Reality is up for grabs, and it's getting filmier by the day. The latest evidence is the exposure of best-selling author James Frey as a fraud, a wimp in warrior's clothing who scammed his publisher, the Oprah Winfrey affirmation machine and the grieving families of some dead former schoolmates. And first among Frey's roster of victims are millions of readers and TV viewers whose faith in their fellow humans was shat upon yet again by a rampant American ethos that places commercial gain over truth, then energetically tries to justify it without acknowledging its clear and present dangers.

And we, many of us, eat it up.

Frey's book, A Million Little Pieces, was put on the market as a true account of the author's life as an addict — one who greedily swallowed, smoked or snorted everything he could lay hands on, and in almost supernatural amounts — and as a badass public enemy, wanted in three states. And all by the age of 23. In the annals of drunk tales and doper diaries, Frey — by his telling — was King Loser, one who, when he hit bottom, began digging deeper with puke-encrusted fingernails.

But he was redeemed! And Frey, the iron-willed iconoclast, said he didn't need no stinking 12 steps, and did it alone.

Written in a glass-jagged stream-of-consciousness style, the book suggested not only that a unique new talent was emerging, but that the writer indeed didn't need no stinking rules, including punctuation.

It was first published — between good, hard, trustworthy covers — in April 2003. Typical of much of its critical reception, the Book of the Month Club called it "an uncommonly genuine account of a life destroyed and saved, and the introduction of a bold new literary voice."

It did well, even for a book with a ready audience for voyeuristic memoirs, and continued to do well after its paperback release last September. Then Oprah Winfrey read it, damn near had a heart attack and, despite its icky language and sex stuff, made it the featured choice in her frighteningly powerful book club for people who'll turn never-read classics into million-sellers just because Oprah says so.

In one move, Frey was a made guy, rolling in his painfully won pelf, living large, getting T-shirts printed, making the rounds of the talk shows, entertaining important interview requests and proving that you too, no matter how low you've sunk, can conquer any conqueror if you "hold on." (Frey fans have even had the prosaic little slogan tattooed into their hides as an indelible reminder.)

But Frey is a poseur and a punk.

While he does seem to have been familiar with drink and drugs (although all of those rehab partners who could support the details seem to have tragically died, forever silent), a cop who knew him back in the day likened his criminal career to "Biffy and Buffy saying, 'I think we should steal a stop sign.'"

The cop was found and interviewed by The Smoking Gun, a Web site that has long specialized in celebrity mug shots, arrest reports, crime scene photos and other ephemera that poke ragged holes through the aura that surrounds the rich, the famous and criminal overachievers.

But this time, for the first time on such a scale, the three-man staff of TSG didn't stop there. In a six-week investigation, The Smoking Gun traced Jim Frey back to his childhood home of St. Joseph, Mich., and followed the increasingly unreliable roadmap laid out in A Million Little Pieces until able to demonstrate — in most cases, conclusively — that Frey's breathtaking story was "a million little lies."

Those associated with the book and its tasty commercial success have been scrambling for the past few weeks to give the revelations all kinds of spin. After initially swearing up and down that the book is nonfiction (and so, presumably, not fiction in the main), Big Jim — that's how he's referred to on his recently suspended Web site — allows that there was some embellishment to serve his larger point. The means, he seems to say, justify the end. His publisher and Oprah stood and stand by him, loath to eat at a barbecue whose main dish is their cash cow.

But the startling thing is that readers, who paid for and consumed Frey's deceptions as truths, so often accepted it by saying that no matter how fraudulent, his story inspires. In much the same way, those consumers who've made "reality TV" an ever more revolting and lucrative franchise willingly forget McLuhan's dictum that "the medium is the message," that a camera by its presence alone kneads and changes what happens in front of it.

Big Jim Frey certainly isn't the first literary figure whose art is that of the con (they go back centuries), but he may be the first of them to include readers among his apologists. In 1972 Clifford Irving collected some $750,000 from publishers who couldn't wait to get a piece of the action when he fraudulently said he'd written a scathingly frank autobiography of the eremitic billionaire Howard Hughes. But he had the bad sense to try to pull it off while Hughes was still alive and lucid enough to call it horseshit. The publisher pulled out. Then Irving went to prison. A decade later, the German magazine Stern paid nearly four million bucks for, and started publishing, the diaries of Adolph Hitler, soon found out as pure fraud. The forger, Konrad Kujau, and an associate both did time.

Will the tables turn on Lyin' Jimmy Frey? Will he be brought low — factually, not fictively — by his deceptions? Apparently not. This week, A Million Little Pieces is No. 1 on The New York Times list of nonfiction bestsellers in paperback.

We continue to listen to Frey preach redemption, even those whose very real pain has been appropriated by a preacher who didn't have enough of his own.

Frey didn't merely embellish his "memoir" for literary effect, he stole pieces of it from others and made up most of the rest. He could have been in the cast of Survivor, but he's never been dropped off on a beach, with camera rolling or otherwise.

Briefly excerpted and described elsewhere, The Smoking Gun's "A Million Little Lies: Exposing James Frey's Fiction Addiction" is nearly 14,000 words long. For those of Frey's home-staters who haven't or can't read it online, TSG agreed to let us freely draw from the piece.

The full story is worth seeking out and spending some energy on, as are the supporting documents posted at thesmokinggun.com. In a time of fictional WMDs, elastic ethics policies, warped on-air reality and widespread uncertainty in untelevised life, this piece has something rare going for it. It's real. —Ric Bohy, Editor

As TSG was about to release its story, Frey posted an e-mailed interview request from its investigators on his own Web site. TSG regarded this as "a pre-emptive strike," because Frey called the request the "latest attempt to discredit me. ... So let the haters hate, let the doubters doubt, I stand by my book, and my life, and I won't dignify this bullshit with any sort of further response." Posting the letter was, Frey wrote, "an effort to be consistent with my policy of openness and transparency." TSG found that strange since he'd refused to offer any of the documents that he claimed could prove his tales and were in his possession. Around the time Frey's book was released, he had told TSG, he also had his criminal records expunged:

The author told us that he had the court records purged in a bid to "erect walls around myself." Referring to our inquiries about his past criminal career, Frey noted, "I wanted to put up walls as much as I possibly could, frankly, to avoid situations like this." The walls, he added, served to "keep people away from me and to keep people away from my private business." So much for the openness and transparency.

So why would a man who spends 430 pages chronicling every grimy and repulsive detail of his formerly debased life (and then goes on to talk about it nonstop for 2-1/2 years in interviews with everybody from bloggers to Oprah herself) need to wall off the details of a decade-old arrest? When you spend paragraphs describing the viscosity of your own vomit, your sexual failings and the nightmare of shitting blood daily, who knew bashfulness was still possible, especially from a guy who wears the tattooed acronym FTBSITTTD (Fuck The Bullshit It's Time To Throw Down).

TSG realized that it would also be difficult to prove — or disprove — any of Frey's outlandish claims about both his life as a teenaged addict and drunk, and the vividly gruesome details of his time in rehab, because those who could provide firsthand knowledge were also unavailable:

While the book is brimming with improbable characters — like the colorful mafioso Leonard and the tragic crack whore Lilly, with whom Frey takes up in [the highly regarded Minnesota rehab center] Hazelden — and equally implausible scenes, we chose to focus on the crime and justice aspect of A Million Little Pieces. Which wasn't much of a decision since almost every character in Frey's book that could address the remaining topics has either committed suicide, been murdered, died of AIDS, been sentenced to life in prison, gone missing, landed in an institution for the criminally insane or fell off a fishing boat never to be seen again.

While we do not doubt Frey spent time in rehab, there really isn't anyone left (besides the author himself) to vouch for many of the book's outlandish stories.

In focusing on the criminal past of the self-limned badass and fugitive, TSG discovered that Frey's "nonfiction" recollections both of big-time juvenile delinquency and raging crimes against society were epic tales that blossomed — with the application of much manure — from puny seeds. In tracing back one arrest that was essential to establishing the author's persona as a relentlessly self-destructive outsider, TSG found that the facts were almost comically mundane:

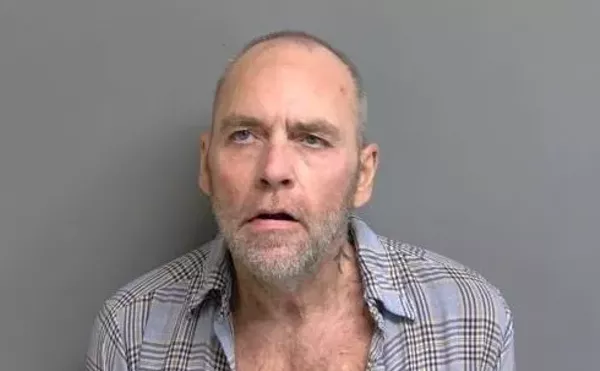

Though he would later write of setting a .36 county record, Frey's blood alcohol level was actually recorded in successive tests at .21 and .20 (about twice the legal limit). As for his claim to have spent a week in jail after the arrest, the report debunks that assertion. After Frey's parents were called, he was allowed to quickly bond out, since the county jail "did not want him in their facility." Because Frey had the chicken pox (which is apparent in his mug shot) and the sheriff did not want him anywhere near other arrestees. Two weeks later, court records show, he pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of reckless driving and was fined $305. No jail, no framed certificate for setting the Berrien County Blood Alcohol Content record.

[When we asked Frey why he didn't move to expunge the records from this DUI arrest, as he did with the subsequent Ohio case, he said, "'Cause I didn't think it was that big a deal. It's not as big a deal as it is in the book."]

Even Frey's timeline for events in the book — and purportedly in his life — proved his story bogus, TSG found:

His habits were underwritten by a monthly allowance from his wealthy and unwitting folks (dad was a top executive). He supplemented his income by selling dope, which brought him to the attention of the local cops and the FBI, who jointly probed his narcotics operation, Frey claims in the book. Amazingly, though he was reportedly a vomiting drunken addict bleeding from various orifices, Frey was able to graduate from Denison [a small liberal arts college in Granville, Ohio] on time in 1992 (talk about managing your addiction!). Maybe it was support from fellow brothers at the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity that helped the Michigan high school outcast persevere. Makes you wonder if Frey had shot heroin, perhaps he would have also snagged a master's.

During these drug-addled Denison days, Frey wrote, "Lying became part of my life. I lied if I needed to lie to get something or get out of something."

While Frey claims to have been arrested several times during college, TSG found evidence of only one bust — and it's the single crime for which he offers any significant details in A Million Little Pieces. Though Frey provides no dates, the incident occurred in October 1992, about five months after his Denison graduation.

Frey wrote that, before driving to an Ohio bar to win back a newly lost love, "I drank as much as I could and smoked as much crack as I could and when I was good and loaded, I decided to go find her and try to talk to her again." He memorializes the encounter this way: "As I was driving up, I saw her standing out front with a few of her friends. I was staring at her and not paying attention to the road and I drove up onto a sidewalk and hit a Cop who was standing there. I didn't hit him hard because I was only going about five miles an hour, but I hit him. The Cop called for backup and I sat in the car and stared at her and waited. The backup came and they approached the car and asked me to get out and I said you want me out, then get me out, you fucking Pigs. They opened the door, I started swinging, and they beat my ass with billy clubs and arrested me. As they hauled me away kicking and screaming, I tried to get the crowd to attack them and free me, which didn't happen." This is what TSG reported, backed up with documents and interviews with the police who handled the arrest:

There was no patrolman struck with a car.

There was no urgent call for backup.

There was no rebuffed request to exit the car.

There was no "You want me out, then get me out."

There was no "fucking Pigs" taunt.

There were no swings at cops.

There was no billy club beatdown.

There was no kicking and screaming.

There was no mayhem.

There was no attempted riot inciting.

There were no 30 witnesses.

There was no .29 blood alcohol test.

There was no crack.

There was no Assault with a Deadly Weapon, Assaulting an Officer of the Law, Felony DUI, Disturbing the Peace, Resisting Arrest, Driving Without Insurance, Attempted Incitement of a Riot, Possession of a Narcotic with Intent to Distribute or Felony Mayhem.

And though he would later vividly write about being consumed by an internal rage that he named like a pet, Frey was somehow able to keep "the Fury" in check on that drunken October night in Granville. As Patrolman [Charles] Maneely reported, he "was polite and cooperative at all times." Frey's arrest was as mundane as they get, as vanilla as the arrestee himself, a neatly dressed frat boy five months out of school and plastered on cheap beer.

Among the police involved in the arrest and booking, TSG interviewed the cop who was allegedly struck by Frey's car:

TSG asked the sergeant if he had ever been hit by an automobile during his 17 years on the force. "No," he said. Would that necessarily have been something he would recall? "I think I'd remember that, yup," he answered, laughing. "There are certain things in your career that stand out to you, like the first time you did an arrest. ..."

"Or the first time you've been hit by a car," [Police Chief Steve] Cartnal interjected.

As for Frey's claims of being the main target of a joint narcotics investigation by local cops and the FBI, TSG found one of those who had headed the operation, former Granville Police Sergeant David Baer. After reviewing records of the intense probe described by Frey, Baer offered his own version:

Calling Frey's account of the drug probe (and his supposed chief role in it) "bullshit," Baer told TSG that Granville police were simply trying to make "nickel bag drug cases." While he wished the case had an exotic, South American angle to it — as Frey tried to make it seem in A Million Little Pieces — Baer said the probe was small potatoes. "We were trying to buy baggies of pot."

The university, Baer said, was not filled with roughnecks and drug toughs. A Denison gang would be "wearing khakis and blue sport blazers. We're not talking Detroit here," he added. "It's like Biffy and Buffy saying, 'I think we should steal a stop sign.'"

On a final note, Baer denied being the overweight Asshole Cop who purportedly threw his coffee at Frey after the wiseass frat boy bolted police headquarters following an interview session that never actually took place. "I was skinny then and didn't drink coffee," he claimed.

Frey the memoirist is a self-effacing but durable hero, a man among men, who made it through stomach-flipping pain and inhuman travail by sheer will, something totally counter to the tenets of Alcoholics Anonymous and similarly structured recovery programs. Of this, TSG wrote:

Frey rejected the 12-step approach and considers addiction a weakness, not a disease (cancer and Parkinson's are diseases, he points out). Frey's reported post-Hazelden recovery was unorthodox, hinging on his ability to continually surmount temptation, thanks to a superhuman will that helped him avoid using at the same time he was purposely placing himself in situations where alcohol and drugs were prevalent. For those struggling with substance abuse, Frey is a shiny, relapse-free success story, a man who beat formidable odds with steely resolve.

For desperate people, there appears to be magic in his approach, though it really boils down to a familiar refrain: Just say 'No.' But since that phrase has long been tainted, Frey has opted for an even pithier maxim: "Hold on." "Whenever you want to go do something you know you shouldn't do, just hold on, and sooner or later you'll feel better," Frey told Sandie [an Oprah viewer who was inspired to check into rehab, where Frey visited her for an on-camera pep talk].

Some of the author's acolytes even get "Hold on" tattooed on themselves. Others prefer to go the T-shirt route, lending Frey's slogan the kind of spiritual heft that can only be found when it's scrawled on a Fruit of the Loom product.

But special scorn was reserved for the section where TSG described the facts behind a fatal train accident that killed two Michigan high school students and injured another. Frey presented his version as validation of his standing as a self-destructive loser who hurt or killed everyone he touched. TSG found that Frey had made himself into a pivotal character in a real tragedy that he had nothing to do with, absconding with and taking as his own the very real pain of the dead students' survivors:

While Frey's fabrications and embellishments of his criminal "career" and jail time are patently dishonest, the section of A Million Little Pieces that deals with a tragedy that took place while he was a high school student is downright creepy and detestable.

On Nov. 15, 1986, at 9:17 p.m., a northbound C&O locomotive pulling a caboose and headed for nearby Benton Harbor slammed broadside into a 1976 Oldsmobile Toronado at the Maiden Lane railroad crossing in Michigan's St. Joseph Township.

The two-door car was driven by 17-year-old Dean Sperlik. Sharing the front seat with him were Jane Hall and Melissa Sanders, both also 17. Hall and Sanders were best friends and classmates at St. Joseph High School. Sperlik, who had moved from St. Joseph to Grand Rapids only months earlier, had previously attended the school with the girls.

According to a St. Joseph Township Police Department report, on the night of the accident, Sperlik hosted a party at a residence where he was house sitting. About a dozen teenage partygoers played pingpong and some, including Sperlik, were seen drinking. Sometime after 8:30 p.m., Sperlik, Hall and Sanders left the party in the boy's auto. Witnesses differed on whether the trio was going to another party or planned to return after purchasing wine coolers.

Less than an hour later, Hall and Sanders were dead, and Sperlik was seriously injured. Despite flashing railroad warning signals, Sperlik, driving at about 50 mph, tried to beat the train through an intersection. Instead, the Olds was hit flush on its right side, where Sanders was seated next to the door. A subsequent investigation determined the car was dragged 626 feet down the tracks.

Sanders, a member of her school's varsity tennis, volleyball, and softball teams, died at the scene from massive head and internal injuries. An autopsy determined that she had no trace of alcohol in her system. Hall, a varsity tennis player and a member of the French club, died of multiple fractures and internal injuries. While seriously injured, Sperlik survived the crash and subsequently pleaded no contest to a negligent homicide charge. He was sentenced to six months in jail and two years probation.

Referring to one of the dead girls as "Michelle," Frey gave this account of the fatal night, as recounted by TSG:

Halfway through eighth grade, Michelle got asked out on a date by a high school boy, Frey writes. Knowing that her parents would not let her go, Michelle told them she was actually heading to the movies with Frey, her beard for the night. "I had never done anything to them and I had always been pleasant and polite in their presence, so they agreed and they drove us to the Theater." Frey adds that he went inside and watched the movie, pint of whiskey in hand, while Michelle got picked up there by her high school suitor (the couple, he said, then went and parked somewhere and drank beer). But as Michelle and the high school boy, a "football Hero," were driving back to the theater — presumably so that Michelle's parents could pick her up — he tried to beat a train across some tracks. "His car got hit and Michelle was killed ... She was my only friend ... She got hit by a fucking Train and killed."

And later:

After learning of the accident the following day, "I got blamed by her Parents and by her friends and by everyone else in that fucking hellhole," Frey claims. "If she hadn't lied and if I hadn't helped her, it would not have happened. If we hadn't gone to the Theater, she would not have gone on that date." Sure, a couple of mangled girls landed in a hospital morgue, but that's narrative gold in the hands of James Frey.

When interviewed by TSG, Marianne Sanders, mother of the real-life "Michelle," said she had read Frey's account, which was completely at odds with the facts of her daughter's death. "When I read that I figured he was taking license ... he's a writer, you know, they don't tell everything that's factual and true," she said. "I just figured he embroidered a few things. ... I mean I'm sure not every single thing he said in there is gonna be true, do you think?"

Send comments to [email protected] or call