In a draft subpoena petition obtained by The Intercept, Flint special prosecutor Flood, who was appointed by then-Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette in 2016 to carry out the original Flint water investigation, sought to interview Jim Fick, a state IT official with the Department of Technology, Management, and Budget (DTMB). In the subpoena petition, Flood referenced the top MDHHS officials from whom he had recently obtained phone data; four out of their five phones had "no records prior to October 2015."

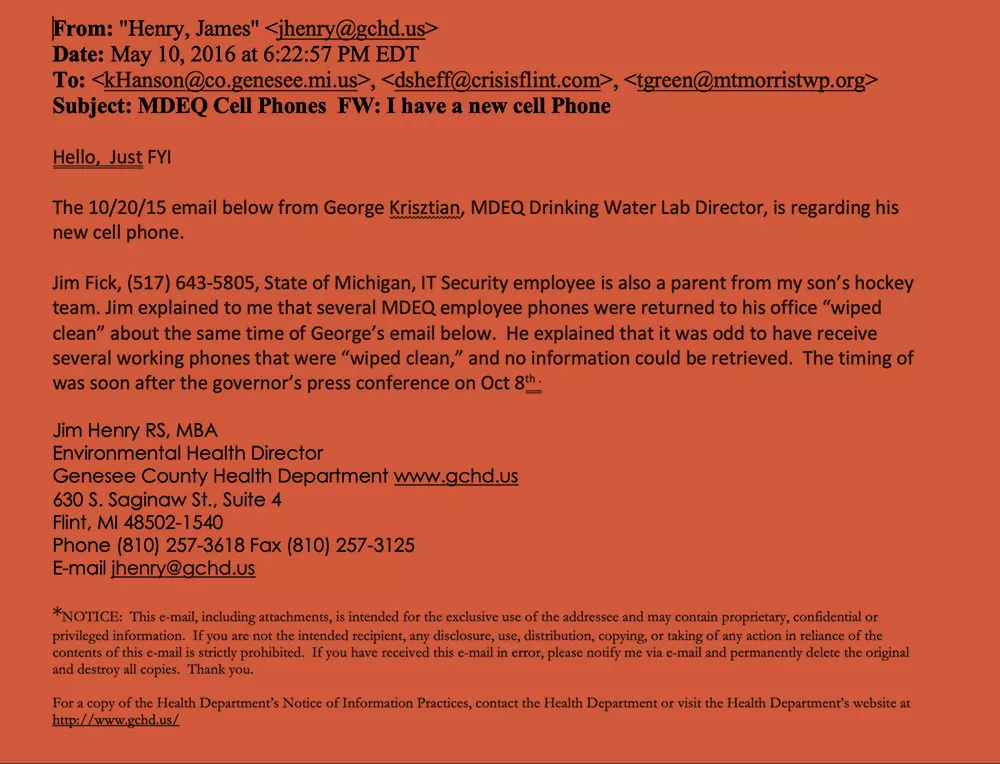

Flood's subpoena motion also described an email that he and his criminal team received in May 2016 from Jim Henry, a supervisor with Genesee County Health Department, who knew Fick through their children's hockey team. In Henry's email, obtained by The Intercept, he wrote: "Jim [Fick] explained to me that several MDEQ [Michigan Department of Environmental Quality] employee phones were returned to his office 'wiped clean' about the same time of George's email below."

Henry was referring to George Krisztian, who served as MDEQ's lab director involved with Flint's water lead- and copper-testing data — data that Flint water investigators found MDEQ officials had "conspired" to alter in order to bury the true lead levels that showed Flint's water was toxic.

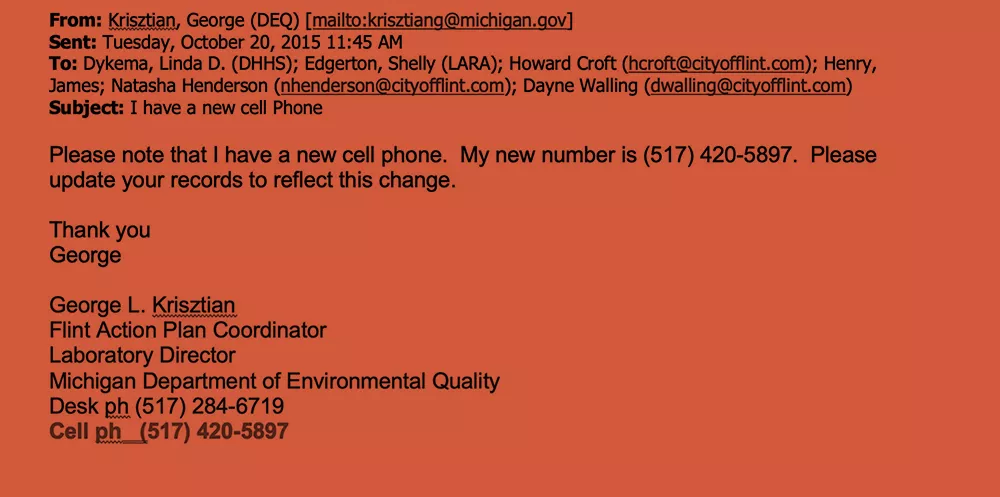

Soon after Snyder's Oct. 8, 2015 press conference announcing Flint's water was toxic, Krisztian was named MDEQ's Flint action plan coordinator. Weeks later, on Oct. 19, 2015, MDEQ director Dan Wyant admitted that the state environmental department had erred when it failed to treat Flint's water with corrosion-control chemicals that prevent lead from leaching off old distribution pipes into the city's water supply. One day after MDEQ's public mea culpa, Krisztian sent an email to colleagues announcing that he had a new cell phone and number.

Henry told prosecutors that Fick explained "it was odd to have [received] several working phones that were 'wiped clean' and no information could be retrieved. The timing of [this] was soon after the governor's press conference on the 8th." It was at that press conference that Snyder had first spoken publicly of the alarming lead levels. (The Intercept does not know which MDEQ officials allegedly used these phones or whether they are connected in any way to the senior MDHHS officials' phones described by Flood as missing any data prior to October 2015.)

Krisztian told The Intercept that he got a new phone shortly after Snyder's press conference because of "my new assignment as the Flint Action Plan Coordinator."

"I needed a phone that was dedicated to that job so that the Lab could get their phone back and be used by the acting lab director," he said. "Many parties had that phone number as a contact for the lab, and if I recall correctly that number was also used for emergency response efforts. As such, it was only logical that I be issued a new phone and number. In addition, the old phone was a flip phone that had very limited functionality and a smartphone was much better suited to handle the needs of the Flint assignment."

In general, getting a new phone and a new number was unusual, the former state official with DTMB familiar with government data preservation told The Intercept.

"If you were supposed to get a new phone, even if it was an upgrade, you would keep the same number," the ex-DTMB official said. "That's the number on your business card and on all your documentation, so they wouldn't change that."

Krisztian aside, Flood considered whether there was a connection between the "wiped clean" phones and the phones he described with missing data, writing, "The contents of the imaged data [from MDHHS officials' phones] have given credence to the possibility that was articulated from James Fick to James Henry may have occurred."

Despite the petition to subpoena Fick, Flood's team was never formally able to interview the IT official under oath, The Intercept learned; the subpoena petition moved up the attorney general's leadership chain, but the "brakes kind of got pumped" and efforts to subpoena Fick halted, a source familiar with the chain of events told The Intercept. Instead, an investigator spoke with Fick informally, the results of which are unknown.

Fick did not respond to multiple requests for comment from The Intercept regarding Henry's tip to investigators. Henry, too, did not respond.

At least one high-level MDEQ official was asked to hand in his state-issued phone in the same October 2015 period that Fick allegedly received several "wiped clean" phones, documents obtained by The Intercept reveal.

In a confidential 2016 interview, Jim Sygo, then-MDEQ deputy director, told Flood that sometime in October 2015 he was asked to give his phone to Mary Beth Thelen, the administrative assistant to MDEQ director Wyant, documents obtained by The Intercept show.

"I don't know where they took it or what they did with it," Sygo told Flood in a confidential interview, adding that he believed they were taking his phone to have it imaged. When Flood asked him if he received his phone back after handing it in, Sygo answered no. He did not specify whether he was given a new phone.

Sygo, who died in 2018 eight months after he testified in the pre-trial of Michigan's chief medical executive Wells, was an MDEQ official who investigators questioned to find out what and when MDEQ director Wyant — and Snyder — knew about Flint's deadly waterborne Legionnaires' Disease outbreak.

When approached about the alleged "wiped clean" phones delivered to Fick, a DTMB spokesperson told The Intercept: "Each agency has a designated smart device coordinator who is responsible for ensuring their agency devices follow all IT security policies, guidelines, procedures, practices and recommendations. When an employee departs state service, their device should be returned to the coordinator, who then ensures the phone is properly handled. State agencies and their smart device coordinators are responsible for determining when to securely wipe the device. DTMB provides technical guidance on how to securely wipe the devices. Questions about agency actions with mobile devices need to be addressed by the specific agency."

A spokesperson for MDEQ, which has rebranded itself the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, pointed to the previous Snyder administration.

"The current administration [of Governor Gretchen Whitmer] is neither in a position to confirm the actions of, nor speculate on the motives of, employees and former employees that occurred six years ago," they said. The spokesperson declined further comment, citing the ongoing Flint criminal investigation.

Beyond the questions arising from the phone data, The Intercept uncovered more details behind multiple internal investigations Governor Snyder initiated into the Flint water crisis. One of the investigations — led by the Michigan State Police (MSP) to investigate MDEQ's culpability for the water crisis — was launched on the same day AG Schuette announced Flood as the Flint criminal investigation's special counsel in January 2016.

The other Snyder-launched investigation was led by the state inspector general/auditor general investigating MDHHS' role in the water crisis. In a sharply worded May 25, 2016 letter Schuette sent to Governor Snyder, the attorney general ridiculed the investigations, arguing that they "have compromised the ongoing criminal investigation" and "may effectively be an obstruction of justice."

After Schuette's letter demanding that Snyder cease his own Flint investigations, the governor announced a halt to them.

The Intercept obtained a draft of Schuette's letter from a week before it was sent to Snyder that indicates the final letter was softened compared to the draft shortly before it; the previous draft had indicated the attorney general believed Snyder's internal investigations weren't credible.

"The failure to halt your ongoing civil and administrative 'investigations' may cause the guilty to go free, obstruct justice, and result in gross injustice to the families of Flint and to the families of Michigan," the May 19, 2016, draft said.

"The AG wanted quotes around the word investigations in that paragraph; I don't know if he wanted that usage throughout," retired Judge William Whitbeck, a member of the Flint criminal investigation team, wrote to colleagues in a May 19, 2016 email obtained by The Intercept.

But in the final letter sent by Schuette to the governor on May 25, 2016, the quotation marks around investigations were removed. Another notable change from the draft letter was the removal of a section in which Schuette suggested that Lt. Lisa Rish, who led MSP's investigation into MDEQ's role in the water crisis, obtained "coerced statements" from MDEQ employees that the Supreme Court's Garrity v. New Jersey decision outlawed.

"Garrity issues of this type have the potential to complicate, and in fact have already complicated, our ability to conduct the type of thorough and timely criminal investigation that the Flint water crisis demands," the May 19, 2016, draft said. But in the final letter, mentions of the Garrity Supreme Court decision and "coerced statements" were removed.

Beyond the changes in the final letter sent to the governor, Snyder's top adviser and self-described "fixer," Richard Baird, was the point-person for Snyder who engineered the state police and inspector general/auditor general investigations, multiple sources familiar with the criminal investigation told The Intercept. With this knowledge in mind, Schuette copied Baird on the letter to the governor, along with Snyder's private attorney, chief legal counsel, and chief of staff.

In January, Baird was charged with obstruction of justice, misconduct in office, perjury, and extortion for his role in the Flint water crisis.

The attorney representing Baird did not respond to The Intercept's request for comment.

The state police investigation's report, obtained by The Intercept, minimized MDEQ's culpability in the water crisis. In the report, MSP Lt. Lisa Rish wrote that MDEQ employees she interviewed "denied any wrongdoing" and claimed they had followed federal drinking-water regulations while making decisions related to Flint's water. MSP interviewed 11 MDEQ officials, four of whom ended up being charged by AG Schuette as part of the Flint water criminal investigation.

In one example, Lt. Rish wrote that MDEQ supervisor Stephen Busch merely made a "misstatement" when he falsely told concerned EPA officials that Flint had an "optimized corrosion control program" in February 2015. As the Detroit Free Press reported, Flint "disastrously" had no corrosion control program in place at all, the lack of which resulted in lead leaching off of the city's older pipes into its drinking water.

Schuette did not respond to The Intercept's request for comment, nor did Lt. Rish or the Michigan State Police.

Snyder's internal investigations weren't the only red flags investigators discovered surrounding the governor and his top adviser, Baird.

The Intercept learned that departments, including MDEQ and MDHHS, were tasked with creating timelines for their respective actions during the water crisis. But like many other things inside the Snyder administration during the crisis, the timelines were routed through Baird, who was well-known in state government as Snyder's right-hand man and close friend dating back to when Baird gave the governor his first job out of college.

Baird's power as the governor's point-man even drew jokes of him being a "shadow governor."

Upon reviewing the timelines, Flood's investigators determined the state departments had omitted important facts and events, according to documents reviewed by The Intercept; more so, they learned the timelines were routed through Baird. Documents related to Flood's investigation accuse Baird of inserting false information into the timelines in order to provide state officials with an official story to tell if and when they were questioned over the water crisis.

More than just allegedly false information, the timelines seemed to be missing important events linked to the water crisis.

"It appears that MDEQ has missed a few items," Henry, the Genesee County Health Department supervisor who sent prosecutors the tip about the "wiped clean" phones to investigators, wrote in a Dec. 3, 2015, email to colleagues that attached the Flint water timeline MDEQ put together.

"I doubt they want our help filling in the blanks," Henry wrote.