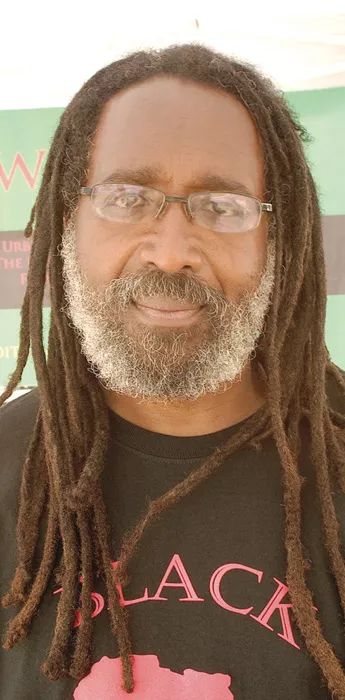

A resident of Detroit’s west side, Malik Yakini, 58, is head of the nonprofit Detroit Black Community Food Security Network. He’s an activist and educator about food justice issues who has been honored by none other than the James Beard Foundation. His group runs D-Town Farm in Rouge Park, the largest farm in the city of Detroit. Yakini’s group is also the lead organization in creating the Detroit Food Policy Council, which tries to push food systems policy in a positive direction in Detroit.

MT: What’s your advice for newcomers?

Malik Yakini: My advice to newcomers would be to take the time to learn about the more than 50-year-old struggle of Detroit’s African American community for empowerment and self-determination. And this is important, because many of the newcomers coming to Detroit are young whites, who, while they may be well-meaning, if they’re not aware of this decades-long struggle for black empowerment, they may function in a way that is oppositional to that legacy.

MT: What might the practical ramifications of that be?

Yakini: What we might see is enclaves of newcomers in neighborhoods that are highly capitalized and have lots of development, have amenities like bike paths, but do not insist that the rest of the city, the neighborhoods where the majority of the African American population lives, have those same resources. And so they can play into this narrative that is being played out in Detroit that is the story of two Detroits, where you have one, which is highly resourced, has lots of development, is mostly white, and then you have the rest of us.

MT: Is it something you hear widely discussed from, let’s say bars and barber shops?

Yakini: Well, I’ve had dreadlocks for almost 30 years, so I don’t really frequent barber shops [laughs], but in the circles I run in, yes, it is being discussed. Even most recently, there was discussion just yesterday about busted water mains and about how there was one that busted by Campus Martius, and how quickly that was repaired, but there’s one on the city’s west side, which has been flooding the streets for more than two weeks, and there’s no relief for those residents. So there seem to be two sets of criteria in terms of how the city responds to things in these highly resourced areas and how they respond to things in the rest of the city.

MT: And that raises the issue of public policy decisions, and how they could help bridge that gap or in some ways exacerbate it.

Yakini: Yes, for sure. I mean, it seems that the elected, appointed and imposed officials running the city of Detroit are still functioning on those sort of trickle-down economics, that if we bring very affluent people to the city, that sort of affluence will trickle down to the rest of the city, as opposed to really building Detroit from the bottom up.

MT: But let’s say somebody makes an argument that when you have more people of means living in the city and paying their taxes, doesn’t that rising tide raise all boats?

Yakini: I would ask they show me some historical examples of that. I would just suggest to them that I don’t see where the historical record plays that out. Certainly we’re not seeing that currently in the city of Detroit; we’re seeing the creation of two distinct narratives. We’re seeing a Detroit, again, which is highly developed, highly resourced, and apparently getting favor in regards that the rest of the city does not get. So, we’re just not seeing this sort of rising tide causing all boats to rise. We’re seeing the exacerbation of class- and race-related differences in Detroit.

MT: Well, how do you go about raising the consciousness of people moving into the city?

Yakini: Well, one of the basic things I recommend people do is that they participate in the monthly sessions that are called “Uprooting Racism, Planting Justice.” And this is an effort that has been going on in Detroit since 2009. On the first Saturday of each month, there’s a public discussion that looks at how racism impacts the food system in particular, but impacts development and our vision of the future of Detroit in general. So, engaging with others who are also trying to understand how race impacts their own behavior is valuable. None of us functions in a vacuum, and even those who are trying to transform ourselves, do that in the context of a collective. So, having others who are also striving to go through that transformation that you can touch bases with is very helpful. That may be a good first step, just engaging in discussions with others who are grappling with these issues and figuring out how to come into the city being a good ally as opposed to creating more stark class and racial divisions.

MT: Even though they may be well-meaning people…

Yakini: Yeah, I think that most of the people moving into the city of Detroit are well-meaning. I don’t think that most people, you know, come into the city of Detroit with the intention of causing some harm to someone else, you know, or trying to disempower Detroit’s African American community. But the way the system of white supremacy works is that if you don’t constantly work in opposition to it, you unconsciously advance it. So, it’s not really a question of intent, but it’s more of a question of one’s knowledge base and using that knowledge base to refine one’s intentions.

MT: Is there anything you’d add to that?

Yakini: I would add that it’s important that people coming into the city spend their money consciously, because it’s possible to just spend money in these highly developed enclaves and not really spread that prosperity through the rest of the city. There are a number of businesses owned by African-Americans in the city of Detroit that are worthy of support by those moving into this community. I’ll start with, of course, D-Town Farm — I have a vested interest in that. We would certainly like people coming into the city of Detroit to visit D-Town Farm and get a greater understanding of the urban agricultural movement and how we’re using that as a lens, so to speak, to create social justice. But also you have places like Baker’s Keyboard Lounge on Livernois and Eight Mile, which is the world’s oldest jazz club. You have the Blue Nile restaurant, which is actually in Ferndale, outside the city limits of Detroit, but nonetheless an important, in this case, African-owned restaurant, which is simply a jewel in this community. You have Goodwell’s Natural Food Market on Willis near Cass that people should be familiar with and should support. And, of course, you have the Museum of African-American History, which is the largest African American museum in the country. So, all of those are the types of places that not only would newcomers benefit from in terms of their vision being expanded but also gives them the opportunity to spread some of the wealth that they may be bringing into Detroit, into communities and to institutions that are greatly in need of it.

MT: Ideally, everyone is enriched whether financially or culturally.

Yakini: Absolutely.