Justin Pope was shot and killed in Iraq in 2009 — his family is still trying to figure out who pulled the trigger

Far from home

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Page 2 of 3

Jason Hillestad, Pope's roommate and DynCorp employee, said Pope pointed the pistol at Palmer's head and began egging on his best friend to grab the Glock from his hands.

While roughhousing between Pope and Palmer was common, according to Hillestad, he never witnessed the pair goof off with a weapon in hand. (Palmer would tell federal agents the pair would "fool around" with a gun once a month.)

But the horseplay wasn't included in other witnesses' version of events. Mark Tanner, a DynCorp contractor, said he was looking at Pope at the time of the shot, just before midnight. According to the State Department report, Tanner — who had drank a half-dozen cocktails that night — said he was in and out of the room all night, but didn't see "any horseplay or gunplay between Pope and Palmer."

So did Pope have the gun? Or did Palmer? Again, the files are unclear on that point, and multiple witnesses say they couldn't discern either way.

According to Palmer, he had the upper hand, and Pope shouted at him to "pull the trigger" — though "none of the other people in the room" can corroborate that point, according to Goodman, one of the family's attorneys.

But Palmer says after his friend uttered that sentence, he fired one shot.

Immediately after, witnesses say Palmer left the room, went into the street, and began to repeatedly yell, "I shot Pope."

Michael Boffo, who at the time was the project manager for DynCorp International's protective services unit in Iraq, responded by telling Palmer to "stop saying that." Boffo also told federal agents that Palmer, who was engaged to his daughter, also said, "My best friend's dead" and "I shot my best friend."

Within an hour of the shooting, a helicopter arrived to transport Pope to the hospital. Apparently, Boffo didn't see the use. According to one employee's account, Boffo simply stated: "If there's no pulse, then why are we going to medevac him? I'm just being realistic."

That remark stings Patricia Salser to this day.

"The thing about Boffo that is heart-wrenching for me is that he came to Michigan to meet me and my husband with his wife," she says. "I met him for a lunch at a restaurant — and I had my suspicions already — but to believe that that man who I sat at a table with literally was letting my son just lie there and he didn't even want someone to give him help. He was just going to let him lie there like an animal on the side of the road to die. That's the kind of man that we are talking about."

Pope was pronounced dead at 3:52 a.m. March 5.

Claims of a cover-up

What happened next is, not surprisingly, a matter of conflict.

Pope's family alleges that top representatives at the base ordered employees present at Pope's shooting to go into a room and "not come out until they had agreed upon a story as to how it had happened so they could conceal the truth."

Jeffrey Black was not a witness to the shooting but was on-site for the emergency 4 a.m. meeting, according to the State Department file, and said in a deposition that "every single person in that house, they put them all in the same room to get their stories straight." On ordering such a move amid a criminal investigation, Black, who is a current state trooper in Pennsylvania, put it bluntly: "That's 101; don't do that."

But, as MT previously reported in a 2012 story on this case, a man present in the room (who only spoke on the condition of anonymity and who is also named a defendant in the Pope family's lawsuit) denied that employees were ordered to coordinate their stories.

One witness told investigators he saw Boffo "enter a conference room and instruct the team to not mention alcohol use." Paul Sovitsky, a DynCorp employee, said it was readily apparent the "wild partying type of atmosphere" was being covered up.

"Management didn't want that out," he said in a deposition. "That policy by DynCorp was a joke. I mean, it was completely — prior to that time, it was kind of like a wink and a nod. And by that time, the State Department, if I remember correctly, had already come down and said no drinking. And so they didn't want that connected."

'Tone it down. Don't say that.'

Whatever the directives that night and what was or wasn't said, the file makes clear that drinking was a commonality on the base.

Multiple interviews and videos taken with employees at the DynCorp compound (that have since been entered into court records) illustrate a pervasive and common binge-drinking atmosphere. One employee, when deposed, compared the environment to Animal House. Another says it was common for employees to bring a "case of beers" out to a fire pit each night.

Black says management facilitated the party atmosphere.

"In Erbil, it was common knowledge," he said in a deposition. "You could not have lived on that compound and not known the type of partying that was going on or being tolerated and allowed to happen."

Noah Flemming, who says he considered Pope a close friend, offered his view of the incident in a sworn statement that alluded to the widespread drinking on the base, suggesting there was concern that the company's relaxed policy on boozing would be discovered as a result of Pope's death.

Flemming told federal agents that prior to the shooting, Palmer "started trying to wrestle the pistol away from Justin" before the round went off. Then, Flemming said, his first instinct was "to clean up the beer."

Two employees told federal agents that the room was "sanitized of alcohol." The employees also say Boffo, a former Marine, was spotted removing items from the room. Boffo, who is no longer with DynCorp, supervised a group of 151 people, court records show.

Employees were "running around" outside of Pope's room "putting alcohol in the trash," according to one employee. "A large quantity" of empty and full Corona bottles were recovered in garbage bags, according to the State Department's notes.

And Boffo wasn't done directing the alleged cover-up, according to one employee's recollection. He called another meeting March 5 and when one employee asked "what to say about being drunk the night of the 4th," Boffo's alleged response was this: "Tone it down. Don't say that."

That perception of Boffo's edict to erase alcohol from the conversation was backed up by Resurrection Demacablin, another DynCorp worker, who said he overheard a conversation later that night between Boffo and Derrick Agustin, another DynCorp employee, about drinking on the compound. According to the State Department file, Agustin said of the night Pope died: "We were all pretty blitzed." Boffo responded by saying, "It is comments like that that don't need to be said."

Whatever DynCorp's feelings were toward imbibing on the compound, the State Department report suggests it was of high concern.

Pope and Palmer, for example, both signed U.S. State Department forms acknowledging firearms use while serving as contractors at the U.S. Embassy in Iraq. The form includes this line: "I will not consume alcohol or controlled substances before or during handling of any weapon as outlined in the Mission Firearms Policy."

The policy, records show, was to apply to any "direct-hire or contractor."

Under a section of the policy titled "Restriction on the Use of Alcohol and Drugs," it states:

"Employees will not consume any alcoholic beverages or be under the influence of alcohol or drugs while armed. Employees will not consume alcohol six hours prior to carrying firearms. An employee who is caught breaking this policy will be relieved of their duties and denied future access to the Embassy compound."

Also, disciplinary action may be taken in the event an employee was found in "possession of a firearm while under the influence of alcohol or drugs," the policy says. A possible resolution: "removal from the post" at the Embassy.

Feds remove 11 DynCorp employees

Nothing happened to DynCorp's lucrative $1.2 billion contract with the State Department after Pope's death, but the compound wasn't left off the hook completely.

In a performance evaluation of the contract in July 2010, a State Department employee wrote, "Significant concerns also arose regarding DynCorp's oversight of its own personnel in the field."

Those concerns were partly attributed to the base in Erbil.

"In northern Iraq," the evaluation continues, "lack of management oversight resulted in violations of the standards of conduct, which forced the Government to direct the removal of 11 personnel, including the DynCorp project manager [Boffo], from the contract."

By the evaluator's account, DynCorp failed in its duties, and it was recommended to end the company's contract. That didn't happen, of course, but according to Katie Kalahar, one of the Pope family's attorneys, DynCorp did lose out on an additional lucrative contract because of the incident.

"They were nixed," she says, adding that testimony will be later presented that supports the assertion.

A shifting account

In the days that followed Pope's death, stories circulated the DynCorp compound with all the drama and veracity of a high school cafeteria game of telephone. Predictably, they were not all consistent, but these had the important difference of coming from people in authority. Specifically, there was a rumor that Pope had killed himself.

Around March 13, according to the State Department's memo, DynCorp employee Jack Jordan had a conversation with a co-worker who made some "peculiar" remarks about Pope's death. Jordan asked the employee, "Are you under the impression that Justin Pope shot himself?"

The employee responded, "Based on the reports I've read, yes."

When Jordan spoke to a separate employee, Austin Stoffel, a memo included in the file continues, he was told DynCorp was beginning to investigate the incident "and it could be a suicide."

Jordan was surprised.

"Jordan stated that Palmer knows what happened that night," the memo says.

Stoffel replied: "Palmer drank two bottles of wine and a lot of beers and probably didn't remember much."

The apparent "suicide" theory appears elsewhere: In an email sent March 7, 2009 — two days after Pope died — by DynCorp program manager Pat Dobson to Boffo, Dobson wrote an insurance company seemed to be "fishing for a suicide verdict."

The truth, Dobson wrote, is "Justin got a case of the stupids and paid for it with his life." It's unclear what Dobson meant by his statement, or if he was suggesting Pope accidentally shot himself.

Nevertheless, Boffo didn't address the remark in response but would later say in a sworn deposition that he understood within 24 hours of Pope's death that he knew it wasn't self-inflicted.

The inconsistencies made their way to Michigan, where DynCorp conveyed a number of jumbled storylines to the family in the hours following the incident, as MT previously reported.

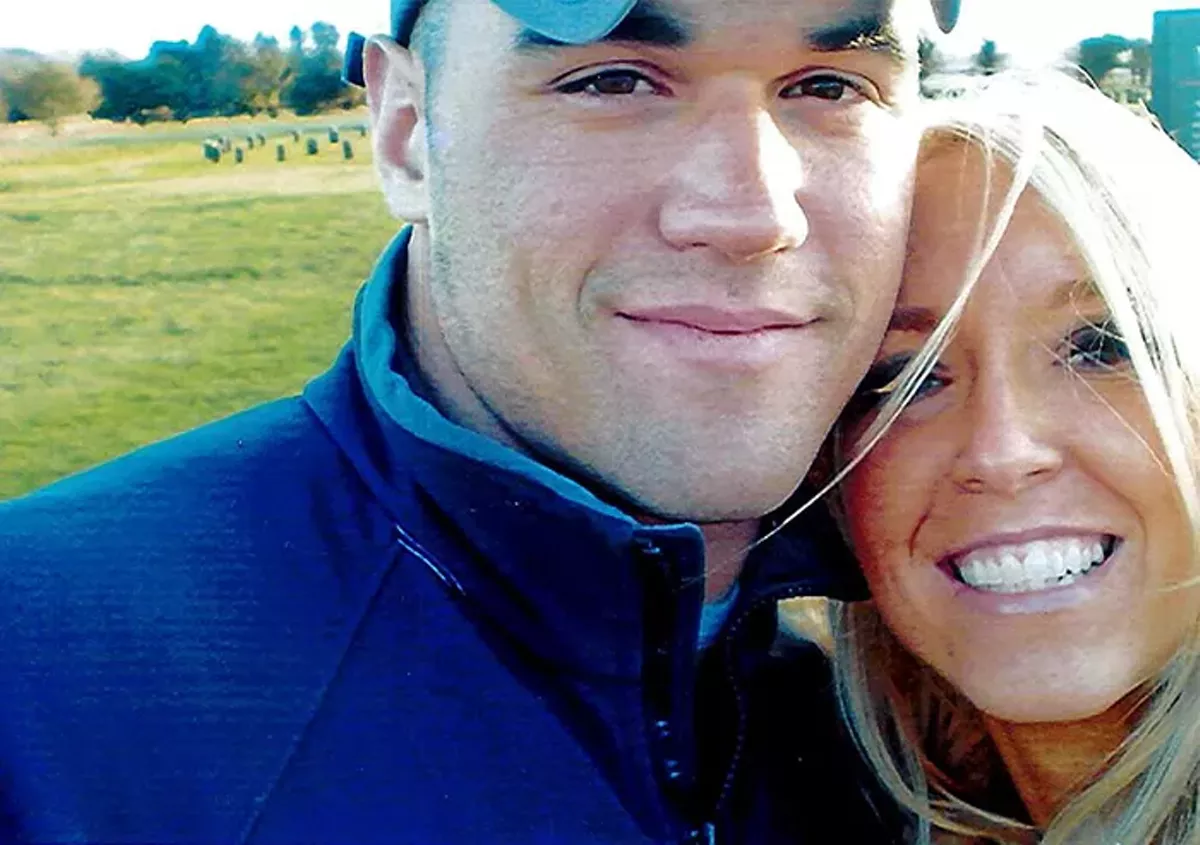

Pope's wife, Ashley, received three calls within a span of several hours following the shooting from Dobson, each offering additional news. The first? Justin was in a serious "accident." Next, Justin was shot in the neck and was transferred to a hospital. Lastly, Justin was dead.

Soon after, Boffo's wife and his daughter (Palmer's fiance) arrived at the Popes' home in Commerce Township to visit Ashley. Ashley was traumatized to the point she had an emotional breakdown.

Michael Kehoe, DynCorp deputy project manager, then arrived. He initially told Ashley that Justin died alone in his room. He also asked another family member if Justin was depressed.

Immediately, the family doubted the implications that Pope either committed suicide or that there was an accident while Pope cleaned his gun.

Pope's brother, Kevin, told investigators he didn't believe the account because it didn't "sound like Justin." The family also said Justin had the utmost concern about gun safety.

"We all knew he was an expert with weapons, as many of those guys were," Bill Salser told MT. "He even taught my wife how to shoot. He taught me all about the safety of it and how guns aren't dangerous but it's the people who don't know what they're doing with the gun. There was no question about — I didn't think that happened."

He continues, "Your mind, when someone dies, you don't know everything that happened but you start to think about all the things you know about that person. We knew that he was a happy person and loved coming home. Everyone answered no [when the initial account was offered], and that says it all."

Kehoe denies telling the family that Pope was alone when he died, court records show. He said in a deposition last year that he conveyed Pope's death "appeared to be self-inflicted" and that alcohol "appeared" to be involved.