 Detroit properties are reportedly on payment plans with the treasurer for tax debts.

As the treasurer’s office prepares for next year’s occupied home sale, some tax-foreclosed residents whose homes were sold in September and October are still anxiously awaiting eviction.

Kevin Dickerson, his wife, and their two teenage kids are among the hapless Detroit residents whose homes were sold out from under them. The Dickersons, having been outbid in their effort to buy back the Conant Gardens bungalow that Kevin’s grandma had built in 1950, are now living in their home on borrowed time: The investor who bought the house for $8,500 is waiting to hear whether the family is willing to purchase it. But even at the sale price, the home is unaffordable for the Dickersons, who live off mother Arnetia’s $9-an-hour job.

In a phone call this week, Kevin Dickerson explained that he and his wife are using the days until their inevitable eviction to save up for a rental in the suburbs.

“This I’ll tell you for sure — I can definitely say that when we move, we won’t be movin’ in the city no where,” Dickerson says. “Why would I stay in the city when there’s no good schools, you call the police they don’t come, you call an ambulance they take forever to come… and they charging us for taxes like we stay in the safest city in the country.

“[Foreclosure] is not something nobody should go through staying in the city until they make some better arrangements for the people that live here.”

The impetus for Kevin’s call, however, was not to brief us on his situation, but to share his discovery of an eye-opening video regarding Detroit and Wayne County’s tax foreclosure scheme.

The video, published last week by Vice News Tonight, clearly conveys the forces propelling the epidemic that saw an estimated one in four Detroit properties foreclosed between 2011 and 2015. It describes how the Detroit assessor's office failed to properly reassess home values in the wake of the collapse of the housing market, leading to what one study has described as the over assessment of the majority of Detroit property tax bills between 2009-2015. And it portrays a county that financially benefits from the interest added to late-paid taxes.

“The way you make money … say I buy the house you’re in for $500, I’m now the new owner and I’m offering you a deal to stay there,” Stevie Hagerman, an investor with Brick Home Management, told Vice News Tonight. “We sign a 12-month lease, you pay me $500 the first of the month, in one day we’ve gotten our money back and after that, it’s profit.”

Caught in the middle, of course, are the often low-income folks whose homes are taken. Vice News Tonight reported that Hagerman bought the home of a social worker named Judy Kelley, and offered to let her continue to live in it for a fee.

But Kelley, much like Dickerson, isn’t sure about sticking around Detroit after her ordeal.

"Do you think you'll ever have a chance to own property in Detroit again?" reporter Antonia Hylton asked Kelley.

"The question should be, would I want to,” said Kelley. “I'm not sure."

“I’m starting to put the story together what everyone is doing,” said Dickerson. “You hear people say they’re trying to take the city, [but] no, actually it's a business.”

And he’s sort of right. The county, which buys the city’s unpaid tax debts, managed to stave off bankruptcy a few years ago thanks to the interest and fees it collected on late-paid taxes. According to an expose published by Bridge Magazine last spring, the county borrows from lenders at interest rates of up to 5 percent to the buy the debts, then collects administrative fees of 4 percent and interest rates of up to 18 percent on late-paid taxes — a substantial return on investment. The revenues derived from this practice are included in county budget projections through 2019.

High interest rates are what, ultimately, led Dickerson to lose his home. He was on a payment plan for unpaid taxes in 2013 when, he says he realized that, by the end of the year, his monthly payments of $300 had only covered the interest on what was owed. The next year, with both him and his wife out of work, the couple applied for a poverty exemption to eliminate their tax bill, never heard back, and assumed everything was squared away. They were wrong.