Is Charlie LeDuff really a philistine, or one of the savviest media personalities of our time?

American idiot

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Charlie LeDuff is in the news again.

The Fox 2 reporter is, of course, on the news, and has been since he took that post in 2010, but his particular brand of on-air performance art tends to blur the line between reporting the news and being the news.

This time LeDuff didn't set out to make a story, but he found himself at the right place at the right time — a nifty little habit of his — on Monday, May 18, when he was talking to American Coney Island owner Grace Keros outside of her restaurant.

A passer-by bumped into Keros as two of Detroit's most famous people chatted, snatching her cellphone out of her back pocket in the process. Keros yelled. LeDuff bolted after the thief, lurching his lithe 49-year-old frame in pursuit down Lafayette Boulevard before catching up with the culprit and tackling him to the ground.

LeDuff recounts the story to me the day after a segment on his heroics aired on Fox 2, offering some details that didn't make air, like this nugget: As the alleged perpetrator lay handcuffed on the side of the street, LeDuff got down at eye-level next to him and delivered a stern message.

"I took my sunglasses off, and I told him to remember my face," LeDuff says. "I told him, 'You don't mess with Charlie LeDuff!'"

By any metric, LeDuff stands out. He's a local reporter who doesn't look like a local reporter, eschewing the standard-issue industry ensemble of perfectly coiffed hair and suits for a slightly unkempt dark mop, goatee, and signature pair of cowboy boots, hand-painted with an American flag design.

Instead of the ubiquitous and familiar Midwestern lilt beaming from TVs across the country, LeDuff talks like a layman with an unplaceable accent that betrays his metro Detroit roots — it's somewhere between New York tough guy and vague Southern drawl.

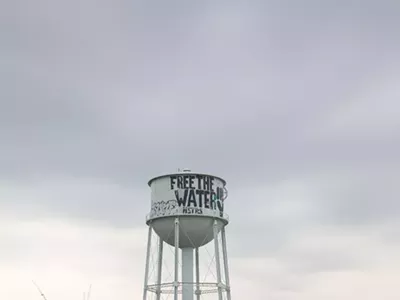

And when you watch a LeDuff segment, you instantly know it's a LeDuff segment. He's eaten cat food to illustrate Wayne County's abysmal Meals on Wheels program — a link to that segment on Reddit is titled "This guy is a reporter on Fox 2 here in Detroit. His name is Charlie LeDuff. He is fucking awesome." He's also golfed a stretch of Detroit to prove how empty it is, squatted in a house occupied by a squatter, and canoed down the polluted River Rouge. The intersection of news and entertainment has propelled those local video segments beyond metro Detroit and into the viral ether of the shareable news economy, the city itself as much a character in his segments as LeDuff.

When he returned to the city in 2008 to take a job with The Detroit News, he did so in part so that he could raise his daughter among extended family. But, as he wrote in his best-selling book, Detroit: An American Autopsy, he also came back because he thought Detroit would be the Next Big American Story. He was right. The national spotlight would soon focus on the city as the Kwame Kilpatrick scandal unfolded, the Big Three were bailed out, and the largest municipal bankruptcy in history went down. Detroit, to LeDuff, was something of a poster child for the economic malaise and racial tensions sweeping the nation.

And the nation tapped LeDuff as a sort of unofficial ambassador for the city in the process (or maybe LeDuff thrust himself on the stage). His best-seller helped, of course, as well as appearances on The Colbert Report and Real Time With Bill Maher to promote it. But Fox also took his oddball brand of reporting national in 2014 with The Americans, a segment syndicated to Fox stations across the country. And earlier this year, he became a regular contributor for Vice.

Which leads to the question of how LeDuff represents Detroit, and what he says about the media.

During a 2013 episode of Anthony Bourdain's food and travel show, Parts Unknown, LeDuff introduced the city to Bourdain as "post-apocalyptic, except for the fact that there's several hundred thousand people living here." Later in the episode, while discussing gentrification over dinner in an upscale pop-up, LeDuff spiked his soup with gin.

"Charlie LeDuff may have a Pulitzer Prize, but his appreciation of fine food and dining is, shall we say, lacking," Bourdain says in a voiceover. "Simply put, he's a philistine."

The first time I crossed paths with LeDuff was in a bar in Ferndale — his cowboy boots a dead giveaway. I nudged my girlfriend: "I'm pretty sure that's Charlie LeDuff."

My girlfriend recalled that her dad was a fan, and after we finished our drinks, we asked LeDuff for a photo.

I introduced myself as a Metro Times writer — and instantly winced, recalling that LeDuff was the subject of a critical MT story a few years ago. It centered on one of his most memorable and disseminated stories, a 2009 above-the-fold News piece titled "Frozen in indifference: Life goes on around body found in vacant warehouse." A four-column-wide photo of a dead man's legs sticking out from ice topped the article. Then-Metro Times news editor and current MT contributor Curt Guyette dug into the macabre tale of a dead homeless man and a basement hockey game and discovered omitted and sensationalized details in LeDuff's report.

The follow-up, "Anatomy of a Story," demonstrated LeDuff's propensity for making himself part of the news he covers. It wasn't that LeDuff got the story wrong — it was the nuance of the backstory that left some looking for more context. Either way, LeDuff was not pleased. Chances were good he was still not pleased.

Plus, I remembered LeDuff's tempestuous reputation otherwise — he was alleged to be involved in a St. Patrick's Day brawl in 2013 — and began to wonder if maybe this was a terrible idea after all.

But, thankfully, LeDuff shrugged the MT thing off and agreed to pose for a photo, but only if my girlfriend called her dad so he can talk to him.

"Hello?" LeDuff said after she put him on the phone. "You're speaking to Charlie LeDuff." The two engaged in a lengthy conversation. The bar was loud enough that we couldn't hear what LeDuff was saying, but he seemed to be enjoying the attention.

After the photo, I asked LeDuff about writing even after he'd made the transition to television personality.

"I like writing better," he said. "But it's hard to get people to read."

The line sticks with me, and weeks later I call LeDuff's office line to talk more about the art of journalism and his history for a profile in this rag. Affable and approachable at the bar, LeDuff is apparently hard to get ahold of on the phone.

"Hi, You've reached Charlie LeDuff," the pre-recorded voicemail message says. "Due to the volume of calls, please do me this favor: First state your name, then your number, and in one or two clear and very specific sentences tell me what's happening — and please forgive me, chances are I won't call you back; I just can't handle it all. But, I'll try. God bless, and bye-bye."

The CliffsNotes version of how LeDuff got here: He grew up with a mother, stepfather, three brothers, and a sister on Joy Road in Livonia. His mother worked in a flower shop on Detroit's east side. His stepfather left the family. His siblings dropped out of school. His sister occasionally worked as a prostitute and died after jumping out of a speeding van and hitting a tree.

As a writer, LeDuff's big break came when he got in at The New York Times on a 10-week minority scholarship (LeDuff is one-eighth Ojibwe). That turned into a 12-year career at the paper, where LeDuff cultivated a sort of blue-collar, everyman appeal, covering the hard-working and royally screwed.

The Pulitzer Prize comes from his 2000 contribution to a 10-part New York Times series called "How race is lived in America," in which LeDuff reported on race relations in North Carolina by embedding himself as a worker for a story titled "At a slaughterhouse, some things never die."

Often, his prose read more like hardboiled pulp fiction than sterile news copy; critics call it purple, or at times, "hackneyed." Still, his populist approach was well-received by readers, even if contemporaries and his editor weren't sold: "And at the Times, it is not the reader who matters so much," he wrote in American Autopsy. He quit while on paternity leave from the Times' Los Angeles bureau.

He came back to Detroit and enlisted at The Detroit News, where he would work for two years. (According to American Autopsy, LeDuff says he quit the News when his editors watered down a critical story about a judge in his coverage of the murder of Aiyana Stanley-Jones in 2010. LeDuff later published the details in a longform story for Mother Jones.) Back then, before video made Web-reporting what it is today, LeDuff was exploring the possibilities of the medium and doing LeDuff-type things.

For an early video assignment, he sat down with then-Detroit City Councilwoman Monica Conyers, notorious at the time for freaking out during a meeting and calling then-Council President Ken Cockrel "Shrek." In the clip, LeDuff asks Conyers point-blank if she is insane.

"If you were a nut — if you were a nut," he asks, sounding like a mock lawyer, "what kind of nut would you be?" He offers some suggestions: Pecan? Walnut?

"I'd be a peanut," he deadpans.

Conyers, apparently sufficiently disarmed, asks LeDuff why he would be a peanut.

"I like peanuts," he says. "Nobody doesn't like a peanut."

A few days after enjoying LeDuff's outgoing message, I get a call from a blocked caller ID. LeDuff seems like he isn't thrilled about my pitch for a profile — it turns out he is in fact still sore about the MT incident. Plus, he's done plenty of profiles already.

"What the fuck do I need another profile for?" he asks. "But you are you. I know you're a younger guy there."

He agrees to meet — but only if we talk about the art of journalism.

"If you're just gonna say some shit about me — I don't know what you're trying to do, but if it's a hit piece, be straight with me," he says. I assure him I'm not interested in a hit piece. "I've been run up before, and graciously so, but you move on. Nobody is battling for the soul of literary Detroit — that's the way I look at it. And by the way, it should be an art form."

I posit that perhaps that's precisely the reason he's such a polarizing figure in the local media — maybe his critics want him to stay in his lane, so to speak, to not fuck with the genre.

"Who's polarized? Ask yourself that," LeDuff says. "Is it really the public? It's the people in the business, isn't it?"

As for the rest of public opinion, he says he doesn't read online comments about himself. "There's an old saying, 'Never read your fucking clips,'" he says. "It could be the most awesome thing and 99 people love it. And this one person fucking stabs you, and you can't get over it. It's the one; it bothers you all day. You can't do it that way. You gotta just move on."

As an undergrad, LeDuff says he studied political science and economics at the University of Michigan. (He was also a U-M cheerleader while Jim Harbaugh was the quarterback. LeDuff filmed a recent segment with the new Wolverines coach and asked him if he deserves to be paid $5 million a year. Harbaugh admitted he's probably not worth it but refused to take a paycut. Later in the clip, a surprisingly spry LeDuff performs a toe touch and later, an impressive backflip.) I ask him what he did after, before he got into journalism. "Bumming around the planet all by myself," he says. "You see it, get confident, and start getting a worldview."

After he returned to the U.S., he says, he met a friend at a party who was heading for journalism school.

"I'm not a dummy, but I didn't really know there was such a thing as journalism school," he recalls. He soon enrolled in the University of California, Berkeley's journalism program. I ask if he got any encouragement for his writing before then. "Not really," he says. "I didn't really do much of it. I did, like, poetry and stuff, but no."

He pauses. "You're writing shit down, aren't you?"

He's on deadline and really does need to stop bullshitting and get to work, but he agrees to meet for drinks later that week.

"But don't make it tortuous, man," he says. "Despite what people think, I don't really like talking about myself much. It's weird. Think about it: It's what we do for a living, and someone does it to you."

LeDuff stands out indeed, and stands alone for the most part in what he does, and if he didn't want to talk about himself, we'd find others to talk about him instead.

For starters, an informal poll among media colleagues looking for a contemporary who treads the same ground in the same way comes up with no equivalents. One went further, recounting a rumor that Fox rounded up all of the company's local affiliate station reporters and played them a tape of LeDuff.

Alan Stamm, a Deadline Detroit contributor, "self-styled media critic," "Charlie-watcher," and Detroit News alum cites one specific piece of LeDuff tape as his jump-the-shark moment. It's the infamous one where LeDuff waits with a Detroit woman for hours after her home was burglarized to illustrate Detroit's slow police response times. During the wait, LeDuff picks up fast food, goes back after the woman says she doesn't want ice in her tea, and then takes a bubble bath. (As Devin Friedman surmised in a 2013 profile of LeDuff for GQ, one that named LeDuff "Madman of the Year," the video was "probably the only segment in the history of local network news in which producers at the station had to pixelize a reporter's balls.")

"It verges on self-parody sometimes," Stamm says. "There's other ways to show time passing. You can do a timelapse of a clock, or have your graphics department come up with something. So now, you're acting. ... Is it a news segment or a comedy skit?"

But Stamm concedes that without stunts like that, Deadline almost certainly wouldn't write about LeDuff. "It makes good water-cooler talk the next day," he concedes. "He's definitely shareable. He's definitely clickable."

Another colleague equates LeDuff's antics with the theatricality of Jon Stewart or Stephen Colbert, though those comparisons aren't perfect, either. Stewart is playing it straight, and Colbert is obviously playing a character.

Amanda LeClaire, a producer from metro Detroit who currently works for Arizona Public Media, calls it "Vaudeville journalism," but she doesn't mean that in a dismissive fashion. The gimmick allows LeDuff to go where other journalists might not be able to. "He's kind of like the court jester, you know — he can say some things other people can't say, under the guise of joking about it, or being sarcastic," LeClaire says before evoking an Oscar Wilde aphorism: "Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask and he'll tell you the truth."

But one gets the sense that LeDuff, even at his hammiest, isn't exactly putting on an act for the cameras. LeDuff is LeDuff.

"Charlie's a very kinetic personality. You never forget him," says Bill Shea, who covers media for Crain's Detroit Business. "He probably networks a little better than the rest of us. He doesn't need to leave behind a business card, because you're not going to forget that guy. His genuine personality is his own branding. I don't think it's contrived, which is refreshing and frightening at the same time. People think, 'Oh, he's not really like that.' He really is like that. He's not bullshitting. It's not an act at all."

The way that LeDuff gleefully breaks the unwritten (and antiquated) rules of journalism seems to be the crux of most of the criticism leveled against him. And, locally, there's some sentiment that LeDuff has contributed to the overwhelmingly negative media portrayal of the city. (In defense of focusing on the negative, as LeDuff writes in American Autopsy, "when normal things become the news, the abnormal becomes the norm. And when that happens, you might as well put a fork in it.")

An example of both: Earlier this year, the story of Detroit's "Walking Man" — James Robertson, a 56-year-old whose daily commute involved walking 21 miles to his factory job — went viral after the Detroit Free Press' original article. Soon after, a Wayne State student created a crowdfunding page for Robertson; more than $300,000 in donations poured in.

It was a rare, feel-good moment in Detroit media. But, in an Americans follow-up, LeDuff pointed out that Robertson's new fortune had now made him a target in his own neighborhood, to the point that Robertson had to enlist the protection of the police as he moved.

It wasn't until a day or so after the segment, in a column that would be his Vice debut, that we learned it was LeDuff himself who called the police on Robertson's behalf.

"Is it necessary for him to be a part of the story?" says Jesse Cory, who runs Detroit's Inner State Gallery and once worked as a photojournalist for WDIV. "The story doesn't exist without him being a part of it at that point."

LeDuff eventually does make good on his promise to get some drinks, suggesting we meet at Dino's, a watering hole on Ferndale's main drag, not far from his home in Pleasant Ridge.

He arrives wearing a motorcycle jacket, a button-down shirt, and the aforementioned cowboy boots.

I pull out my audio recorder and ask if LeDuff would mind if I recorded our conversation for my notes — and am somewhat surprised when he says he would. "Sometimes I run my mouth," he shrugs. I can't help but find it funny that a guy who has no problem taking his pants off on television (repeatedly) would be wary of oversharing.

As LeDuff nurses a Bell's Two-Hearted Ale, I ask him to elaborate on what he said when I first met him, about preferring writing over TV.

"I love writing — hard, real writing," he says. He says he still believes in the concept of "the great American longform feature," though outlets for that sort of journalism are drying up.

LeDuff explains that video and writing have their own strengths — with a written story, he can include the hard facts, the stuff you can't capture with video. The Vice columns, he says, are meant to complement The Americans segments; they are no mere transcriptions. "They augment each other," he says.

People crave stories, LeDuff says, told in a structured way. He offers a theory why most evening news stories are about murder: "Murder has a natural climax: The guy died."

He cites the Fox 2 clip where he waited with the woman for the police to show up. "I could have communicated the same information by reading off a list of police response times," he says. "But that would be boring."

LeDuff shares his plans for his next segment, which he will soon film on the East Coast. Washington, D.C., and Wall Street, he explains, are two "Towers of Power" in the U.S. There are only four stops between the two destinations via rail: Baltimore; Wilmington, Delaware; Philadelphia; and Newark, New Jersey.

"I'm going to be riding on the train, and there's elevator music playing," LeDuff says, pantomiming reading a newspaper and humming. "Then I get off in Baltimore — and there's people marching."

In conversation, it can be hard to keep up with LeDuff, who moves from one subject to the next before you can even be sure you're both talking about the same thing. "I've been saying this lately: You can't have 'peace' without 'piece,'" he says as I nod, scribbling the quote down without any context.

I ask LeDuff when he realized he was good behind a camera. His TV work, he says, goes back to his Berkeley days — in school, he took TV 101, and documentary 101, and so on.

I ask about the Fox affiliate rumor. LeDuff looks surprised and amused.

"And when did this conference allegedly occur?" he asks, once again sounding like a mock lawyer. "This is all I'll say about that: I work for Fox News, not just Fox 2," he says. What that means is he pretty much has complete creative control to do whatever he wants. The Americans is syndicated, and Fox affiliates can edit it however they want to fit into their local programming.

LeDuff gets up for a smoke, stretching his arms in an exaggerated basking gesture. "When the zephyr blows, you just have to enjoy it," he says. His wife and daughter are waiting for him at home. He's going to watch the original RoboCop for the first time tonight, having picked up on comparisons of the film's dystopian corporate-controlled Detroit to the real-life Detroit of today. "Speaking of art," he says. "There's life imitating art right there." (Later, I ask LeDuff if he liked RoboCop. He says he fell asleep. "Doesn't hold up. The script wasn't tight.")

I ask him about Bourdain's "philistine" quip. LeDuff admits he was hamming it up for the cameras. "I'm like, 'Why's Bourdain want me to be here?' I had to give him something," he says. "He was just razzing me, like guys do." It's not the first time LeDuff served as a Detroit consultant for a film project: He says he also worked behind the scenes helping Bjork's husband shoot around Detroit. ("That guy was a dick," he says.)

LeDuff has, by this point, accumulated a small circle of drinking buddies. At one point, he offers a patron an entire beer in exchange for one chicken wing. He orders a round of Jägerbombs in Spanish, despite the bartender insisting he doesn't speak Spanish.

There are no cameras rolling: LeDuff is the star of a show that people may or may not be watching. Later, he offers me a cigarette and tries to convince me not to do a profile on him after all.

My notes from the bar are a total mess. LeDuff made a passing offer to chat again after they filmed the train stuff. Several weeks later, he comes through, and we meet for coffee.

LeDuff is dressed in jeans, a black sweater, and a black scarf. Objectively, he looks like an artiste. LeDuff takes his coffee black.

I can't help it: I ask about the cowboy boots. "These are version 3.0," he explains. His wife made his first pair; the second was donated to an auction. The current pair look beat-up, hand-painted to cover up scuff marks.

A group of Canadian fans interrupt and ask LeDuff to pose for a photo. Like my girlfriend did, one of them mentions his dad is a fan. I begin to get the impression that on any given day, LeDuff is told by many people how much their dads like him. LeDuff agrees to pose for a photo, this time without asking the guy to put his dad on the line. They also ask about the boots, and LeDuff repeats the same explanation he gave to me minutes before.

Eventually, the fans leave and LeDuff plays the train clip. Following the recent riots in Baltimore, his bosses postponed the clip by a week in order to give a sensitive subject a cooling-off period. But a different news story added an unexpected and tragic dimension to the piece: On May 12, four days after LeDuff arrived, an Amtrak train derailed in Philadelphia, killing eight and injuring 200.

The challenge with The Americans, LeDuff says, is cutting hours of footage down into a five-minute clip. And there's no script: With only the conceit of taking the train from Washington to Wall Street, LeDuff and his crew had a limited time to get off at each stop and find something interesting to film. For any given segment, LeDuff says there are hours of footage that don't get used.

"These cities, the largest in their respective states, used to be rich," LeDuff says in a voiceover. "Now they're among the poorest and most violent in the country: The Corridor of Pain."

He gets off at the first stop in Baltimore. By the time LeDuff arrives, there are no longer any protesters. The footage cuts to the riots from late April, a month before.

LeDuff gets out at each stop and talks to people, ending nearly every encounter with a combination handshake-hug. In Baltimore, a white police officer tells LeDuff not to film as he tries to disperse a group of black men. LeDuff asks both the cop and the black men if they're rich: They all answer no.

In Philadelphia, LeDuff talks to a mother whose children aren't allowed to bring their textbooks home from school due to a shortage. He then shows footage of tens of thousands of textbooks rotting in a warehouse.

"Something's not right in regular America. No money, no jobs, bad schools, crumbling infrastructure," he says at the close of the clip. "As one goes, we all go. E pluribus unum."

LeDuff asks me for a critique. I tell him the police officer shot is awkward, occupying one continuous shot that lasts nearly a minute.

He admits it's a long stretch for TV, but defends the choice. There was a second camera on the scene, he says, but they weren't able to cut to it because of a malfunction. Besides, there are so many interesting moments within the scene, "it makes for good cinéma-vérité," he says.

The segment alone could have been split into four, one for each stop, or even lengthened into a short documentary. The five-minute bookend is limiting in a way, even if it's comparatively chunky by TV news standards. I ask LeDuff if he's ever considered making a documentary film, a la Michael Moore.

"If you're a documentarian, you have a core audience," he says. "Some documentaries occasionally cross over — like Roger & Me — but they still have a limited audience. I want to have mass appeal."

A five-minute clip is punchy and shareable, long enough to include the minimum necessary information yet short enough to hold the average viewer's attention span. LeDuff says he likes the immediacy of the impact of the shorter clips: "If my brother calls me up after a clip airs," he says, "I know I hit a home run."

LeDuff's crew is small: Matt Phillips and Bob Schedlbower serve as photographers and editors. Deb Andrews serves as producer, "a jack of all trades," handling business, promoting stories, and logging tapes.

They used to fight with the bosses over edits, but not so much anymore.

"I used to fight all the time," LeDuff says. "Now, I let it go. I don't care." Besides, the unedited versions are available as originally edited on a portal website for The Americans. "It's art in a corporate context," LeDuff admits.

He mentions an early assignment at Fox 2, a mundane report on unshoveled sidewalks in the winter — typical nightly news fodder.

"I was like, are you kidding me?" LeDuff says. "I have a fucking Pulitzer!"

So LeDuff gave it the LeDuff touch. In the clip, he pretended to slip on the ice. A caption flashes: "Dramatization." LeDuff flails around dramatically: "Overdramatization."

"Some redneck guy was watching and he was like, 'Hmm, slow news day?'" LeDuff says. "These people know every bell and whistle of the media." So instead, LeDuff goes for self-reflexivity. "I try to show them that I'm in on the joke," he says.

In that sense, maybe critics are wrong to judge LeDuff as a reporter. Perhaps LeDuff is in fact the world's premier postmodern reporter.

For a 2008 story in Vanity Fair, LeDuff accompanied famed photographer Robert Frank on a trip to China. In the piece, LeDuff comes across as anything but a philistine, namechecking New American Cinema, Jack Kerouac, and paintings of Wassily Kandinsky.

Frank was in China to exhibit photos from his seminal book, The Americans, which was originally published 50 years before. The book contained raw black-and-white portraits of subjects he met on road trips — "old angry white men, young angry black men, severe disapproving Southern ladies, Indians in saloons, he/shes in New York alleyways, alienation on the assembly line, segregation south of the Mason-Dixon line, bitterness, dissipation, discontent," as LeDuff wrote for VF, or "83 daggers which he plunged directly into the heart of the Myth."

LeDuff seems to share more than just the name of his show with Frank's The Americans. Like Frank, his preferred subjects are the everyday characters he meets across the country. Like Frank, he's a magnet for extremes. And like Frank, LeDuff seems to be critical of the American Dream.

When I asked MT columnist and Wayne State University journalism professor Jack Lessenberry about LeDuff, he referenced "The Idiot Culture," a 1992 New Republic essay by Watergate journalist Carl Bernstein that lamented the decline of serious journalism in favor of amusing, ratings-based media. The ancient Romans might have had their own phrase for the same phenomenon: bread and circuses.

Entertainment or education is the simple version of the debate. When LeDuff eats a can of cat food on TV, do viewers remember why? Or do they just remember that he ate cat food?

Police response times have plummeted since he and others covered the lag. Conyers eventually resigned from City Council, and was later jailed for bribery. The squatter is serving a probationary sentence for assault with a dangerous weapon. Robertson is safe. And Keros got her cellphone back.

People are watching, whether they think LeDuff is an American, or an American idiot.

Staff writer Lee DeVito opines weekly on arts and culture for the Detroit Metro Times.