This story was produced in a partnership between The Intercept and Detroit Metro Times.

In October 2015, then-Michigan Governor Rick Snyder finally announced that Flint's water was contaminated with dangerous lead levels. That public admission had come after more than a year of pleading from the city's residents to examine the situation. The city, Snyder promised, would immediately stop using water from the Flint River, which residents had been drinking for 18 months.

The public announcement raised as many questions as it answered, and kick-started a years-long investigation into how the decision that delivered the toxic water to Flint had been made in the first place, how many people were sickened and killed as a result, and when senior government officials first learned of the deadly consequences.

Along the way, however, investigators who were part of a three-year Flint water investigation beginning in 2016 kept drilling dry holes.

Dr. Eden Wells became Michigan's chief medical executive in May 2015. By then, the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services had been aware for at least seven months about a significant increase in the deadly waterborne Legionnaires' Disease throughout Flint.

But when investigators obtained access to Wells's phone, they discovered something unusual. "For Dr. Wells' phone the earliest message is from November 12, 2015," then-Flint special prosecutor Todd Flood wrote in a subpoena petition obtained by The Intercept. During the key period that investigators were probing, no messages were found. In 2018, a judge ruled Wells would have to stand trial for involuntary manslaughter, along with obstruction of justice, over her role in the water crisis. (Those charges were dropped by current Attorney General Dana Nessel in 2019; in January 2021, Nessel's Flint water prosecutors recharged Wells with involuntary manslaughter, misconduct in office, and neglect of duty.)

Other searches turned up similar results. The phone of Tim Becker, MDHHS's chief deputy director, had no messages on it prior to April 14 2016, two months before he left his role with MDHHS, the subpoena reported. Becker testified to having first asked questions about Flint's Legionella outbreak in January 2015.

Patricia McKane, an epidemiologist with MDHHS who testified that she was pressured to lie by Dr. Wells about elevated blood-lead levels in Flint's children, was found to have only had four text messages on her phone from 2015 and seven total messages. (Wells denied the allegation.) Fellow MDHHS epidemiologist Sarah Lyon-Callo, who Dr. Wells copied in an email responding to accusations by a Wayne State University professor that she was trying to conceal the link between the Flint River switch and the Legionella outbreak, had no messages prior to June 2016.

"Again, for some strange reason the earliest text message in time on her device begins June 20, 2016," reads the subpoena petition. Wesley Priem, manager of the MDHHS's Lead and Healthy Homes program, who emailed colleagues erroneously challenging the findings of high blood-lead levels in Flint children discovered by Flint pediatrician Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, had just one text message found on his state-issued phone from Jan. 22, 2016.

The missing phone messages from top MDHHS officials were a major red flag to investigators and an obvious impediment to those investigating who knew what and when. Despite department epidemiologists hypothesizing in October 2014 that the source of Flint's deadly Legionnaires' Disease outbreak was the switch to the Flint River six months earlier, Flint residents weren't informed of the deadly outbreak until 16 months later when Governor Snyder announced it in January 2016. PBS found a 43 percent increase in pneumonia deaths in Flint during the 18 months the city received drinking water from the Flint River — and also found that scientists believed some of those 115 pneumonia deaths could be attributed to Legionnaires' Disease, which has similar symptoms to pneumonia and is often misdiagnosed as such.

Investigators also discovered that phone data belonging to a key official close to Governor Snyder was completely erased shortly before the Flint criminal investigation was launched.

Sara Wurfel, Governor Snyder's press secretary during the water crisis in 2014 through fall 2015, told Flood her phone was "wiped" when she left her job at the end of November 2015 — after a civil suit was filed against the Snyder administration and a month before the launch of the Flint water criminal investigation.

"Do you have text messages from 2015 currently [on your phone]?" Flood asked Wurfel in a confidential interview obtained by The Intercept.

"No. So when I left the Governor's office, everything got wiped. I mean, when – I turned in my phone, it got wiped," Wurfel told Flood. Wurfel, who kept her state cell number when she left her government job, said she didn't recall if she had been asked to hand in her phone at any other time in 2015 prior to leaving her job in November. She also said she didn't think she had used iCloud to back up her phone data.

When asked for comment by The Intercept, Wurfel said, "Not sure what you're referring to — please share if there's a specific document, item, etc." When provided with what she told the special prosecutor regarding her phone being wiped when she left her state role, she did not reply.

"That is not standard," a former Department of Technology, Management and Budget [DTMB] official who worked for the state during this period and was involved with state data preservation told The Intercept about Wurfel's phone being wiped upon leaving her role as Snyder's press secretary. "There are retention schedules that every agency, including the governor's office, is supposed to adhere to," said the ex-official, adding that for the governor's office, data is supposed to be retained for at least a year after an official leaves. But with potential litigation looming, "it should've been held indefinitely," the official concluded. The source spoke only on the condition of anonymity for fear of professional retaliation.

As the water crisis intensified, criminal prosecutors and investigators would discover that messages were missing from before October 2015 on phones belonging to top MDHHS officials.

tweet this

Lonnie Scott, the executive director of the progressive organization Progress Michigan, told The Intercept "it's not entirely surprising to hear" that top officials' phones were altered or wiped completely. Scott had seen something similar happen before in 2014 when his organization had submitted Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests for state health director Jim Haveman's communications with Snyder's chief of staff. After Haveman resigned from his job in October 2014, Progress Michigan discovered that his emails were deleted upon his resignation from his role.

"We've said all along that we believe that there was a cover-up and that the governor knew more information than he was putting out publicly," Scott said.

The Intercept has also learned that former prosecutors were told that phones belonging to officials with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) might have been erased.

Soon after Snyder's October 2015 announcement about Flint's toxic water, the heat intensified around the governor as calls for a federal investigation into the water crisis mounted along with heightened media attention. As the water crisis intensified, and a criminal investigation was launched, criminal prosecutors and investigators would discover that messages were missing from before October 2015 on phones belonging to top MDHHS officials.

The question of what Snyder knew and when, and what role he and his administration played in stymying investigations into the cause and cover-up of the outbreak, is of increasing importance as the former governor now faces trial in connection with his handling of Flint's water crisis.

Wells's lawyer did not respond to The Intercept's request for comment. Neither did Becker, McKane, Lyon-Callo, or Priem. A spokesperson for Governor Snyder declined to comment.

On the missing phone messages from top MDHHS officials, a department spokesperson told The Intercept, "The department does not care to comment other than to say that the department always cooperates with the Attorney General's office in providing anything that office has asked for during its Flint water investigation."

Governor Snyder's legal team declined to comment.

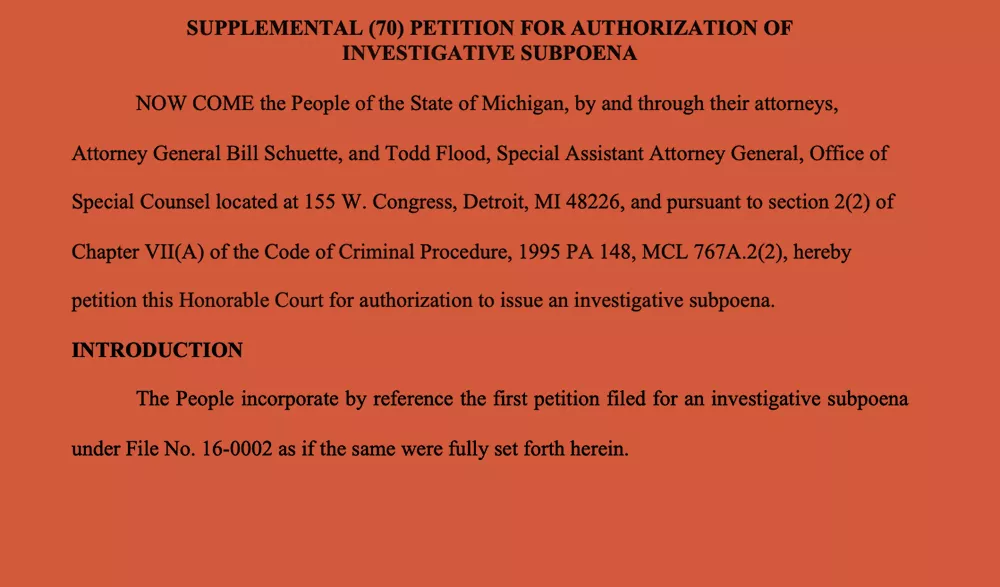

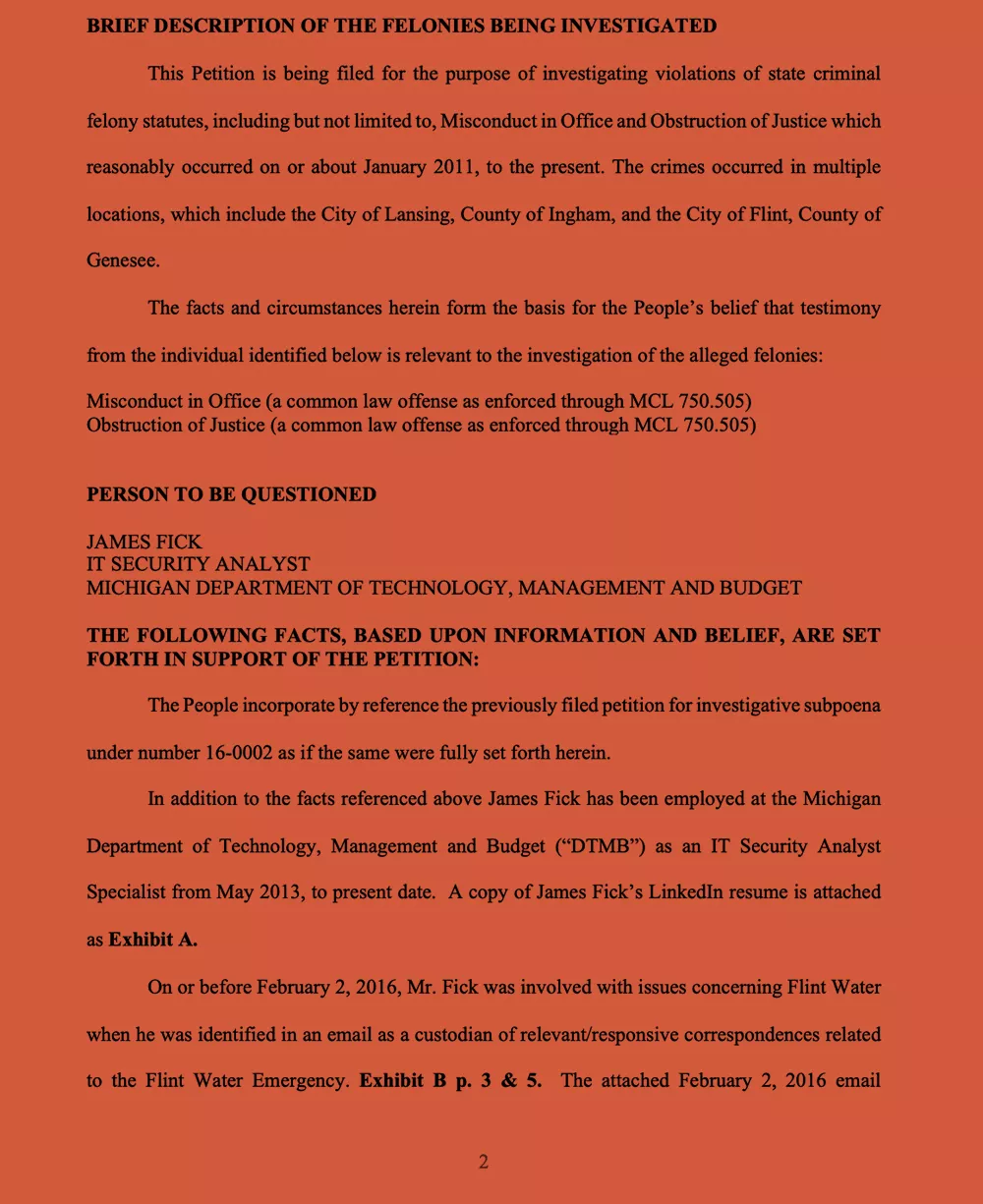

In a draft subpoena petition obtained by The Intercept, Flint special prosecutor Flood, who was appointed by then-Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette in 2016 to carry out the original Flint water investigation, sought to interview Jim Fick, a state IT official with the Department of Technology, Management, and Budget (DTMB). In the subpoena petition, Flood referenced the top MDHHS officials from whom he had recently obtained phone data; four out of their five phones had "no records prior to October 2015."

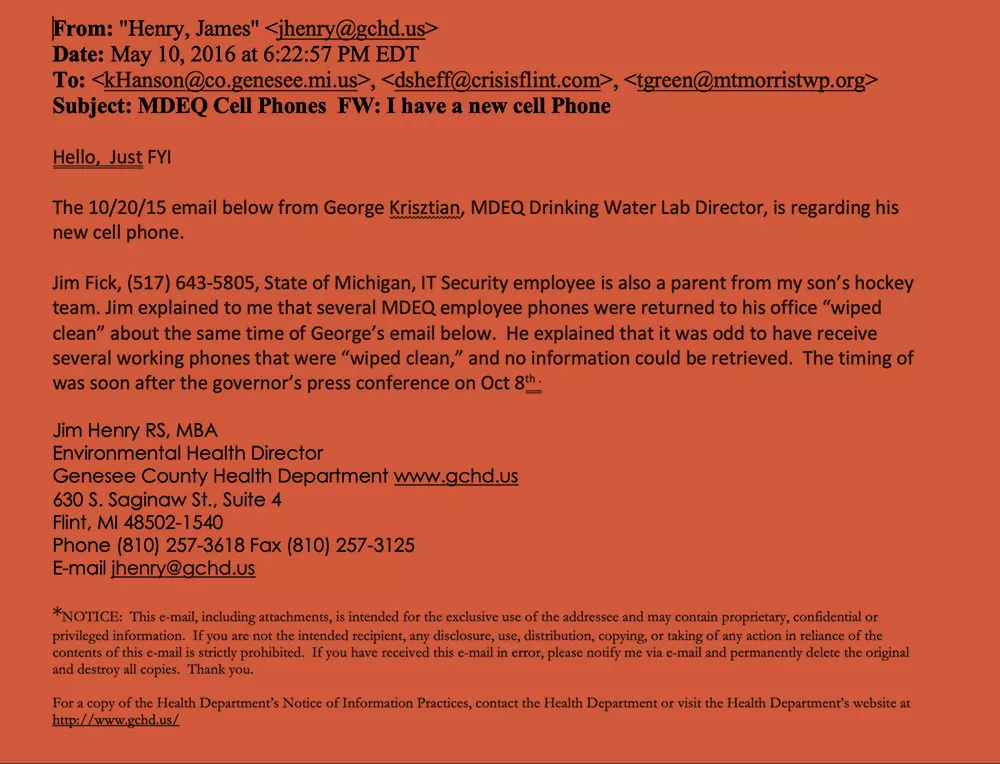

Flood's subpoena motion also described an email that he and his criminal team received in May 2016 from Jim Henry, a supervisor with Genesee County Health Department, who knew Fick through their children's hockey team. In Henry's email, obtained by The Intercept, he wrote: "Jim [Fick] explained to me that several MDEQ [Michigan Department of Environmental Quality] employee phones were returned to his office 'wiped clean' about the same time of George's email below."

Henry was referring to George Krisztian, who served as MDEQ's lab director involved with Flint's water lead- and copper-testing data — data that Flint water investigators found MDEQ officials had "conspired" to alter in order to bury the true lead levels that showed Flint's water was toxic.

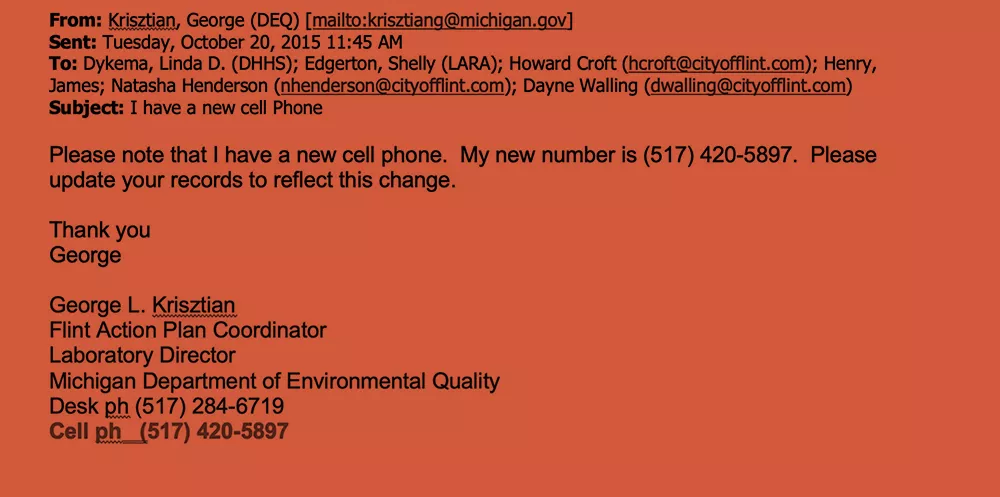

Soon after Snyder's Oct. 8, 2015 press conference announcing Flint's water was toxic, Krisztian was named MDEQ's Flint action plan coordinator. Weeks later, on Oct. 19, 2015, MDEQ director Dan Wyant admitted that the state environmental department had erred when it failed to treat Flint's water with corrosion-control chemicals that prevent lead from leaching off old distribution pipes into the city's water supply. One day after MDEQ's public mea culpa, Krisztian sent an email to colleagues announcing that he had a new cell phone and number.

Henry told prosecutors that Fick explained "it was odd to have [received] several working phones that were 'wiped clean' and no information could be retrieved. The timing of [this] was soon after the governor's press conference on the 8th." It was at that press conference that Snyder had first spoken publicly of the alarming lead levels. (The Intercept does not know which MDEQ officials allegedly used these phones or whether they are connected in any way to the senior MDHHS officials' phones described by Flood as missing any data prior to October 2015.)

Krisztian told The Intercept that he got a new phone shortly after Snyder's press conference because of "my new assignment as the Flint Action Plan Coordinator."

"I needed a phone that was dedicated to that job so that the Lab could get their phone back and be used by the acting lab director," he said. "Many parties had that phone number as a contact for the lab, and if I recall correctly that number was also used for emergency response efforts. As such, it was only logical that I be issued a new phone and number. In addition, the old phone was a flip phone that had very limited functionality and a smartphone was much better suited to handle the needs of the Flint assignment."

In general, getting a new phone and a new number was unusual, the former state official with DTMB familiar with government data preservation told The Intercept.

"If you were supposed to get a new phone, even if it was an upgrade, you would keep the same number," the ex-DTMB official said. "That's the number on your business card and on all your documentation, so they wouldn't change that."

Krisztian aside, Flood considered whether there was a connection between the "wiped clean" phones and the phones he described with missing data, writing, "The contents of the imaged data [from MDHHS officials' phones] have given credence to the possibility that was articulated from James Fick to James Henry may have occurred."

Despite the petition to subpoena Fick, Flood's team was never formally able to interview the IT official under oath, The Intercept learned; the subpoena petition moved up the attorney general's leadership chain, but the "brakes kind of got pumped" and efforts to subpoena Fick halted, a source familiar with the chain of events told The Intercept. Instead, an investigator spoke with Fick informally, the results of which are unknown.

Fick did not respond to multiple requests for comment from The Intercept regarding Henry's tip to investigators. Henry, too, did not respond.

At least one high-level MDEQ official was asked to hand in his state-issued phone in the same October 2015 period that Fick allegedly received several "wiped clean" phones, documents obtained by The Intercept reveal.

In a confidential 2016 interview, Jim Sygo, then-MDEQ deputy director, told Flood that sometime in October 2015 he was asked to give his phone to Mary Beth Thelen, the administrative assistant to MDEQ director Wyant, documents obtained by The Intercept show.

"I don't know where they took it or what they did with it," Sygo told Flood in a confidential interview, adding that he believed they were taking his phone to have it imaged. When Flood asked him if he received his phone back after handing it in, Sygo answered no. He did not specify whether he was given a new phone.

Sygo, who died in 2018 eight months after he testified in the pre-trial of Michigan's chief medical executive Wells, was an MDEQ official who investigators questioned to find out what and when MDEQ director Wyant — and Snyder — knew about Flint's deadly waterborne Legionnaires' Disease outbreak.

When approached about the alleged "wiped clean" phones delivered to Fick, a DTMB spokesperson told The Intercept: "Each agency has a designated smart device coordinator who is responsible for ensuring their agency devices follow all IT security policies, guidelines, procedures, practices and recommendations. When an employee departs state service, their device should be returned to the coordinator, who then ensures the phone is properly handled. State agencies and their smart device coordinators are responsible for determining when to securely wipe the device. DTMB provides technical guidance on how to securely wipe the devices. Questions about agency actions with mobile devices need to be addressed by the specific agency."

A spokesperson for MDEQ, which has rebranded itself the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy, pointed to the previous Snyder administration.

"The current administration [of Governor Gretchen Whitmer] is neither in a position to confirm the actions of, nor speculate on the motives of, employees and former employees that occurred six years ago," they said. The spokesperson declined further comment, citing the ongoing Flint criminal investigation.

Beyond the questions arising from the phone data, The Intercept uncovered more details behind multiple internal investigations Governor Snyder initiated into the Flint water crisis. One of the investigations — led by the Michigan State Police (MSP) to investigate MDEQ's culpability for the water crisis — was launched on the same day AG Schuette announced Flood as the Flint criminal investigation's special counsel in January 2016.

The other Snyder-launched investigation was led by the state inspector general/auditor general investigating MDHHS' role in the water crisis. In a sharply worded May 25, 2016 letter Schuette sent to Governor Snyder, the attorney general ridiculed the investigations, arguing that they "have compromised the ongoing criminal investigation" and "may effectively be an obstruction of justice."

After Schuette's letter demanding that Snyder cease his own Flint investigations, the governor announced a halt to them.

The Intercept obtained a draft of Schuette's letter from a week before it was sent to Snyder that indicates the final letter was softened compared to the draft shortly before it; the previous draft had indicated the attorney general believed Snyder's internal investigations weren't credible.

"The failure to halt your ongoing civil and administrative 'investigations' may cause the guilty to go free, obstruct justice, and result in gross injustice to the families of Flint and to the families of Michigan," the May 19, 2016, draft said.

"The AG wanted quotes around the word investigations in that paragraph; I don't know if he wanted that usage throughout," retired Judge William Whitbeck, a member of the Flint criminal investigation team, wrote to colleagues in a May 19, 2016 email obtained by The Intercept.

But in the final letter sent by Schuette to the governor on May 25, 2016, the quotation marks around investigations were removed. Another notable change from the draft letter was the removal of a section in which Schuette suggested that Lt. Lisa Rish, who led MSP's investigation into MDEQ's role in the water crisis, obtained "coerced statements" from MDEQ employees that the Supreme Court's Garrity v. New Jersey decision outlawed.

"Garrity issues of this type have the potential to complicate, and in fact have already complicated, our ability to conduct the type of thorough and timely criminal investigation that the Flint water crisis demands," the May 19, 2016, draft said. But in the final letter, mentions of the Garrity Supreme Court decision and "coerced statements" were removed.

Beyond the changes in the final letter sent to the governor, Snyder's top adviser and self-described "fixer," Richard Baird, was the point-person for Snyder who engineered the state police and inspector general/auditor general investigations, multiple sources familiar with the criminal investigation told The Intercept. With this knowledge in mind, Schuette copied Baird on the letter to the governor, along with Snyder's private attorney, chief legal counsel, and chief of staff.

In January, Baird was charged with obstruction of justice, misconduct in office, perjury, and extortion for his role in the Flint water crisis.

The attorney representing Baird did not respond to The Intercept's request for comment.

The state police investigation's report, obtained by The Intercept, minimized MDEQ's culpability in the water crisis. In the report, MSP Lt. Lisa Rish wrote that MDEQ employees she interviewed "denied any wrongdoing" and claimed they had followed federal drinking-water regulations while making decisions related to Flint's water. MSP interviewed 11 MDEQ officials, four of whom ended up being charged by AG Schuette as part of the Flint water criminal investigation.

In one example, Lt. Rish wrote that MDEQ supervisor Stephen Busch merely made a "misstatement" when he falsely told concerned EPA officials that Flint had an "optimized corrosion control program" in February 2015. As the Detroit Free Press reported, Flint "disastrously" had no corrosion control program in place at all, the lack of which resulted in lead leaching off of the city's older pipes into its drinking water.

Schuette did not respond to The Intercept's request for comment, nor did Lt. Rish or the Michigan State Police.

Snyder's internal investigations weren't the only red flags investigators discovered surrounding the governor and his top adviser, Baird.

The Intercept learned that departments, including MDEQ and MDHHS, were tasked with creating timelines for their respective actions during the water crisis. But like many other things inside the Snyder administration during the crisis, the timelines were routed through Baird, who was well-known in state government as Snyder's right-hand man and close friend dating back to when Baird gave the governor his first job out of college.

Baird's power as the governor's point-man even drew jokes of him being a "shadow governor."

Upon reviewing the timelines, Flood's investigators determined the state departments had omitted important facts and events, according to documents reviewed by The Intercept; more so, they learned the timelines were routed through Baird. Documents related to Flood's investigation accuse Baird of inserting false information into the timelines in order to provide state officials with an official story to tell if and when they were questioned over the water crisis.

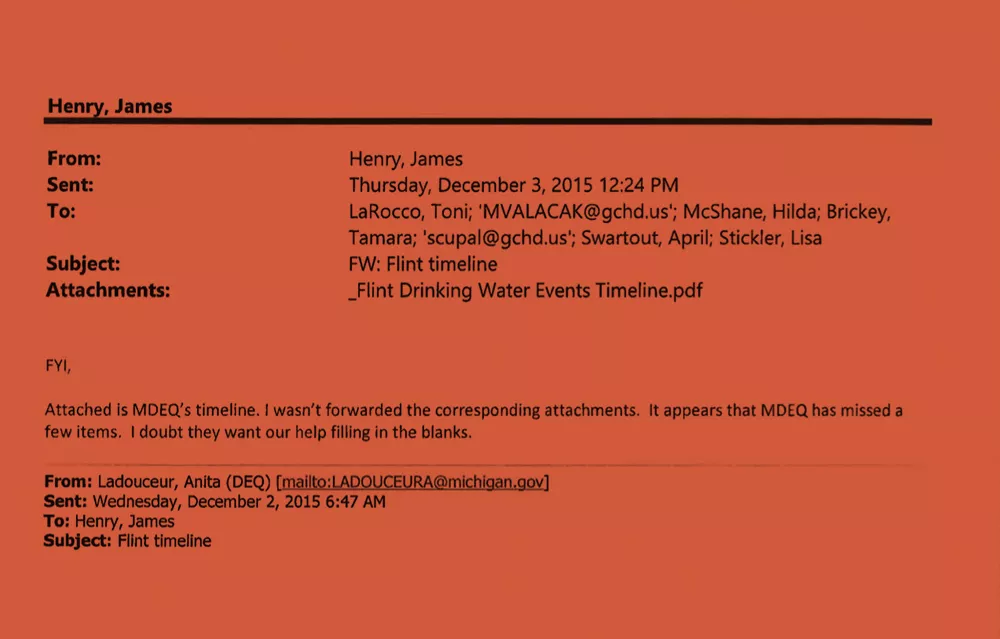

More than just allegedly false information, the timelines seemed to be missing important events linked to the water crisis.

"It appears that MDEQ has missed a few items," Henry, the Genesee County Health Department supervisor who sent prosecutors the tip about the "wiped clean" phones to investigators, wrote in a Dec. 3, 2015, email to colleagues that attached the Flint water timeline MDEQ put together.

"I doubt they want our help filling in the blanks," Henry wrote.

Soon after state departmental timelines were allegedly falsified, and around the same time that Snyder's questionable internal Flint water investigations were underway, Snyder administration officials voiced concern about pressure they were receiving to improperly withhold Flint water documents they felt should've been released to the public in response to a significant volume of FOIA requests, The Intercept has learned.

After releasing his own personal emails — which news outlets noted were largely unrelated to the water crisis and heavily redacted — Snyder told Congress that "relevant documents" from different state agencies would be released so that the public could have an "open, honest assessment" of what happened.

But some officials within his administration felt pressured to do exactly the opposite.

One week after Snyder's congressional testimony, Georgia Shuler — one of several DTMB analysts tasked with combing through Flint water emails to determine which ones should be released to the public in response to FOIA requests — emailed her supervisor expressing serious concerns about the process for releasing Flint documents, emails obtained by The Intercept show.

Shuler wrote her supervisor that during a meeting about the Flint water emails she and other analysts were tasked with going through to evaluate which emails should be released, the employee leading the meeting told Shuler and other analysts they "would not be held responsible if the documents ended up being missorted."

Shuler responded that she appreciated that, but a verbal assurance wouldn't provide her protection from any issues that may arise from improperly holding back relevant emails from public release.

"That's when I asked if I could have an email to that effect and she did not answer me and walked away," Shuler recounted to her supervisor, adding that one of the meeting attendees "replied to me that if your boss tells you to do something and you do it, you can't get in trouble for doing what you are told. The lawyer nodded but I replied that that was not always true and the meeting leader, lawyer, told me to stop talking."

Ultimately, Shuler said she was uncomfortable working on the FOIA project and asked to be excused, a request that was granted.

"If she determined an email was clearly not Flint-related — but it really was Flint-related — she wasn't going to be held responsible for that," an ex-DTMB official familiar with Shuler's concerns told The Intercept.

The process that determined which Snyder administration Flint water emails to release didn't stop at lower-level analysts like Shuler. After Shuler and other analysts conducted initial reviews of thousands of Flint emails, the trove of documents they determined should be released under FOIA then moved up the chain for a "Tier 2" review among department heads and communications staff, the ex-DTMB official, who was involved with the process, told The Intercept. Finally, the emails went to the governor's office for final approval, one current and one fomer DTMB official said.

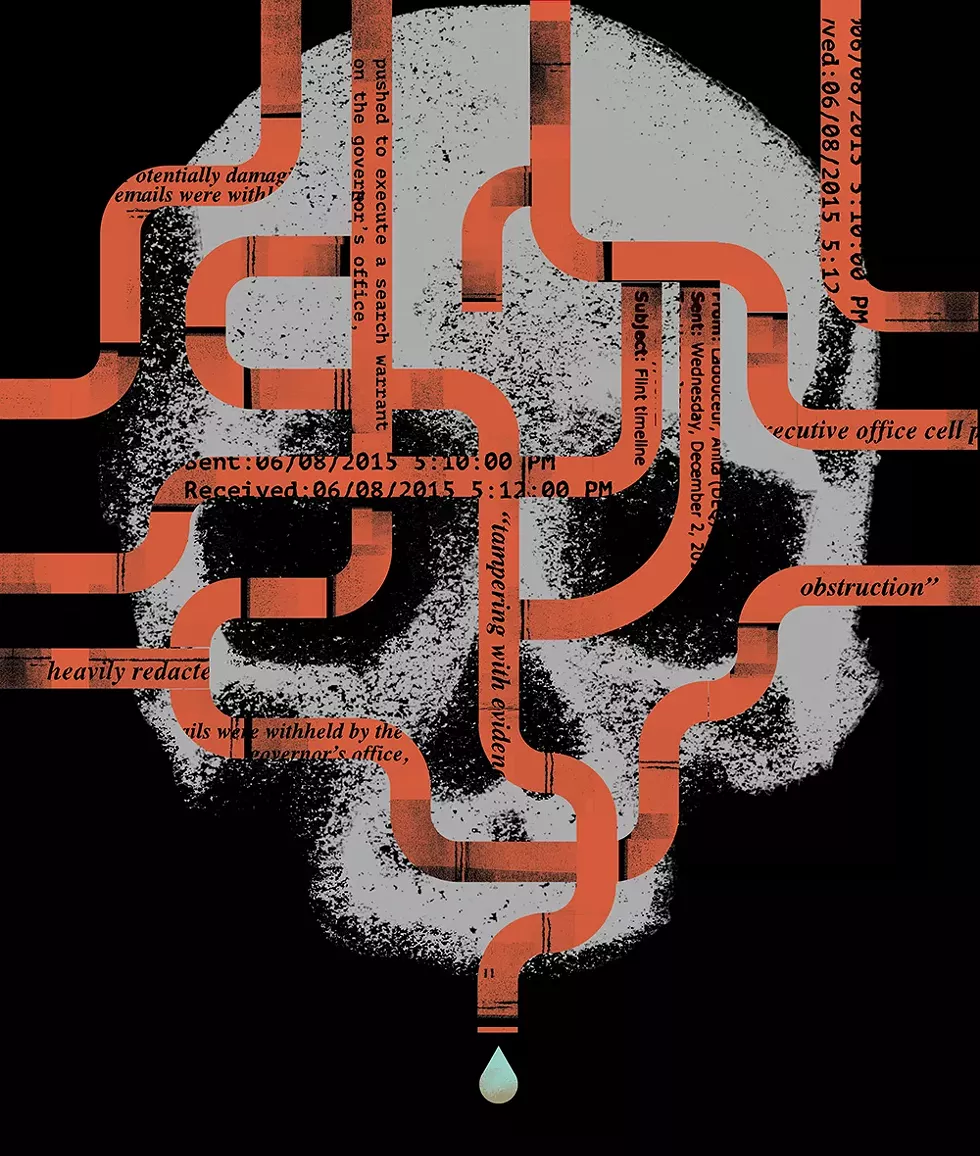

Potentially damaging emails were withheld by the governor's office, the former DTMB official alleged being told by then-DTMB chief of staff Jean Ingersoll. Ingersoll, the ex-DTMB official alleged, had told them that she attended a meeting in the governor's office where officials said that "they would never be handing over" some records. When the ex-DTMB official pushed back that the process seemed "shady," Ingersoll reiterated the marching orders from the governor's office and said "that's what we're going to do," the ex-DTMB official alleged.

Ingersoll, now with MDHHS, acknowledged to The Intercept that she sat in "one or two meetings" in the governor's office about Flint water emails, but said "I don't recall this conversation" about controversial documents being withheld from the public.

The alleged attempts to withhold Flint-related emails continued a Snyder administration trend of concealing communications. In 2013, Baird and other Snyder officials used their private emails to communicate about a secret, for-profit school model the Snyder administration planned on launching — ominously called "Skunk Works."

The move was par for the course for Baird, according to the ex-DTMB official, who alleged the governor's right-hand man once chided them for sending an email about Flint to his official Michigan government email.

"Don't ever email me there, always email me on my hotmail account," Baird allegedly told the ex-DTMB official on a call soon after the official emailed his government email, the former official alleged to The Intercept. "He never replied to the email; I think he was mad that I mentioned Flint in an email."

The alleged command by Baird was in sync with his overall aversion to leaving an official paper trail.

"Trust me amigo. Emails are fodder for our enemies' cannons," Baird wrote to ex-Flint emergency manager Darnell Earley in a March 13, 2015, text message obtained by The Intercept. "Suggest you default to the phone call or gotta minute? drop by approach...I learned this the hard way!"

“Trust me amigo. Emails are fodder for our enemies’ cannons,” Snyder’s right-hand man Richard Baird wrote to ex-Flint emergency manager Darnell Earley.

tweet this

A week later, Baird again texted Earley, who at that point had moved on from his role as Flint's emergency manager to become emergency manager for Detroit public schools.

"Sent u a note to the other email," Baird wrote, presumably referring to Earley's non-state government email. Earley responded, "on it." Earley didn't respond to The Intercept's request about whether Baird was emailing state business to his personal email about the Flint water crisis or any other issues.

Baird and other officials in the Snyder administration's use of private emails continued into the Flint water crisis. In December 2015, then-Snyder chief of staff Jarrod Agen scolded Baird and Meegan Holland, Snyder's communications director at the time, for using their private emails to discuss Flint water matters. In fact, Governor Snyder himself used private email to discuss Flint water matters, his then-spokesperson acknowledged at the same time the governor testified in front of Congress in 2016.

The Intercept learned of other internal Snyder administration turmoil during the water crisis among MDHHS officials who stewed over what they felt was the administration prioritizing its own political survival over the public health crisis in Flint.

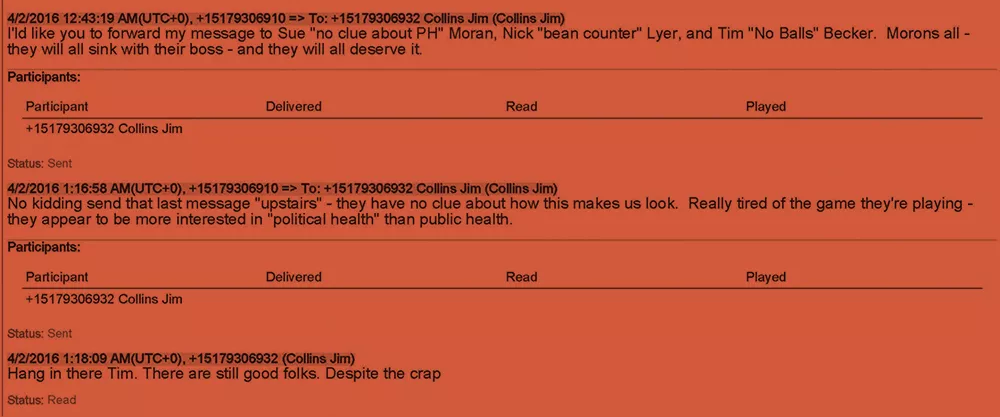

In an April 2, 2016, text message obtained by The Intercept, MDHHS epidemiologist Tim Bolen messaged Jim Collins, his boss and director of MDHHS's Communicable Disease Division. In the message, Bolen condemned MDHHS chief deputy director Becker and Sue Moran, deputy director of the Population Health Administration.

"Morons all, they will all sink with their boss — and they will all deserve it," Bolen wrote, seemingly referring to the MDHHS director Lyon. Soon after, Bolen texted Collins again: "No kidding send that last message 'upstairs' — they have no clue how this makes us look. Really tired of the games they're playing — they appear to be more interested in 'political health' than public health."

Collins responded: "Hang in there Tim. There are still good folks. Despite the crap." Neither Bolen nor Collins responded to The Intercept's request for comment.

As Flint prosecutors and investigators discovered the missing phone messages, Snyder's questionable internal investigations, and efforts by top officials to influence the testimony of subordinates, they were also waging a three-year, behind-the-scenes legal battle with Governor Snyder and his attorneys. On June 10, 2016, Snyder was served with an investigative subpoena, documents obtained by The Intercept show. The subpoena sought documents and communications that the governor and his top officials had about Flint's water dating back to when the governor entered office in 2011 through June 2016.

Soon after, Snyder's lawyer responded with 29 objections, documents obtained by The Intercept show, with Snyder's lawyer pointing to the heavily redacted 117,000 pages of "responsive documents" Snyder had already made public.

A few months later, in the fall of 2016, Snyder — with no court order in place that compelled him to provide the documents criminal investigators sought — continued to withhold the majority of documents and communications he was subpoenaed for months earlier, according to multiple sources familiar with the criminal investigation and documents obtained by The Intercept.

With Snyder and his attorneys stonewalling, special prosecutor Flood pushed to execute a search warrant on the governor's office, multiple sources familiar with the criminal investigation told The Intercept. But AG Schuette — a Republican who would go on to announce a run for governor to succeed the term-limited Snyder in 2017 — denied the request.

"Flood's hands were tied, Schuette said you cannot execute a search warrant on the governor," a source familiar with the matter told The Intercept, adding that Schuette said the criminal team had to route all requests for documents through Snyder's lawyer.

"They weren't giving things, they weren't honoring subpoenas," the source told The Intercept. Moreover, the documents that Snyder, and state departments under him, were providing to investigators were missing crucial metadata, multiple sources told The Intercept, including the full length and sequence of email chains, which state officials were copied and blind copied on emails, and who the emails might have been forwarded to.

It's the "document's DNA," a source told The Intercept. Essentially, Snyder was sending "screenshots of emails" to prosecutors. Flood did not respond to The Intercept's request for comment.

Flood moved to compel Snyder to comply with the original subpoena for documents in the fall of 2016, documents obtained by The Intercept show. Soon after, Flood withdrew the motion based on a "stipulated agreement" with the governor's attorney; the agreement mandated that Snyder would begin producing the documents he was subpoenaed months earlier for on Oct. 14, 2016. From there, the agreement said, the governor would continue producing documents "on a rolling basis approximately every two weeks from the date of its first production."

But still with no court order in place to force the governor to comply, he and his attorneys didn't honor the agreement, multiple sources told The Intercept, continuing to slow-walk the criminal investigation.

Around the same time in October 2016, criminal prosecutors were tipped off that top officials in Snyder's administration, including Baird, had approached other state officials before their interviews with criminal prosecutors in order to influence their testimony, according to documents obtained by The Intercept and sources familiar with the matter.

"It's come to my attention as recent as yesterday that some of the witnesses that we have been bringing in have been contacted by government or former government employees to talk about testimony that they may or may not give," Flood told MDHHS' Jay Fiedler in a confidential interview in October 2016 obtained by The Intercept. (Fiedler responded that no one had approached him to influence his testimony.)

While interviewing Wurfel, Snyder's press secretary, Flood also noted improper attempts by state officials to influence the testimony of other Snyder administration officials.

"There have been times where people have been contacted, after testimony that have sat in investigative subpoenas before, to talk about what they testified to," Flood told Wurfel. "There have been — as disclosures have shown, people have been talked to in cases where witnesses have been talked to about what they should say in an Investigative Subpoena...if someone were to do that, I would consider it tampering with evidence and an obstruction, and I would charge anybody that would do that to you."

In the January 2021 indictment against Baird for perjury, extortion, misconduct in office, and obstruction of justice, prosecutors referenced Baird's attempt "to influence/interfere with ongoing legal proceedings arising from the Flint water crisis."

Prosecutors' behind-the-scenes legal battle with the governor continued into 2017. As a result, Flood filed a second motion to compel Snyder to comply with the original 2016 subpoena. In a "Brief in Support of The People of The State of Michigan's Second Motion to Compel Governor Rick Snyder's Compliance With Investigative Subpoena," obtained by The Intercept, Flood wrote that the governor was "now simply refusing to comply with significant requirements of the Subpoena."

Documents that Snyder had provided prosecutors were "patently noncompliant with the requirements of the subpoena," Flood wrote, adding that the governor's lawyer had "arbitrarily decided not to search for" large numbers of documents prosecutors had asked for. He argued that Snyder had "custody or effective control over massive amounts of information that is relevant to an ongoing investigation."

Some of the relevant documents Snyder was withholding, Flood wrote, included "MDEQ Governor Briefings, Governor daily briefings, Executive Staff meetings, and Flint Water Crisis-related conference calls, updates, and reports" that were all "in the custody or effective control of the Governor."

Snyder and his lawyers were particularly obstinate about not providing prosecutors with the governor's daily briefings from the summer and fall of 2014, multiple sources familiar with the criminal investigation told The Intercept. Considering Snyder's health and environmental departments were already communicating about Flint's Legionella outbreak in October 2014, access to the governor's daily briefings would allow investigators to see if Snyder had received notice of the deadly outbreak during this time — nearly a year and a half earlier than the January 2016 period Snyder testified to Congress that he became aware.

As The Intercept previously reported, investigators found potential evidence that Snyder was notified much earlier: meeting notes from an Oct. 22, 2014, MDEQ managers meeting that included the blurb "Governor's Briefings'' with a corresponding mention of the Legionella outbreak in Flint. The memo, which came two weeks before Snyder's reelection, seemed like a smoking gun — written notice to the governor 16 months earlier than he claimed to have learned about the outbreak. As The Intercept also reported, investigators had other reasons to believe the governor knew about Legionnaires in Flint as early as October 2014 after finding a suspicious, two-day blitz of phone calls between Snyder, his chief of staff, and MDHHS' director in October 2014; calls that investigators concluded amounted to the trio working to prevent news of the outbreak from going public.

But prosecutors were not able to obtain Snyder's actual briefings from that time; instead, the governor provided investigators with daily briefings from less pertinent periods that were also heavily redacted, a source familiar with the matter told The Intercept. One such briefing provided to investigators, obtained by The Intercept, was from April 2013, a year before the Flint River switch, with most of the briefings unrelated to the topic of Flint's water and heavily redacted.

Snyder "picked the most sanitized ones and redacted everything on every page almost," the source said.

In Flood's motion, he also made mention of "executive office cell phones that were not timely imaged or forensically preserved" — highlighted by Lieutenant Governor Brian Calley, whose cell phone wasn't forensically preserved until January of 2017, according to Flood.

Calley didn't respond to The Intercept's request for comment.

Flood explained that he had relied on the "good-faith representations" from the governor's attorney that Snyder's subpoena response would be completed by "January or February of 2017," but that "it became clear by May of 2017 that the Governor had no intention of complying with significant requirements of the subpoena."

On top of that, the documents Snyder had given to prosecutors were fraught with technical issues, including "duplication issues, blank/withheld documents, missing custodians, unidentified custodians, and inconsistent and questionable redactions," Flood wrote.

Furthermore, Flood stated that the governor's attorney hadn't produced any privilege logs, lists lawyers provide prosecutors with for each document they are withholding and the justification for doing so. But the special prosecutor had not received "a single privilege log reflecting thousands of otherwise responsive documents being withheld by the Governor," he wrote in the motion.

By the end of 2018 — two years after Snyder was originally subpoenaed for Flint water documents — Flood petitioned a judge to allow any future motions he would file to compel the governor to be made public. Snyder's lawyers objected, lobbying to keep review of all contested documents confidential, known in law as "in-camera review."

In the motion, Flood revealed that Snyder's lawyer had stated he was now considering "whether the Governor would assert his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination as a basis in refusing to fully respond to the subpoena."

Among other things, Flood wrote, he had evidence of "data stores and devices from key executive officials under the effective or actual control of the Governor that were not searched; relevant documents and data that were not preserved despite having notice of the OSC's criminal investigation; and missing material information that was required to be produced."

It would be "a travesty of justice" if Snyder were able to continue to not cooperate with the subpoena, Flood concluded.

Soon after the 2019 discovery of 23 boxes in the basement of a state building containing Flint water documents, hard drives, and cell phones, AG Nessel fired Flood as special prosecutor in April 2019. Solicitor General Fadwa Hammoud, who was appointed by Nessel to replace Flood as the top Flint water prosecutor, claimed that under Flood legal discovery "was not fully and properly pursued from the onset of this investigation."

Along with Flood, Nessel fired Andy Arena, the investigation's chief investigator, and the majority of the criminal team responsible for charging 15 state and city officials with crimes over the Flint water crisis over a three-year investigation. In June 2019, prosecutors with Nessel's revamped Flint water investigation issued search warrants to seize the cell phone Governor Snyder used while in office, along with other mobile devices belonging to him. With the seizure of Snyder's devices, prosecutors seized devices connected to dozens of members of his administration. Soon after, prosecutors dropped the remaining charges against eight state and city officials — including MDHHS director Lyon, Michigan's chief medical executive Wells, and two of Snyder's Flint emergency managers— citing flaws in the original three-year investigation and that "all evidence was not pursued."

A year and a half later, in January 2021, Nessel's prosecutors charged Governor Snyder with two counts of willful neglect of duty, a misdemeanor charge, for "willfully neglecting his mandatory legal duties under the Michigan constitution and the emergency management act, thereby failing to protect the health and safety of Flint's residents."

Eight other state and city officials, including Baird, Snyder's former chief of staff Jarrod Agen, and two ex-Flint emergency managers appointed by Snyder, were faced with a slew of felony and misdemeanor charges related to the water crisis.

In March, a judge granted Snyder's lawyers a several-month hold on the criminal case against him to allow Snyder's defense time to go through what they claim to be 21 million documents.

In April, the Flint water crisis entered its seventh year. After two investigations spanning different attorneys general, no state of Michigan or city of Flint official has faced a jury or been convicted. Beyond the search for justice, residents and activists on the ground have passionately challenged claims, often reported by the national media, that their water is safe to drink, telling The Intercept that residents are still experiencing rashes and receiving often odorous and discolored water.

"Since 2014, Flint residents have been posting photos and videos of rashes, discolored water, health questions and concerns about high water bills," Melissa Mays, a Flint resident and activist, told The Intercept. "For seven years we have been consistently dismissed and ignored. We are halfway through 2021 and we are still getting our water through corroded pipes and fixtures but somehow those in charge have decided to tell the world everything is fine, but common sense tells us that our water STILL flowing through damaged and contaminated infrastructure means that our water is STILL not fixed."

Peter Hammer, a Wayne State University law professor who produced a definitive report on the Flint water crisis that identified structural racism as its root cause, expressed serious concerns about Snyder's evading prosecutors' requests for years, as well as wiped phones belonging to state officials.

"If true, this is a disturbing pattern that goes far beyond the problems of having inadequate state laws requiring disclosure of public records," Hammer told The Intercept. "All citizens have an obligation to comply with criminal processes; this is substantially more true for public officials. There can be no accountability without transparency."

Hammer added that if he had the details The Intercept is revealing at his disposal from the very beginning of his analysis of the water crisis, his conclusion would have "shifted towards intentional forms of misconduct and criminal behavior."

On whether Snyder was involved in efforts to cover up the Flint water crisis, Hammer was blunt.

"If the actions reported here are accurate, it is impossible for me to believe that the governor was not aware of the efforts to hide and destroy damaging information."

A version of this story was also published by The Intercept. It is republished with permission.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit.