'Massive loopholes': No guaranteed savings, redlining continues in new auto insurance law

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Last week, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and Republicans struck a bipartisan deal that passed the Senate and House by wide margins.

It sailed through the Legislature partly because the GOP, auto insurance lobby, and Whitmer administration assured lawmakers and the public that while the legislation dismantled mandatory lifelong protections for accident victims, it would lower rates and end redlining.

“The deal: guarantees rate relief for every Michigan driver … and removes the ability of insurance companies to discriminate based on non-driving factors,” Whitmer wrote in statement.

However, that's untrue. Lawmakers who voted against the bill note that it doesn’t guarantee rate reductions and could lead to rate increases for some motorists; doesn’t end redlining and allows insurance companies to continue charging more to residents in Detroit and other urban areas; and eliminates mandatory lifetime protections the state provided for those who got in serious car accidents.

“People say ‘Well we got something for it — we ended redlining, we are saving money.’ That’s a false narrative,” says Rep. Yousef Rabhi (D-Ann Arbor), who voted against the bill.

He says the plan is in many ways similar to those that the GOP pushed and a Democratic minority in the Legislature successfully blocked for eight years while former Gov. Rick Snyder was in office. In the end, Republicans got most of what they wanted while Democrats got few of the demands they had made for the last eight years.

While the bill is presented as a bipartisan compromise, critics say that really means Democrats gave in to Republicans on the most important issues, which is more of a “loss” than a “compromise.”

In a statement sent to Metro Times, Sen. Jeremy Moss (D-Southfield), who voted against the bill, stressed that it “does not provide equal coverage to all motorists; address rate relief beyond the PIP line of your bill; or prohibit discrimination against specific communities.”

Rep. Sherry Gay-Dagnogo of Detroit acknowledged there were some improvements to the legislation, but told The Detroit News that there’s “still not enough lipstick on this pig.”

How did it pass? The statements made by Whitmer, the GOP, the auto insurance lobby, Democrats backed by the auto insurance lobby, and other politicians seemed designed to mislead the public and pressure politicians to support the legislation. Lawmakers who voted against it say the negotiations went on behind closed doors and the bill was only delivered to lawmakers hours before a vote.

Meanwhile, billionaire Dan Gilbert threatened to launch a petition drive to put a similar plan on the ballot in 2020, which some say created additional pressure.

“Five days after a benevolent billionaire said ‘get to work,’ we jumped," Rep. Isaac Robinson (D-Detroit) said in a floor speech, accusing Whitmer of working on Gilbert and corporate interests’ behalf.

No guaranteed savings

Rabhi says there are no guaranteed savings because the law only regulates the personal injury protection portion of an insurance policy.

Auto insurance companies are able to increase the collision portion of the policy or create new categories in it.

“All this legislation regulates is the PIP line,” he says. “There’s no guarantee Michigan residents will see a rate decrease at all.”

The law also requires the PIP line to go down on average across the state, to the degree it's deemed practical by the insurance companies.

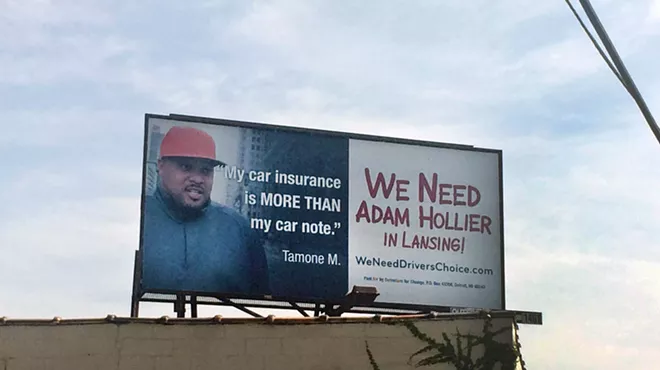

Redlining continues

The law does bar insurance companies from using education, occupation, marital status, zip codes, and other discriminatory measures for rate setting. But Rabhi characterizes the changes to redlining around geography “a semantics issue.”

The law no longer allows insurance companies to use zip codes. Instead, it allows them to redline based on “territorial” rating.

Rabhi says that means insurance companies can now charge more based on which city, census tract, city council district, state representative district, and other territories a motorist resides in.

Similarly, the new law bars the use of credit scores in determining rates, but Rabhi notes that insurance companies don’t typically use credit scores. He says there are multiple other credit products they buy from credit agencies to determine scores, and those aren’t banned.

“There are massive loopholes,” Rabhi says. “This allows insurance companies to redline. They used the semantic game to play people on it. People in Detroit could end up paying more, and Ann Arbor and other communities could end up paying less.”

In the Senate, Sen. Jeff Irwin (D-Ann Arbor) proposed an amendment that would have strengthened the rules around redlining, but it was defeated along party lines.

“The bill prohibits insurance companies from using zip codes, but zip codes aren’t the only geographic territory insurance companies could use to set rates and spike cost in certain neighborhoods,” Irwin says. “[This legislation] does not get the job done, and we still need improvement to the insurance codes that would prevent discrimination.”

He notes that the legislation does allow the state to reject rate increases proposals submitted by insurance companies, and an insurance commissioner appointed by Whitmer will consider the rates.

However, the insurance commissioner can only reject rate increases if there’s “no rational basis” for it, a term Irwin says is one of several in the law that could potentially weaken protections for consumers.

“There are some words in there that make it harder for the insurance commissioner,” he says, but adds, “there will be additional eyes on process, so it will be somewhat difficult for them to play too many games.”

Catastrophic coverage ended

Michigan is the only state in the nation that has mandatory lifelong coverage for auto accident victims. While motorists can still buy unlimited coverage under the new legislation, Rabhi says that not requiring all drivers to pay into the catastrophic fund that covers accident victims’ lifetime care will eventually lead to its collapse.

For those who choose not to pay for unlimited coverage, auto insurance companies will cover between $50,000 and $500,000 of the cost of care. But that’s a small amount of coverage for an accident that leads to serious injuries.

A motorist's health insurance will kick in after the insurance covers the first $50,000 to $500,000, but only the very best plans offer sufficient long-term coverage. That means the accident victims who need the financial coverage the most — someone with a brain injury or who is paralyzed, for example — will likely end up bankrupted or unable to pay for the necessary care, Rabhi says.

“It’s hard to think about all the folks who are not going to have the resources to take care of themselves, who will be paraplegic, quadriplegic,” he says. “Some people will do well in the new system, but a lot of people, especially people who are low income, will not."

Moreover, while the old law pays for accident victims no matter who was involved, including pedestrians or cyclists, the new law does not, Rabhi says. If a pedestrian or cyclist is hit by a car then they will no longer be covered by the state.

'Behind closed doors'

Rep. Kyra-Harris Bolden (D-Southfield) said in a Friday statement that the bill was quickly pushed through by Whitmer and Republicans, and “received no public hearing, no testimony, no fiscal analysis, and was only presented to Michiganders mere hours ago for review.”

“This plan does not effectively prohibit discrimination for non-driving factors or close loopholes left for insurance companies to exploit,” she added.

Rabhi agreed, noting that the “dealmaking process was very much not inclusive of the public."

“It was not an inclusive process for the Legislature, for the public, and it was done behind closed doors, which is problematic, especially when you're ending a system that’s been in place for 40 years,” he says. “I think that a lot of my colleagues in the House were unhappy with the way the process went down.”

On the Senate floor, Irwin said the bill "was being rushed through the floor process and I think that’s indicative of the product we have here in front of us."

Rabhi says there also seemed to be pressure to vote for the bill because the misleading information pushed by the bill’s backers led people to believe it would guarantee lower rates and end redlining.

“Unless you dissect the bill a little, then you won't see how this is being misrepresented," he says. "Then there was some fear of political consequences, voting against the governor and voting against ‘lower rates.' I had the sense that people felt a lot of pressure to vote for it.”

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.