Lapointe: Sportscaster Ron Cameron was one of a kind

Around Detroit arenas, he was here, there, and everywhere

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

I first met Ron Cameron on Opening Day of the 1967 baseball season when I worked as a “badge boy” usher at Tiger Stadium.

Unescorted, Cameron sat down in an empty, wooden, green-painted chair in my reserved section in the upper deck on the first-base side of the home-plate backstop. At age 15, I held power and responsibility on the aisle between Sections 22 and 23.

“May I see your ticket?” I asked Cameron.

“I don’t need a ticket,” Cameron explained to me, with a smile. “I’m always here.”

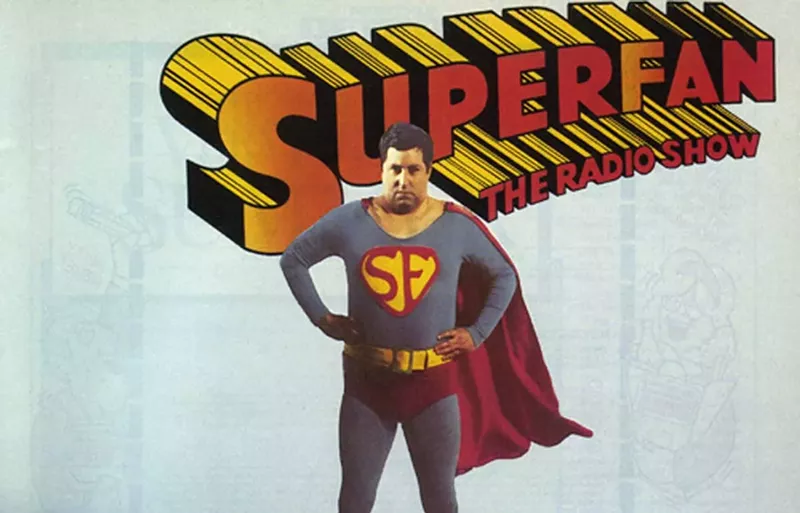

And Cameron remained here — and there, and everywhere — on the Detroit sports scene for decades, a populist fan-journalist who worked in radio, television, and print as an eccentric commentator and singular presence.

Ron always wanted to be in the know, to be in with the “in-crowd,” to be the first to learn and spread the latest news, rumors, and gossip. His old friends called him “Scoop.” And — on a Red Wings radio broadcast late last month — I first heard the sad scoop that Cameron had died at age 79.

They found him in his motel room in Warren. The cause has not yet been announced. No foul play is suspected. Until his death, Ron was “always here,” at Tiger Stadium, Olympia Stadium, Cobo Arena, the Silverdome, Joe Louis Arena, the Palace, Ford Field, Comerica Park, and Little Caesars Arena.

Cameron once told me he shook hands with Tigers legend Ty Cobb in front of Briggs Stadium in 1960. In that Cobb was Detroit’s most famous former athlete at the time and Cameron would eventually become a Detroit sports figure of a certain kind, Ron no doubt must have assumed Ty wanted to meet him.

You want a Ron Cameron anecdote? Here’s one. We were riding westbound in a black 1967 Mercury Cougar on the Edsel Ford freeway late in the 1960s. I was in the front passenger seat. Cameron and my brother were in the back seat.

None of us wore seat belts. Ron and I began to argue about something stupid, no doubt regarding sports, because Cameron never, ever thought of anything but sports. In his diplomatic manner, Ron sucker-punched me in the back of the head. I swung back.

Our driver quickly requested that we cease and desist, in that the vehicle remained in motion at high speed. Like a linesman at a hockey game, my brother broke up the fight.

And I’m one of the people who really liked Ron Cameron. Not everyone did. He came up the hard way. He rarely mentioned any family ties. No one taught him the social graces. He had many rough edges in grooming, eating habits, and debate manners. He lacked subtlety.

But he persisted and drew grudging respect around sports. Another journalist who liked Cameron was Bob Page, who co-hosted a TV talk show with him and tried to balance Cameron’s bleacher-bum perspective with a more polished and professional presentation.

“A very TOUGH life,” Page said of Cameron in a post on social media. “[Ron] never knew his dad, thrown out of the house by his … mother at 15 to fend for himself on the streets of Detroit! He never attended a day of high school. No matter what anyone thought of Ron Cameron, it was amazing what he was still able to accomplish!”

Ron always had big plans of what he would accomplish next. He first wanted to be an umpire, but that didn’t work out. However, he did befriend major-league umpires, driving them to and from their hotels and the airport, a major favor back when their regular pay was skimpy.

Because he was inclined to support authority figures in sports, Cameron constantly defended umpires, referees, and other game officials. In the late 1970s, during a Red Wings game at Olympia, the organist taunted the three officials by playing “Three Blind Mice” after a disputed call.

That was back when arenas were not bombarded with recorded noise before every faceoff. Sitting in the press box, Cameron charged from his chair toward the organist to berate him. The public relations director of the Wings intervened and ejected Cameron.

He pointed toward the organist and explained to Cameron: “I need him. I don’t need you.”

At the ballpark — when I was a teenage usher, before becoming a sports writer — Cameron was the first person I ever knew who owned a boom box radio. It was huge, but it wasn’t for playing mixtapes of rap recordings.

Ron would lug it around on his shoulder in those days long before the internet and cable TV so he could tune in games and sports reports from all over the country. If a fan heckled an umpire, Cameron would turn around and threaten to hit the fan with his big radio.

Quite a metaphor for the guy who later pioneered no-punches-pulled, sports talk radio in Detroit. We ushers who liked Ron would have to explain again to him that the hecklers — even if they were wrong — were paying customers and Ron was not a paying customer.

He had no known life outside of sports except for restaurants he was always opening and closing. Sometimes, he’d broadcast radio shows from restaurants at lunch hour and read his hand-written commercials about “roaches, rats, and bugs” that his exterminator sponsor could kill.

One of the restaurant owners had to gently ask Ron not to read such stuff in a dining room while people were eating. It had not occurred to Cameron that these things should not go together. And he didn’t like being corrected.

“Ron had a temper,” said Greg Innis, the Red Wings statistician and historian who looked out for Cameron and remained a loyal friend. “He’d fly off the handle.”

As with all of Cameron’s friends, Innis cannot recall seeing Cameron outside the milieu of sports, radio, TV, hotel rooms, and restaurants.

He had no known life outside of sports except for restaurants he was always opening and closing.

tweet this

“He didn’t have a personal life,” Innis said. “If Taylor Swift knocked on his door and said ‘I’m lonely, can I spend the night?’ Ron would say ‘I’ve got to go to a Piston game.’”

He preferred to live in motels. He never forgot a favor, or forgave a grudge. Ron stayed close to Denny McLain, the Tigers pitcher who fell into crime and hard times after a short but brilliant career. McLain was one of Cameron’s last radio guests.

Even after his prime on WXYZ (1270-AM) radio and local TV in the years around 1980, Cameron remained ambitious for adventures beyond Detroit and media roles. He dreamed of moving to California or Florida to run a minor-league baseball or hockey team.

But those things somehow never seemed to work out and Cameron always bounced back to Detroit. His last radio gig was on WPON (1460-AM) in Walled Lake, a faint signal where he sold his own commercial time in a barter arrangement that allowed him to continue his hand-to-mouth lifestyle.

Toward the end of his life, there was more than a little pathos to Ron’s circumstances, but he never sought sympathy for himself. I saw him at a Pistons game at the LCA a few years back and asked how he was doing.

“Just had brain surgery!” Cameron said, pointing to a bandage on his head. He smiled as he said it, as if discussing traffic on the way to the game. No doubt, we both thought of follow-up wisecracks, but we bit our tongues, rare for both of us.

On and off the air, he spoke in short bursts of words and his voice chirped high and shrill when he was emotional, which was often. Innis does a warm and wonderful impression; let’s hope it endures. Cameron’s positive relentlessness was something Innis and other friends of Ron will always fondly recall.

“Ron was bound and determined to be successful in the one interest he had in life,” Innis said. “He worked.”

Subscribe to Metro Times newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter