Lapointe: Might this be Mallory McMorrow’s moment?

Michigan state senator may soon seek U.S. Senate seat

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

The bumper stickers and the yard signs practically write themselves: “McMorrow for Tomorrow,” they might say, or maybe even “from Whitehouse to the White House.”

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves regarding Mallory McMorrow, a blunt-speaking (and relatively young) Democratic state senator from Royal Oak who just might be Michigan’s version of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez or maybe even Barack Obama.

Raised in Whitehouse, New Jersey, and educated at Notre Dame, McMorrow is serving her second, four-year term in the state Senate at age 38. She is expected to announce soon her candidacy for Michigan’s U.S. Senate seat being vacated by the Democrat Gary Peters.

In addition, McMorrow just published a book titled Hate Won’t Win: Find Your Power & Leave This Place Better Than We Found It. In a telephone interview late last week, she was asked how Republicans and President Donald Trump have seized control of the national narrative.

“Republicans are really good at story,” McMorrow said. “We’ve got to get better at story-telling and telling an aspirational story of the new American dream that people want to see themselves in.

“We’re letting Republicans define Democrats in ways that are untrue . . . Instead of fixing the issues, Republicans will tell you it is somebody else’s fault to make you angry and fearful of somebody else.”

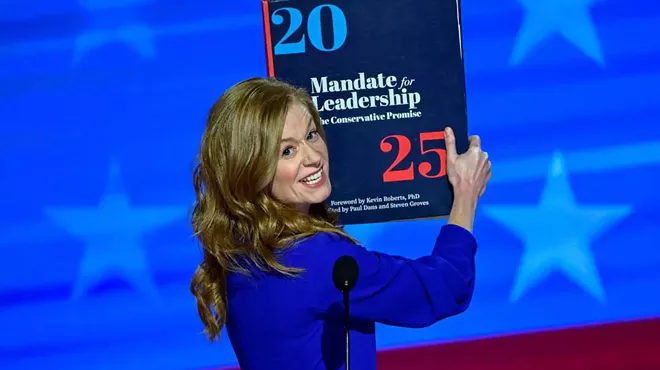

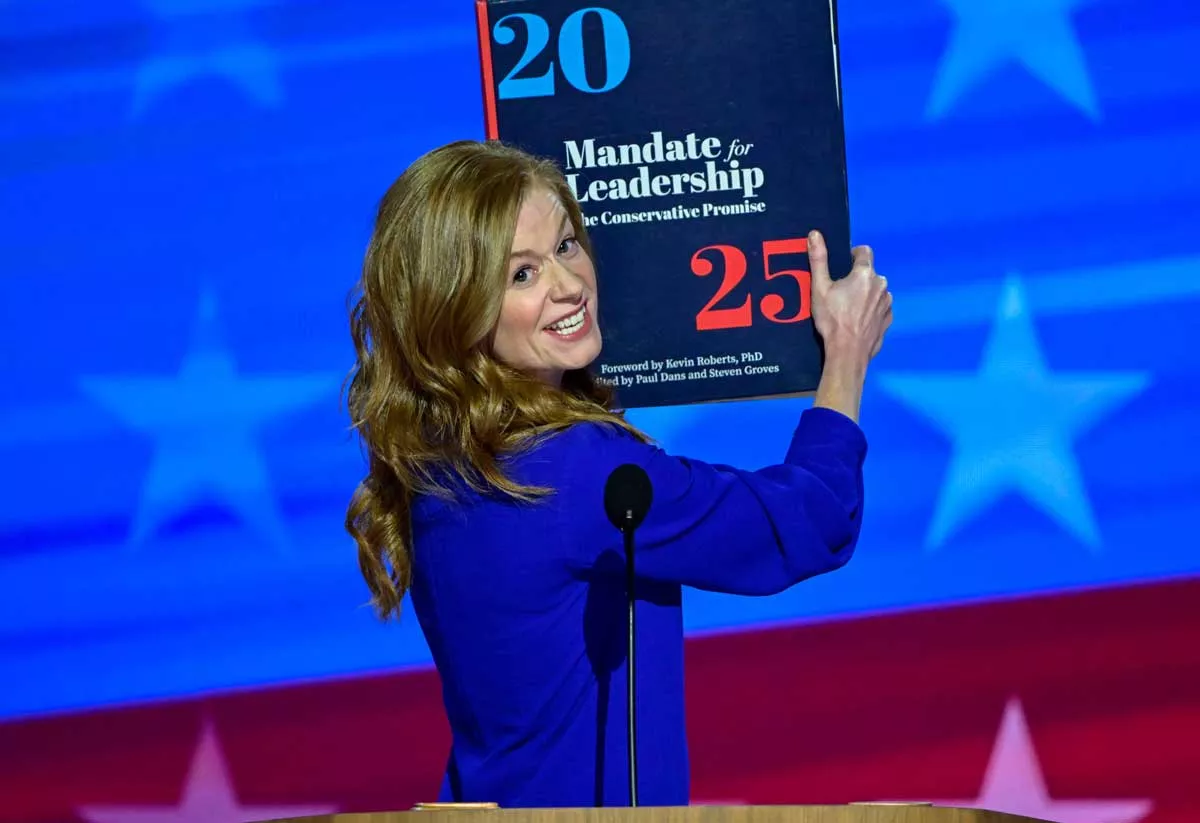

McMorrow’s national profile grew last summer when she addressed the Democratic national convention that nominated Kamala Harris to run against Trump, who prevailed for the second time.

Onto the convention stage McMorrow brought a prop that looked like a large book to represent “Project 2025,” the plan by which the Trump administration is now radically attacking the federal government. McMorrow’s words proved prescient.

“If Donald Trump gets back into the White House, he’s going to fire civil servants, like intelligence officers, engineers, and even federal prosecutors if he decides that they don’t serve his personal agenda,” McMorrow told the convention. “They’re talking about replacing the entire federal government with an army of loyalists who answer only to Donald Trump.”

Two years before, McMorrow’s national breakthrough came after she was insulted by a Republican State Senator, Lana Theis of Brighton, because McMorrow supported LGBTQ rights and the teaching of American racial history in schools.

In campaign fund-raising literature, Theis wrote: “Progressive social media trolls like Senator Mallory McMorrow (D-Snowflake) . . . are outraged they can’t teach, can’t groom and sexualize kindergarteners or that 8-year-olds are responsible for slavery.”

McMorrow responded with a speech in the state Senate that went viral on the internet.

“I am the biggest threat to your hollow, hateful scheme,” McMorrow said, speaking of and to Theis without naming her. “You are targeting marginalized kids. You dehumanize and marginalize me. You say ‘She’s a groomer. She supports pedophilia. She wants children to believe they were responsible for slavery and to feel bad about themselves because they’re white.’”

Instead of conceding the moral high ground to the Pharisees of the religious right, McMorrow stressed her Catholic Christianity. She said her mother sometimes missed Sunday Mass to work, instead, at a soup kitchen. Christianity, McMorrow said, means serving the community.

“So who am I?” she asked in her speech. “I am a straight, white, Christian, married, suburban mom . . . Call me whatever you want. We will not let hate win.”

Asked last week about discussing her religion in public, McMorrow said she used to shy away from it.

“I was very nervous for many years to talk about my religious upbringing,” she said. “My relationship with Catholicism is complicated, like a lot of people’s is. On top of that, I’m married to a Jewish man. But I realized when we don’t talk about it, we leave the vacuum for Republicans to really have a monopoly on religion.”

Referring to Theis’s attack, McMorrow said: “Seeing somebody use Christianity as a weapon to hurt people was not the Christianity I was raised in and I realized I’ve got to talk about it more openly.”

When asked to name her heroes in life, she replied: “Oh, my goodness. I’m an Irish girl. So John F. Kennedy is certainly somebody I look up to who wasn’t afraid to take risks and wasn’t afraid to appeal to a broad swath of people.” Her book offers high praise for the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her persuasive power of story-telling.

For the most part, Hate Won’t Win is an engaging mixture of autobiography, personal self-help guidance, and political participation manual. She writes that too many Democrats are venting now to each other through internet silos instead of organizing grassroots resistance.

As an example, she cites revulsion toward Elon Musk, Trump’s unelected Deputy President, who recently delighted a right-wing rally with a stiff-armed salute.

“When Elon Musk very clearly gave the Nazi salute, I saw people for the next 48 hours spiraling on social media, trying to do social analysis,” she said. “You can be angry, but you can’t shame the shameless. No amount of posting about Elon Musk is going to get him to feel any regret. But you can turn anger that is negative into a positive. What if, instead, you signed up for one canvassing shift?”

Her writing style varies widely in Hate Won’t Win. One sentence on Page 199 runs on for 138 words, beginning with “Every now and then . . .” and ending with “. . . carry out public executions on the front steps of the Capitol.”

In other places, entire sentences and even paragraphs take just one or two words, often as not without a verb, as in “Social media.” and “Proudly.” and “To Feel.” and “To grieve.” and “Not you.” and “Not me.”

Short sentences also ask rhetorical questions like, “So why was everyone so miserable?” Parts are a bit wonky, not uncommon for a political book right before a campaign. One example of that is the chapter “Workbook” at the end, which reads like a syllabus for Political Science 101.

In her more personal memoir voice, McMorrow covers career complexities, including motherhood, and feeling “like a human feedbag” and “a soulless food vessel.” Touches of candor include “I bounced in and out of terrible relationships” and that she is “a high-functioning adult diagnosed with ADHD in college.”

McMorrow makes clear throughout that much of her political consciousness has bloomed from the past decade of Trump, the #MeToo movement, and the devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“COVID-19 unleashed a nightmare,” she writes. “The perfect storm of conspiracy theories, hatred, violence and anger. And it was a much more dangerous sickness than any virus.”

At its best, McMorrow’s writing echoes the passion of her speaking style, much like that of Ocasio-Cortez, the outspoken Democrat from New York in the U.S. House of Representatives. McMorrow describes her reaction to seeing a Trump flag fly at a family home in her neighborhood in 2016. The family included little girls.

“At least one of their parents decided that a man openly bragging about sexual assaults was exactly who they wanted to hold the highest office in the United States of America,” she writes. “And they flew that flag. Proudly . . . And just like that — our country went from electing our first Black president to electing a blatantly misogynistic, racist, serial liar . . .”

“When I travel the country, and I speak to people, they ask me what is going on with those women from Michigan.”

tweet this

Sexual assault appears often in Hate Won’t Win. McMorrow describes one against her in high school, another in college, and the unwanted attention she attracted as a freshman in the Legislature from Peter Lucido, then a fellow state senator, now the Macomb County prosecutor.

“ . . . [M]y body entered fight-or-flight mode desperately seeking escape,” McMorrow writes of encountering Lucido. “Grasping my hand tight enough to indicate he didn’t want me going anywhere, he asked where I was from.”

She answered this as well as a question of who she defeated.

“He pulled back slightly and looked me up and down, still holding both my hand and low back,” McMorrow writes. “‘I can see why,’ Lucido told me with a smirk after I’d felt his eyes assess every inch of my body and score me in his mind like a purebred at a dog show.”

Despite moments like this, McMorrow’s recent rise is part of a decade-long movement of women in Michigan politics, particularly — but not exclusively — on the liberal, progressive, Democratic left. It includes Governor Gretchen Whitmer, U.S. Senator Elissa Slotkin, U.S. Representative Rashida Tlaib, Attorney General Dana Nessel, and Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson.

“There is a lot of power in that so many of us ran together,” she said of the pivotal election of 2018. “I am very proud that Michigan is a standout. When I travel the country, and I speak to people, they ask me what is going on with those women from Michigan.”

Her major legislative achievement so far, McMorrow said, is Michigan’s red flag law, “my first bill signed into law,” that allows fearful friends and relatives to petition a court for the removal of a firearm from someone considered dangerous to themselves or others.

“We know that it is saving lives in a meaningful way,” she said.

One of her top advisors is a Democratic consultant named Lis Smith, who “doesn’t try to change who I am.” They were connected by Ray Wert, McMorrow’s husband, who knew Smith had helped raise the television profile of Pete Buttigieg, the former mayor of South Bend, presidential candidate, and secretary of transportation. Smith booked McMorrow on CNN.

“Lis knew I just needed a chance,” McMorrow wrote, “that once people saw me, I’d become their go-to — a fresh new face in politics who was smart as hell and didn’t put up with anyone’s BS.”

Optimistic supporters of McMorrow may envision another parallel career path for her. Obama went from Illinois state senator in 1997 to U.S. Senate from Illinois in the election of 2004 to President of the United States in the election of 2008.

McMorrow also represents the Upper Midwest. Her hometown, “Whitehouse,” is sometimes spelled “White House.” Might McMorrow take the Obama track? That seems far-fetched. But, 20 years ago, so were notions like “President Barack Obama” and “President Donald Trump.”