For Banned Books Week, Michigan advocates take a stand against censorship

Ann Arbor bookstore Booksweet is doing their part to make change and spread awareness about book bannings in the state

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

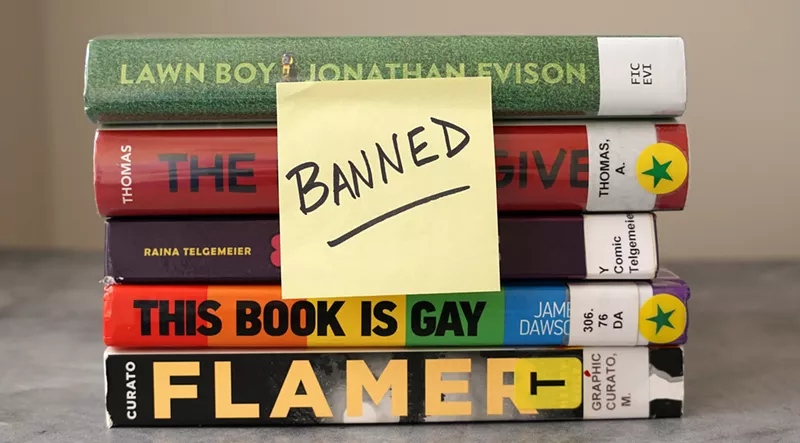

Book bans are no longer a distant problem but an alarming reality in the United States. According to research conducted by PEN America, instances of book banning increased 33% nationwide from the 2021-22 to 2022-23 school year.

With Michigan caught in the crossfire, concerned parents, educators, and bookstores are joining forces to protect the diversity of voices found in the books on local shelves.

The annual Banned Books Week takes place from Oct. 1-7, celebrating the freedom to read and uniting book lovers to address the issue of censorship. Booksweet in Ann Arbor is one Michigan bookstore fighting for change, preparing to host a Banned Book Social from 5-8 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 7 to spread awareness about book bans locally.

Owners Truly Render and Shaun Manning describe themselves as “life and business partners,” and have a lot of knowledge on book bannings and advocate heavily for social justice issues at their shop. The pair hopes that the upcoming open house-style gathering, which will feature a diverse lineup of speakers, story sessions, and family-friendly activities, will allow people to have a fun time while learning about a not-so-fun problem.

“We’ve been open since August of 2021. If you look at book-banning data, that's just the school year where book bans were really heating up in intense amounts. Book bans have always been a problem, but it was largely seen as pretty un-American until that year, in which it just exploded,” Render says. “That’s part of why in year one of business we wanted to do something to address it. It was highly relevant and it was just right there in need of community conversation.”

In 2022, the pair started a Banned Book Club to meet with community members year-round in a discussion about books that have been banned locally.

“One of the things that we really wanted to stress is it’s not a ‘somewhere else’ problem. This is here, it’s happening in our state, it’s happening in our county. If it’s not happening at your school or at your library yet, it’s coming,” Manning says. “We really wanted to emphasize that this is something we all need to be ready for and know how to confront and push back against as it affects our communities.”

Booksweet’s Banned Book Social will also serve as a sales push, as a percentage of profits made will be donated to PEN America, a national program that focuses on tracking and reporting book bans happening in K-12 public education, building public awareness, and providing analysis on a national level through local advocacy and outreach efforts. The organization has chapter cities all across the country, including one in Detroit, that coordinate with various grassroots groups.

Fortunately, Michigan is not Florida, where 40% of all book bannings in the country happened last year, though there have been some intense examples of book bannings, or at least a push for them, in our state.

In Dearborn last November, Michigan Republicans and a group of Muslim advocates protested Dearborn Public Schools’ refusal to remove LGBTQ+ books from libraries.

After months of school board meeting debates, at least two popular books — Push by Sapphire and Red, White and Royal Blue by Casey McQuiston — were permanently removed from the schools’ libraries after being deemed inappropriate.

This past June, a Ferndale library was also targeted by a bigoted “Hide the Pride” campaign against LGBTQ+ books. Many of the library’s novels that discussed topics surrounding transgender issues and characters were pulled from the shelves.

Those are just two of the 39 recorded instances of book bans across the state from July 2022 to June 2023.

Overwhelmingly, book censorship targets novels that discuss racial and queer issues, so for students of color and students who identify as LGBTQ+, book banning is even more detrimental.

Cathy Fleischer of Everyday Advocacy, who will speak at the Booksweet event to share strategies for educators on how to ensure that challenged books remain accessible in schools, quoted the metaphor by Rudine Sims Bishop, who said: “Books can serve as mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors.”

“We read these books because they might mirror our own experiences and also they’re windows into somebody else’s experience and sliding glass doors because you can go back and forth between the two,” Fleischer says. “So many kids have never seen their own lives or their own experiences in the books that they have been asked to read in school, so they feel left out of all those conversations. Other kids who are white middle-class kids are at the center of so many books, and so when they get a chance to read about people who might be different from them or might have some things in common, but not other things in common, they can start to understand people’s experiences differently.”

Fleischer says that being able to have these conversations in the classroom with professional educators is important to giving children of all backgrounds the opportunity to understand people who are different from them.

After teaching high school and college for decades, Fleischer became more interested in instructing teachers how to create change through advocacy in their everyday lives. She began this work by conducting workshops and webinars, then started working with people like Sabrina Baeta from PEN America who know a lot about young adult literature and book banning. Fleischer says that she and Baeta recently did workshops with middle and high school teachers in Ann Arbor, having them think about a time when a book made a difference in the lives of a kid that they’ve taught.

Baeta, a Freedom to Read Program Consultant at PEN America, handles the research and data analysis for the K-12 public education book-banning report and does some of the outreach and advocacy work that the organization has around stopping book bans, including working with retired professors like Fleischer and collaboration with local bookstores.

“So many kids have never seen their own lives or their own experiences in the books that they have been asked to read in school, so they feel left out of all those conversations.”

tweet this

“Booksweet is a wonderful partner. I’ll do outreach with them either through their Banned Book Club, which is an amazing group, doing presentations and building public awareness,” Baeta says. “I also coordinate with some other advocates on the ground here … mostly leading presentations around the community, and helping resource different efforts in the Ann Arbor, Ypsi area.”

Baeta says many people in Michigan are unaware that book banning is an issue in the state, urging them to get involved locally and less caught up in the national landscape of the problem.

“[Michigan] actually [is] top five in banning by the number of districts that have book bans, so this is an issue here and it’s actually an issue that’s instigated by a vocal minority that’s pushing for the book bans, and that means it can happen in any district,” Baeta says. “It can happen at the local level anywhere, so growing that public awareness and having people already be equipped to be able to prevent book bans has been most of the effort here in Michigan.”

It’s not just about the books though, Baeta adds — it’s about the communities the books represent and the stories that the books share.

“It’s not an unpopular opinion to love books, and I think books and librarians have, in one way or another, changed the lives of many Americans, whether you’re from Michigan or from anywhere,” Baeta says.

Opening the Booksweet event will be Ohio-based author, Aya Khalil, reading her debut 2020 children’s book The Arabic Quilt. The novel is loosely based on her experiences as an Egyptian-American in the U.S. The book won a few awards and honors when it first was released, and then in 2021, Khalil found out it was on a banned list along with dozens of other diverse books in a Pennsylvania school district.

“I was really upset because Arab Americans are so underrepresented in this industry, I think we're less than like 0.5% of the publishing industry,” Khalil says. “I was surprised because it’s a book about friendship and inclusion and just being proud of who you are.”

Shortly after her book was banned, Khalil’s publisher reached out and asked if she wanted to write another book. Her second book is titled The Great Banned Books Bake Sale, and includes the same characters by the same illustrator. In the book, when the main character tries to find Arabic stories for her grandmother who is visiting and she can’t, she’s shocked. So, an entire community of teachers, librarians, and classmates protested and worked together to plan a bake sale to raise money to buy more banned books to put in little free libraries around town.

“It goes to show you that kids are powerful and they can use their voices,” Khalil says. “I’m excited to share more about my story and just talk to the people [at Booksweet] about how harmful book bans are and encourage them to do the things that the kids did in the book, buy more of the books, and support those authors.”

She feels that there should be an open dialogue about the issue between parents, children, and educators, and hopes her books help with that. Khalil says that she and her three kids, who are 10, 8, and 4, are always at the library, and she wants them to have the freedom to read the books they want to read and the books that represent them.

“The thing is, if there’s a book that I don’t feel like they should be reading, that’s a discussion between me and my own kid, it’s not my right to even ask the library or district to ban the whole book,” she adds.

Being a teacher for so long and working with so many teachers still, Fleischer says that she knows how many unique stories educators see during their careers, and that there are definitely many instances where reading can change the lives of a student.

“Lots of books that are diverse books or intersectional books or books that deal with subjects that maybe sometimes some adults are uncomfortable with, when kids have a chance to read those books, it can help make a difference,” Fleischer says. “We’re trying to help teachers think about ways that they can rely on the stories that they know, and to try to shift that into themes and values in order to frame an issue in a way to talk to other people.”

Even when books aren’t completely banned yet, some teachers begin to censor themselves out of fear of how parents and other educators may feel, but Fleischer hopes to help them do the opposite.

“I think it’s important for teachers to think about how they can proactively help others understand why they might want to include these books,” Fleischer says. “I think that right now, we’re still in a place where we could do some of this work proactively to really try to help others understand why teaching these books is important and why having them in schools and having them available to kids who are curious and want to learn more about these issues is so important.”

Fleischer says that the easiest way to spread awareness of the issue is through casual conversations, such as ones with the parents of your child’s peers. “So much is learned about education on the sidelines of the soccer field,” she says.

It’s important for parents and teachers to do the work to educate the community at schools and find others who have the same advocacy mission.

“We talk about in Everyday Advocacy, how to do things in ways that are smart, safe, savvy, and sustainable. The way to do it safely is to find allies and to really do this with other people, so you’re not that teacher who’s just alone in trying to make change,” Fleisher says. “It’s important to have allies, the allies can be in the form of parents or school board members or community members, so you’re doing this together as a group.”

Some ways that Fleischer suggested is for teachers to have parents in to read and discuss books together or have students talk about the books that have impacted their lives.

“K through 12 public education is instrumental in any democratic society, so banning books, especially in that context is just un-American,” Baeta says. “Students are counting on their public schools having the resources and materials they need to succeed. Having them part of public education or any education is being able to view the world as a pluralistic society and being able to critically engage with different viewpoints, so banning content based on certain viewpoints, or wanting to silence or censor certain views, just goes against the concept of public education.”

Baeta urges people to focus on their own individual districts by going to school board meetings, speaking with teachers and librarians, and writing letters to state representatives advocating for their personal views on the subject.

At Booksweet’s Banned Books Social, nonprofit organization Red, Wine, & Blue will lead a workshop on effectively voicing concerns and opinions at school board meetings, library board meetings, and other public forums. Also, throughout the event, attendees will have the opportunity to write letters encouraging representatives to safeguard students’ freedom to read in U.S. public schools and libraries.

“Get involved now when you can proactively say ‘No, that is not our community standard. We want these books, we want these diverse stories. We want to critically engage with these difficult topics,’” Baeta says. “It’s very hard to instigate change, but on a local level, you can be the instigators who are causing the book bans or you can be the defenders who stop them, so everyone does really have the power to step up and make a large impact in their community.”

Subscribe to Metro Times newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter