The first time Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana, Yusef Salaam, Antron McCray and Korey Wise were in front of the camera for an important reason; it was the April 1989 video confessions they gave to police admitting to having raped and nearly killed a female jogger in New York City's Central Park.

The Central Park Five — a new film examining the case in which they were all convicted, all served their full prison terms, and all had their convictions overturned after the real rapist confessed 13 years later — is one hell of a sequel.

"We hope that this film starts a conversation about lessons learned from this case. It's not an isolated incident, about false confessions and why they happen and how they happen," says Sarah Burns, who co-produced the film with her father, filmmaker Ken Burns, and David McMahon, who co-produced The War with him. "It's about the underlying racism that played such a huge role in this case that led so many people to believe that these kids committed these crimes."

The Central Park Five case was a huge story in 1989. It was at the height of the crack epidemic, and crime rates in New York were at their highest ever. Citizens were screaming for police to crack down on crime. They got what they asked for in a great miscarriage of justice.

The Central Park Five, aged 14 to 16, came into being April 19. They were among a loosely knit group of about 30 teenagers, many of whom didn't even know each other, who wandered through the park harassing bicyclists one evening. One member of the larger group beat up a jogger badly enough that he was hospitalized. After receiving complaints about the harassing crowd, police grabbed several of the boys and took them to the station to wait for their parents to come get them.

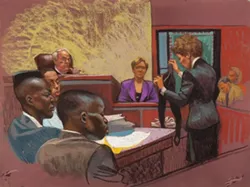

A few hours later, two men found a woman raped and nearly dead in the park. When the call came in, police were sure they already had their perpetrators in custody. The boys were interrogated for 14 to 30 hours — sometimes with their parents present as required by law for juveniles, sometimes not. Many of the things you see in movies and television cop shows seem to have followed.

Detectives told some that the guys in other rooms were ratting on them, that they better hurry up and cooperate before it was too late. Some were told if they gave a statement they would be allowed to leave. Five confessed. And the police and prosecutors continued their charade knowing full well that details of the boys' made-up stories contradicted each other, that the one DNA sample taken from the victim didn't match any of the boys, that there was absolutely no forensic evidence tying them to the scene of the crime, and that there were legitimate questions about whether the boys had been at the scene of the crime at all.

"[They were] yelling at me all up in my face, poking me in my chest," says McCray of his interrogation. "We stopped a few times 'cause I was crying. They kept asking questions, no food, no drink, no sleep. I didn't know when it was going to end."

"I'm just going to make up something and include these guys' names," says Richardson, describing his thought process. "They was coaching me, and I was writing it down. They gave me the names, I put them in. I couldn't tell you who they were, what they looked like."

The Central Park Five were found guilty and sent to prison. In 2001, Wise — 16 at the time of the crime, sentenced as an adult, and still behind bars when the others had finished their time — ran into Matias Reyes, a serial rapist and murderer serving about 33 years to life. Reyes confessed to the crime to authorities. An ensuing investigation found that his DNA matched the lone sample found at the crime scene.

"I'm the one that did this," Reyes' recorded voice states in the film.

The exoneration of the five men never got the same amount of ink or air time that accompanied their capture and conviction. The message that they didn't do it was not nearly as sensational, couldn't possibly sell as many papers as the sordid tale of a 28-year-old white woman — an investment banker during the time when the financial industry had helped turn around New York City — being gang raped by a group of black and brown boys.

Newspaper headlines had disparagingly referred to them as a "wolf pack."

It's a terrible tale of what happens when police, a city, a nation jump onto a narrative of blame when the evidence doesn't support the accusations. Sadly, in this case and so many others, it's an ongoing narrative that paints young men of color as aggressive criminals, with the authorities, the media and the public all too ready to jump to false conclusions. One juror who appears in the film describes how his doubts were attacked by the other jurors until he finally gave in.

"If this had happened in 1901, they would have been lynched, perhaps castrated, and their bodies burned and that would have been the end of it," the Rev. Calvin Butts says in the film.

True, but what Butts doesn't connect is that in 2012 this kind of demonization continues. Just a few weeks ago in Jacksonville, Fla., a 45-year-old white man, Michael Dunn, shot into a car killing Jordan Davis, a black 17-year-old. The slain boy and his friends were sitting in a car in a convenience store parking lot listening to loud music when Dunn pulled in. Dunn complained about the noise and he and Davis argued. Dunn drew his weapon and shot eight or nine times into the vehicle, killing Davis. Dunn didn't report the incident to police. He went home and was only later found because someone had noted his license plate number. His lawyer says he felt threatened and acted in self-defense.

Most folks know about the killing of Trayvon Martin last February, when a self-appointed neighborhood watchman claimed he was standing his ground after he stalked and confronted the 17-year-old — who carried only a package of Skittles candy and a can of Arizona iced tea. When it comes to young men of color, it's all too easy to appoint yourself judge, jury and executioner on the spot.

That's why The Central Park Five is such an important movie. It's a reminder that anybody can be demonized at any moment and the results are usually tragic.

"Part of the underlying problem in this case are those racist assumptions that those kids must have been up to no good," says Burns of the Central Park Five. Her interest in the case started as a subject for her senior essay at Yale. She published a book on the subject in 2011. "That suspicion in 1989 made it so easy for people to believe this story even when it fell apart."

We're still pretty much playing by the same rules.

The Central Park Five opens Friday, Dec. 14, at the Main Art Theatre, 118 N. Main, Royal Oak, 248-263-2111.

See Jeff Meyers' review of The

Central Park Five in the Watch section of this week's paper.

Larry Gabriel is a writer, musician and former editor of Metro Times. Send comments to [email protected].