The plan, early on, was to hide the letters in the church. The tight recesses at the ends of the pews or the dusty corner of the room would provide ample cover for a folded slip of paper. Everyone at church, directing their attention to casual conversations and prayer, would be too busy to notice. Only the writer and the recipient would be aware of the letters' existence.

Moving into digital communication would be challenging. Emails left a digital trail. And there was a larger concern with emails — adults could access emails, especially when those adults are parents to an 11-year-old boy. And if they did get access, secrets would be exposed and explanations would be in order.

So the letter writer and his recipient created a complex code in their emails, a safeguard for future conversations and a way to expand upon the letters exchanged within the walls of the church.

But in spite of all these protective measures that Patrick McAlvey went through as a young boy, all in hopes of curing himself of his homosexuality, he did not feel helpless at first.

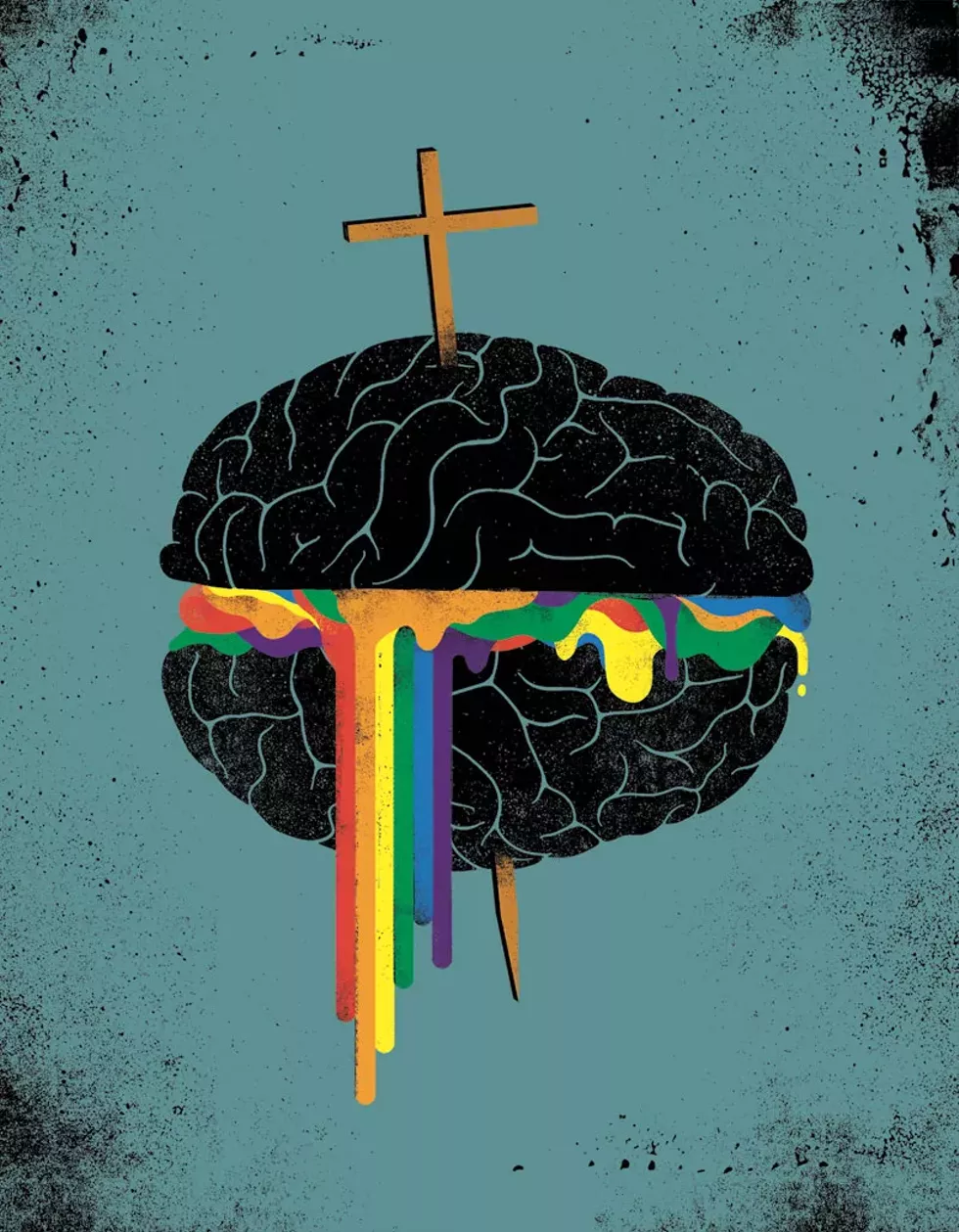

Patrick already knew he was a sinner; he had been having thoughts of "same-sex attraction," and the church community that he was raised in had always made it a point to condemn homosexuality. Same-sex attraction, he was told over and over again, was wrong, sinful, and unnatural.

But he was also told he could be changed. At the same time that the church espoused the evils of homosexuality, it also offered a path for salvation. God could change you. God could cure you. And if God ever needed any assistance, there was always Mike Jones.

Jones was a member of University Reformed Church, the East Lansing church that McAlvey once attended. He was respected and well-liked. But Mike Jones also billed himself as an expert in a practice known as conversion therapy — the pseudoscientific practice that attempts to convert a person's sexual orientation to heterosexual.

Patrick was 11 years old when he first reached out to Jones to fix the thoughts of same-sex attraction that had been flooding his mind. The clandestine system of communication they established — the tucked-away letters in the church, the coded emails — began a therapist-patient relationship that would stretch more than nine years.

Their relationship was centered on converting Patrick by reminding him of the evils of homosexuality, and by reinforcing that, with some counseling, he could rid himself of it.

"The worst part about what he did to me at that young age was to really reinforce and teach me that it is bad to be gay," McAlvey, now 33, says. "That everyone who is gay is addicted to drugs and alcohol and random sex. That none of them are happy. That a lot of them die of AIDS. But he also told me that change was both possible and necessary, and that I could and should change."

Little by little, the letters and emails grew more frequent. Soon, Jones was providing Patrick with resources and books that further emphasized that homosexuality was sinful and demonic. Though their relationship began as one more impersonal and distant because of Patrick's young age, it grew more intimate as Patrick became older and felt even more helpless and defeated in his struggle to change his sexual orientation.

"For nine or 10 years, just changing myself became the focus of my life," Patrick says. "And really as time passed and I didn't change, I learned to hate myself because I felt that there's this thing about me that is bad and that I can change it, other people can change it, and if I can't change it, it must be because I have not tried hard enough or I am not faithful enough to God."

McAlvey left Michigan and Jones behind after he completed high school for a missionary training school in Philadelphia. But he was kicked out in less than a year after he had disclosed that he struggled with what he called same-gender attraction.

Now even more lost and more desperate to "cure" himself, McAlvey returned home and contacted Jones once more to finally fix him. It was when he returned home that he met with Jones more intensively, several times a week for often the entirety of the day, over the course of four months.

"That's when a lot of the weirder stuff happened," he says.

Jones would allegedly implore McAlvey to confront his sexuality with graphic images and probing questioning. He had to describe his penis, his pubic hair, and his sexual fantasies in detail to him. He played a movie that had full-frontal male nudity. One day, Jones told Patrick that they would try something that he called holding therapy, in which Patrick lay in Jones' arms for an hour, locking eyes with him and smelling his body.

"I felt I had no choice but to — he had a lot of power over me," McAlvey remembers. "I felt like I had to do whatever he said because I was so desperate to change and he was the one who knew how to change me."

In 1935, an American mother wrote to Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, asking him to treat her son's homosexuality. In a letter that would later become famous, Freud wrote back:

"I gather from your letter that your son is a homosexual. ... It is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation; it cannot be classified as an illness; we consider it to be a variation of the sexual function, produced by a certain arrest of sexual development. ... By asking me if I can help [your son], you mean, I suppose, if I can abolish homosexuality and make normal heterosexuality take its place. The answer is, in a general way we cannot promise to achieve it."

Though Freud questioned the ethics behind conversion therapy in the letters, his theories on homosexuality were more complex. Both opponents and proponents of conversion therapy would cite Freud as justification for their beliefs well into the 19th century.

After Freud's death in 1939, however, many psychoanalysts diverted from the Freudian view of a normalized homosexuality and instead adopted views based on the work of Sandor Rado, a Hungarian psychoanalyst who believed that homosexuality was unnatural and a consequence of inadequate parenting. This new school believed homosexuality not only to be unnatural, but also mutable.

This group of psychoanalysts published studies that concluded that changing an individual's sexual orientation was possible. The studies provided an intellectual backdrop for the aggressive conversion therapy experiments performed on homosexuals in the period between Freud's death and the Stonewall Riots in 1969. Experiments ranged from electroshock therapy to "aversion therapy" in which LGTBQ people were given vomit-inducing chemicals when they looked at their lovers. Conversion therapy was widely accepted in the medical, academic, and social world. Time magazine even published a 1965 article titled "Homosexuals Can Be Cured" that praised a group therapy session of homosexuals led by psychiatrist Samuel Hadden.

But the Stonewall Riots and the ensuing LGBTQ rights movement in the decades to follow chipped away at the acceptance of conversion therapy. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its manual on mental disorders. A flurry of influential studies into the 21st century dismantled the case for conversion therapy.

In many respects, the gay rights movement that started at Stonewall has been successful in its crusade against conversion therapy. The practice is now universally understood to be pseudoscience and damaging to mental health by health care professionals, gay rights groups, and politicians alike. The APA now states its opposition to conversion therapy more forcefully, saying, "The potential risks of reparative therapy are great." The former United States Surgeon General David Satcher in 2001 issued a statement that "there is no valid scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed." And after the 2015 suicide of Leelah Acorn, a 17-year-old transgender teen who had undergone conversion therapy, the Obama administration spoke out against the practice. "As part of our dedication to protecting America's youth, this administration supports efforts to ban the use of conversion therapy for minors," wrote Valerie Jarrett, a senior adviser to President Barack Obama.

Even in many Christian groups, historically among the strongest supporters of conversion therapy, the tide seemed to be turning. After spending $600,000 on pro-conversion therapy ads in The New York Times, USA Today, and other publications as part of a 1998 campaign that Robert Knight of the Family Research Council referred to as the "Normandy landing in the culture war," Christian support for the practice withered. There was no longer new science to provide the empirical backdrop for the therapy. Just as the APA had done in 2000, other large medical organizations had forcefully come out against conversion therapy, debunking it as pseudoscience that was detrimental to one's mental health.

In the 2000s, high-profile Christian leaders of the movement had also come out themselves or had been exposed as gay. John Paulk, who had been a vocal advocate of conversion therapy on behalf of Exodus International, the now-defunct, influential, pro-conversion therapy organization, was photographed at a gay bar in 2000. Ted Haggard, the former president of the National Association of Evangelicals who unsuccessfully attempted to convert himself, was revealed in 2006 to have hired a male prostitute on numerous occasions.

A surprise announcement from Alan Chambers, the president of Exodus International, seemed to signal the end of the Christian pro-conversion therapy movement. At the organization's 38th annual conference, Chambers, who for years was a leading ex-gay voice in the country, announced that he no longer believed that sexual orientation could be changed.

"I am sorry for the pain and hurt many of you have experienced," Chambers wrote in a letter at the time. "I am sorry that some of you spent years working through the shame and guilt you felt when your attractions didn't change. I am sorry we promoted sexual orientation change efforts and reparative theories about sexual orientation that stigmatized parents." Conversion therapy in the 21st century appeared to be on its last legs.

An inflammatory incident in metro Detroit this year, however, illuminated to the public that conversion therapy was still alive and well in Michigan, and that its advocates had merely changed the way it was marketed in response to mounting pressure. In February, a post by Pastor Jeremy Schossau of Metro City Church in Riverview advertised a $200, six-week workshop targeting 12 to 16-year-old girls who are gay, bisexual, or transgender. The post promised an "Unassumed Identity Workshop" to "help your girl be unashamed of her true sexual identity given to her by God at birth."

The backlash was swift. Less than a week after the post, more than 300 people gathered outside Metro City Church's location in Riverview, holding signs calling for Michigan to become, at the time, the 10th state to ban conversion therapy. The Metro Detroit Political Action Network, the group that organized the protest, called for a formal investigation of the church and for more demonstrations until the workshop ended.

"We think an investigation will unearth that conversion therapy is practiced and hope that the attorney general will issue a permanent injunction against Metro City Church from practicing conversion therapy," MDPAN chairperson Brianna Dee Kingsley told Metro Times after the Feb. 8 protests.

Schossau made the media rounds to vehemently deny that the workshop was conversion therapy. In a February email to Metro Times, Schossau promised to continue the workshops and to hold similar ones in the future. He ended the email saying, "the hypocrisy of the gay community is so incredible because they are not seeking to understand and making totally wrong assumptions."

Schossau also posted a five-minute video to YouTube defending himself, saying in the video, "A lot of people are calling this conversion therapy, and if you think conversion therapy is grabbing somebody, forcing them into some sort of pastor's office and then beating them over the head with the Bible, and condemning them and spitting on them and judging them — that is wrong, we oppose that in every single way."

This May, however, Schossau was honored in Washington, D.C. by the Family Research Council, a self-described "leading voice for the family" whose defamatory practices against the LGBTQ communities have branded it a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center. In 2014, the FRC also testified in opposition to legislation that would ban conversion therapy in Washington D.C., citing "abundant anecdotal ... and scientific evidence" that these therapies work.

And although Schossau has distanced himself from the conversion therapy label, Seth Tooley, an 18-year-old transgender man, said he underwent conversion therapy at Metro City Church when he was younger. Tooley says that he was 13 years old when his mother put him in counseling sessions in the church to treat symptoms of depression. After the pastor who was counseling him had learned that he was transgender, Tooley says that his next session became an exorcism. According to Tooley, Schossau and two of the church elders appeared at his next therapy session and surrounded him holding Bibles. They began to chant, "The demon must leave this girl." Schossau's role in the ordeal was indelible.

Conversion therapy is still alive and well in Michigan — its advocates had merely changed the way it was marketed in response to mounting pressure.

tweet this

"Jeremy was there, they were his backup, his sidekicks," Tooley tells Metro Times. "It was Jeremy who orchestrated it."

That was the last day that Tooley and his mother went to Metro City Church. But although the therapy session prompted them to leave voluntarily, the Tooleys allege that church leaders threatened to call the police on them if they returned.

"I was terrified to sleep in my own bed because I thought that I had a demon inside of me. Now, I can't step foot inside a church now without thinking to myself that everyone thinks I'm bad," Tooley said. "I love God, but I hate church."

There are others, Tooley says, who have gone through similar experiences but won't speak out for fear of retribution.

"I have many friends who have went through conversion therapy in other churches," Tooley says, "but they will not speak out because of their parents, or the church, or because of stigma."

Liam Vella, who says that he underwent conversion therapy at the Inter-City Baptist School in Allen Park, agrees that it is difficult for survivors of conversion therapy to speak publicly about their experience because they feel isolated within their communities.

"Looking back, there were other kids at my school and church who were going through the same things," Vella says. "It's kind of a shameful thing. There are no announcements or support groups for people who had gone through with it."

As a teenager at Inter-City Baptist, a small private Christian school that operates within the church, Vella says that over the course of months he was forced to attend regular therapy sessions with school administrators and church pastors. They shouted at him during therapy, saying he would go to hell if he did not repent and recited Bible verses to him. He had to fill out worksheets designed to condemn homosexuality and convert him. During these sessions, Vella says he was threatened repeatedly with losing the school and church social circle that he had been a part of since he was 2 years old.

"These were esteemed figures that I had known for a long time," Vella says. "As a kid in eleventh grade who's still developing and figuring out who you are, to hear these people you are supposed to trust in bully and threaten you — tell you you're going to be expelled, lose all your friends, sent to a different state — you feel trapped."

As the pastors and school administration grew dissatisfied with Vella's inability to change after months of therapy, they brought him to the principle and issued him an ultimatum: Say whether you believe being gay is abominable, or be expelled from school and excommunicated from the church. Vella answered negatively. That was his last day at Inter-City Baptist.

Michigan has long had a poor track record in upholding protections for the LGBTQ community.

According to FBI data, Michigan had the fourth-most hate crimes in the country in 2016, and has seen a wave of attacks on LGBTQ individuals in recent years. There was Coko Williams, the transgender woman who had her throat slashed and was fatally shot in 2013. Then there was Calvin Lipscomb, another transgender woman, whose body was burned so severely that she could not be identified for 11 days. Then came an incident in which a 28-year-old Michigan woman was beaten unconscious by three men after they recognized her from the television coverage of her same-sex marriage, then a woman in Brighton, who was approached by two men and allegedly told, "Just so you know, we hate fucking dykes and so does our president."

And then there was the young man in Muskegon Heights, who was stripped and beaten because of his sexual orientation, but whose attacker could not be prosecuted under Michigan's hate crime law, known as the Ethnic Intimidation Act, because it leaves gender identification and sexual orientation off its set of protections. D.J. Hilson, the Muskegon County prosecutor, says his office was barred from pursuing a felony charge of ethnic intimidation against the suspect because of Michigan's current hate crime laws.

"I don't get to make the laws, I just get to enforce the laws that are made," Hilson told Grand Rapids' WOOD-TV. "And we're hoping that this will highlight the need to make change in this particular law."

Additionally, Detroit was named the most dangerous city in the nation for gay travelers by Alternative Luxury Travel by Bruvion, a 2012 survey by The Guardian placed Michigan's LGBTQ protections on par with Mississippi, and Michigan law also makes surrogacy for same-sex couples illegal. And although LGBTQ advocates have been energized by the recent election of Dana Nessel, who will serve as Michigan's first gay attorney general, there remains much work to do in order to undo the crippling policies conjured by Michigan's two most powerful government officials.

In 2015, Gov. Rick Snyder signed a law that permits child placement agencies to not provide services that conflict with their religious beliefs, a move that LGBTQ advocacy groups say bars same-sex couples from adoption. The ACLU of Michigan filed a lawsuit challenging religious discrimination against same-sex couples in Michigan's public child welfare system earlier this year. In July, Attorney General Governor Bill Schuette signed an opinion that undercut the Civil Rights Commission's reinterpretation of the Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act to include protections against discrimination for LGBTQ people in housing and employment. As a state senator in 1996, Schuette also cosponsored a law that outlawed gay marriage in Michigan, and as attorney general, he defended the state's gay marriage ban in a drawn-out legal battle that was ultimately struck down in a 2015 landmark U.S. Supreme Court case.

Although LGBTQ advocates have been energized by the recent election of Dana Nessel, Michigan’s first gay attorney general, there remains much work to do.

tweet this

On the snowy February night when nearly 300 protestors had gathered outside Metro City Church to denounce conversion therapy, many had Michigan's complicated history with protecting LGBTQ rights in the back of their minds. A ban on conversion therapy, advocates argued, would be a way for Michigan to reverse course and demonstrate that it cares about protecting its LGBTQ communities.

But signing legislation that banned conversion therapy would also be more than just a show of good faith. In January, the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law published a major study that estimated that nationwide about 20,000 LGTBQ youths currently between the ages of 13 and 17 will undergo conversion therapy from a licensed health care professional before the age of 18 and another 57,000 will undergo the therapy from a spiritual or religious figure. And 700,000 LGBTQ individuals, the study further estimated, have already undergone conversion therapy at some point in their lives — nearly half of whom had underwent it as adolescents.

According to Christy Mallory, the state and local policy director at the Williams Institute and the lead author of the study, laws that ban conversion therapy could protect the many thousands of teenagers who are currently at risk. Since 2012, 14 states, 45 localities, and the District of Columbia have banned conversion therapy for minors.

"Our research shows that laws banning conversion therapy could protect tens of thousands of teens from what medical experts say is a harmful and ineffective practice," Mallory says.

In Michigan's state legislature, however, legislation has seen little progress.

State Representative Adam Zemke (D-Ann Arbor) first introduced legislation to ban gay conversion therapy for minors in 2014. House Bill 5703 would have prohibited mental health professionals from attempting to change the sexual orientation of minors.

The legislation did not pass. Rep. Gail Haines (R-Waterford), chair of the House Health Policy Committee, told the MIRS subscription news service at the time that she believed "creating new laws that intervene in the relationship between parents and a child seems unnecessary," and that her committee had other bills to consider that year.

Zemke tried again to pass legislation in 2016, this time with a republican sponsor on the bill. Again, the bill went nowhere.

After the Metro City Church incident in February, Zemke and Rep. Darrin Camilleri (D-Brownstone Township) once more introduced the bill, now known as House Bill 5550. They also wrote a letter to Attorney General Schuette to investigate Metro City Church as a matter of fraud for violating the Michigan Consumer Protection Act by marketing and selling proven pseudoscience sessions for $200.

But the bill has stalled in the house legislature, and Zemke and Camilleri have yet to hear back from the attorney general. Neither expect to see progress any time soon.

"Republicans don't seem to believe in conversion therapy at all," says Zemke. "They don't want to be seen as being anti-consumer or anti-LGBTQ, but their base views this is as a religious issue. This is a medical issue, not a religious one."

Even if the legislation were to pass, Zemke acknowledges that enforcement would be difficult. It would rely largely on individual reporting to seek out and punish the therapists who perform the therapy, which Zemke says is standard practice for the Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs' licensure revocation. But many of the individuals who perform conversion therapy, especially in spiritual or religious circles, are unlicensed, making it difficult to go after Mike Jones, who was unlicensed, or even Schossau, who previously told MT that he purposefully uses non-licensed therapists for this very reason.

Camilleri believes that the Consumer Protection Act is one way to address the gap.

"What makes it difficult is that there is a perception that this bill alters the separation between church and state," Camilleri says. "What we are really trying to point out is that they are charging residents and selling them a product that does not scientifically work."

For now, Zemke and Camilleri say they must wait until the midterm elections to see if seat changes in the legislature bring in more people who believe that conversion therapy is prevalent and pressing.

"It's a real issue everywhere and it's really a real issue when it gets into children," says Zemke. "Every person who has called my office, every person who I have talked to about this, literally every individual who has gone through this, has talked about the lifetime of trauma. This stuff doesn't work, period."

Today, McAlvey works in human resources at a global technology company in the Netherlands. McAlvey decided to go public with his experience nearly nine years ago in a YouTube video and then through tweeting about Jones to the president of Exodus International. The video and tweets resulted in Exodus International dropping its ties with Jones, citing its opposition to the "holding therapy" that McAlvey endured. Shortly after, McAlvey was approached by East Lansing's CityPulse, where McAlvey worked closely with a young reporter who booked four therapy sessions for $250 with Jones.

In the years since he published the video, McAlvey says he has heard from hundreds of people from not only Michigan, but also all across the country and the globe, who have undergone similar treatment. Their stories range from failed marriages to women to still trying to become straight in adulthood to living a life of celibacy. But each one shares the same scars left by the treatment.

"There's been a lot of sad stories where a lot of people are hurting and are still confused," says McAlvey. "They don't want to lose their family or their community, but they are living in limbo, in some sort of in-between where they might be out in some parts of their life but not in other parts."

Despite speaking out about his experience, McAlvey still carries the lasting emotional and mental damage it caused with him in ways that he says will never be healed. Like McAlvey, Zemke has heard from many survivors of therapy in Michigan since he first introduced legislation in 2014, who are traumatized years after the treatment.

"Young people feel shame, I've seen depression, anxiety, people attempting or commiting suicide," says Zemke. "The effects are just devastating."

"I think a lot of it happens in communities that are a little sequestered away from the mainstream, so it's hard to reach those people or know those people exist," says McAlvey. "There are definitely lives at stake."

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.