Inside the grassroots fight to end gerrymandering in Michigan

Toying with our elections

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Thanksgiving 2016 was not an easy one in America. The holiday fell just weeks after Donald Trump's upset presidential win in an especially contentious, dramatic election, and the divide in American politics was represented at plenty of the nation's Thanksgiving tables.

Katie Fahey was one of those not looking forward to that year's dinner. Her family holds Trump, Bernie Sanders, and Hillary Clinton supporters, and there seemed to be little common ground among them.

Many of those who supported the Trump and Sanders campaigns weren't otherwise politically active, and that got Fahey thinking about how to keep her family engaged in politics, but on an issue on which everyone can agree.

What came to mind is one that is a problem for Republicans, Democrats, and independents across the country — gerrymandering. Put in simple terms, gerrymandering is the undemocratic process of politicians drawing legislative districts' lines in a way that ensures that their party wins more districts and the other party loses. It's politicians picking who votes for them, not people picking the politicians. The motivation for gerrymandering legislative districts is simple — the party that controls the most legislative districts writes the laws. And Michigan is one of the country's most gerrymandered states.

As we'll explain later, gerrymandering is one reason unpopular laws like "rape insurance" were approved in Michigan, and the process is related to the number of shady and extreme politicians representing the state.

Around that time, Fahey put up a Facebook post announcing her intent to figure out a solution to gerrymandering. It included a simple, "If you want to help, let me know, smiley face," Fahey tells Metro Times. She got a big response, with people asking, "Hey, OK, what are we doing about it?"

Nearly two years later, the 29-year-old Fahey — who has no prior experience in politics or political organizing — is heading up the drive to solve partisan gerrymandering in Michigan through a redistricting amendment to the state's constitution.

In late 2016 she launched the nonpartisan, nonprofit group, Voters Not Politicians, which grew out of that Facebook post into an organization with more than 5,000 volunteers. VNP successfully collected over 400,000 signatures to get redistricting reform on the Nov. 6 ballot, successfully took on a big business-backed legal challenge, and has already knocked on 125,000 doors as it campaigns for the passage of what's now known as Proposal 2.

Put in simple terms, gerrymandering is the undemocratic process of politicians drawing legislative districts’ lines in a way that ensures that their party wins.

tweet this

If approved, the proposal would establish an independent redistricting commission that would put people instead of politicians in charge of drawing the state's political districts. The commission would be composed of four Democrats, four Republicans, and five independents, the latter of who would who have no affiliation to the state parties or politicians.

Fahey's success with VNP thus far is the perfect example of grassroots organizing. Though she admits Thanksgiving dinner still wasn't exactly fun, her family is behind her on the effort, and her mom alone collected 700 signatures.

"They're all supportive, which is really nice, and it's helped us gain a better understanding of each other. And no one wants corruption or government that isn't representing voters," she says.

Fahey adds that as the discussion has grown, "It's been refreshing to be focused on something positive and not have the conversation dictated by political parties, but to have the conversation dictated by voters in Michigan."

Gerrymandering, explained

It's not hard to spot a gerrymandered district on a map, because it usually resembles some bizarre shape. The word comes from Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry, who signed a bill in 1812 to redraw the state senate districts to benefit his Democratic-Republican Party over the rival Federalist Party. A Boston Gazette cartoon seized upon the fact that one of the districts looked like a dragon-like, mythological salamander.

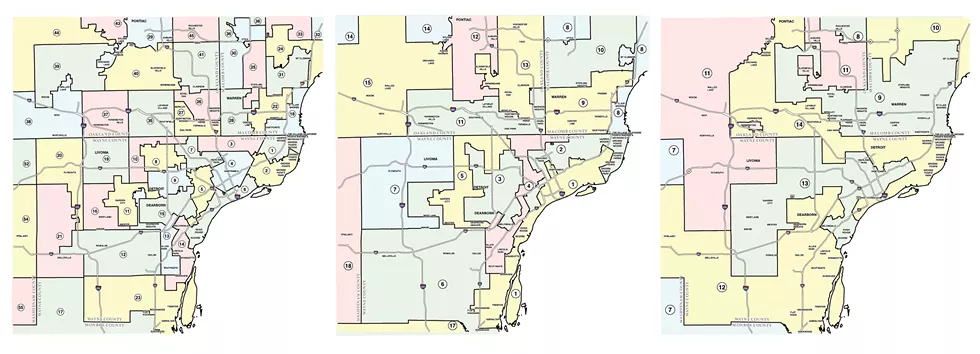

The process of gerrymandering districts starts with the political party that's in power in the census year, which occurs every 10 years. That party's politicians draws the legislative districts in a process called redistricting. In Michigan, the lines were redrawn by Republicans in 2010.

Gerrymandering is the political art of "stacking" one party's voters into as few districts as possible, and "cracking" another party's voters across as many districts as possible. Keeping all of one party's voters in few districts is a great way to ensure they don't win many districts, and, therefore, don't get to write the laws.

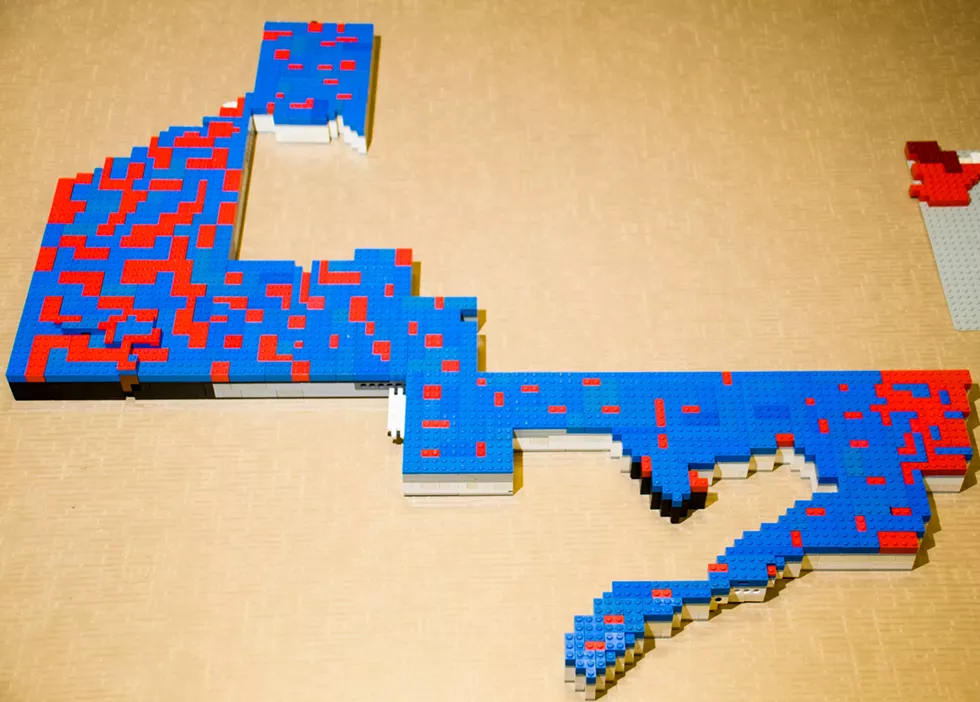

That's "weaponizing" redistricting, says Wayne State University associate political science professor Kevin Deegan-Krause. He travels the state giving presentations on how gerrymandering works, and uses Lego blocks to provide a very useful visual aid.

In a hypothetical model, Deegan-Krause imagines a small Lego world with 49 voters — 24 are represented by green Lego squares, and 25 are yellow. The goal is to draw seven districts.

"The question I always ask when I have audiences is if you're playing this game and you have no stake in it, no dogs in the fight, then how do you want to draw it?" he says. "And the answer they usually give is you draw lines across, or down — you draw normal squares that human beings can recognize, and usually if you do it that way you get three greens and four yellows, or four greens and three yellows."

But again, that's if you're not trying to win the game. What if you were trying to rig the game? The answer, Deegan-Krause says, is counterintuitive.

"The first thing you do if you're green is give the yellows a district all by themselves," he says. "That seems really weird — why would you as a green give them a district? But the answer becomes really clear. We can create six other districts that have four greens and three yellows. I can create six districts that have a slight green majority, so even though they are in the minority they now have a supermajority of seats."

Yellow can do the same thing to green — it can carve out an all-green district and then split the yellows. The disparity "has nothing to do with what people think or people moving out — it only has to do with how we draw the lines," he says.

"This is a really huge problem, and it has become worse over time," Deegan-Krause says, noting that political parties now use sophisticated data science and computer programs to figure out where voters live, right down to an individual house, and what cars they drive to what magazines they subscribe to.

"[Politicians and lobbyists] can do this with almost surgical precision," he adds. "They can start to draw lines in and around particular houses, particular neighborhoods, so [whoever is drawing the lines] can almost always win this game."

For his next example, Deegan-Krause lugs out a Lego model that's so large and unwieldy he has to reinforce it with special hardware. It's a model of Michigan's 14th Congressional District, represented by Democrat Brenda Lawrence, and a solid example of gerrymandering.

"Our joke was if you can't build it out of Legos, it shouldn't be a district," Deegan-Krause says. "If it falls apart when you pick it up... that should be the new Supreme Court standard."

In 2010, Republican lawmakers packed predominantly Democratic African-American voters into one space, which snakes from downriver and through Detroit to the Grosse Pointes, Oak Park, Farmington Hills, Southfield, and Keego Harbor all the way up to Pontiac — forming a massive zig-zag shape that is almost entirely divorced from any recognizable geographical or municipal boundaries, save for the natural curve of the Detroit River and the hard border of Eight Mile Road. A small, Tetris-like puzzle piece is missing from the mass — that's Farmington, which was carved out for its Republican voters, now part of Republican Dave Trott's 11th district.

"Imagine you are trying to represent this district," Deegan-Krause says. "I spoke to one poor staffer from this district and she said she spends half her days on the road getting from one place in the district to another. One person has a different congressional district than the person living across the street, and a different one is halfway down the block."

(Gerrymandering is such an abstract concept that it demands such novel visual aids. In a recent video for NowThis, Fahey jogged down a street in Grand Rapids that contained only about 10 residential homes but was represented by three State House districts; it took her only 46 seconds to jog through all three.)

But gerrymandering is not only a Republican trick: "This is something Democrats do when they're in charge. This is something Republicans do when they're in charge," Deegan-Krause says.

In Michigan, Democrats gerrymandered the state's districts in the 1970s and 1980s. And around the nation, Dems have gerrymandered states like Illinois and Maryland into their favor. Republicans are even asking the U.S. Supreme Court to find Maryland's districts unconstitutional.

The raw vote numbers from the previous two elections confirm the issue here. In 2014, Michigan voters cast 30,000 more ballots for Democrats than Republicans in the state's House of Representatives races. Despite that, Republicans hold a huge advantage of 63-47 there. As for the state Senate races, the raw count came in close to even but Republicans held a 27-11 majority.

The same thing occurred in that year's U.S. Congressional districts. Democratic candidates received 50,000 more votes in 2014, but Republicans sent nine representatives to Washington, D.C. while Dems sent five.

A similar scenario played out in 2016. According to numbers posted on the Michigan Secretary of State's website, Republicans won the raw vote count for the Michigan House of Representatives by about 3,000 votes. Still, the party holds a 63-47 majority.

'Dem garbage'

Despite what's obvious, politicians from both parties deny that they gerrymander. Those who oppose redistricting reform also claim that drawing lines is part of a legislator's job description.

"That's one of the elements of a representative democracy. The legislature gets to legislate, not some ad hoc group that has no voter accountability," Republican strategist Bob LaBrant told Metro Times for our 2015 cover story on gerrymandering.

But what LaBrant didn't mention at the time is that he and other Republicans in 2011 very deliberately set out to gerrymander districts to give Republicans an unfair advantage. Emails released as part of a federal lawsuit over gerrymandering show how LaBrant worked to help secure a safe district for Dave Camp, a former Midland congressman who has since retired.

"We will accommodate whatever Dave wants in his district," wrote LaBrant on May 18, 2011, to two Republican consultants and a Camp staffer, according to emails obtained by Bridge Magazine. "We've spent a lot of time providing options to ensure we have a solid 9-5 delegation in 2012 and beyond."

Emails reveal that another Republican aide said a Macomb County district is shaped like "it's giving the finger to (Democratic U.S. Rep.) Sandy Levin. I love it." Another email from a GOP staffer allegedly bragged about cramming "Dem garbage" into four southeast Michigan congressional districts.

These are the type of political games of which voters in both parties across the nation seem to finally be tiring. In May in Ohio, voters approved a redistricting proposal by a roughly 75-25 margin. In California, voters in 2008 approved a similar measure, and its legislature's approval rating went from 9 percent to 40 percent in one year. An independent commission set up in Arizona has also largely been considered a success.

The only polling so far on the Michigan proposal shows a high number of undecided voters. The Glengariff Group found 38 percent of those it polled supported the amendment, 31 percent opposed, and about one-third are undecided.

Fahey says VNP's internal polling is better, and she adds that there's a silver lining in the high number of undecideds because people who learn about gerrymandering and redistricting reform tend to agree that an independent commission, and stripping power from politicians and lobbyists, is a good idea.

"We ask, 'Do you think politicians work for you, or someone else?'" she says. Not many think the latter.

The issue is also getting a lot more publicity nationally. That's partly because Democrats in some states and Republicans in Maryland have asked the U.S. Supreme Court to consider extreme gerrymanders in their respective states. In Michigan, media attention and the efforts of VNP and the League of Women Voters is making the public more aware, says Sue Smith, redistricting director for the League.

"A lot more people do understand the problem we have in Michigan and the need for redistricting reform, but there's still a ways to go on educating people," she says. "More people are realizing that it's not a good situation when politicians are choosing the voters, and it should be the other way around."

'Rape insurance' and other unpopular laws

The link between gerrymandered districts and unpopular laws isn't direct, but it's clearly there. In short, it's tough to vote out lawmakers who pass unpopular laws when all the independents or opposition party's voters are packed into few districts. That insulates politicians from voter anger, and Michigan saw its legislature pass some notable pieces of unpopular legislation.

The Michigan legislature's approval rating is at about 15 percent, yet there's little change.

"The way we see people in Michigan are voting doesn't line up with our representation in Lansing and Washington," Fahey says, adding that the state is split just about 50-50 between the two parties and is known as a swing state, yet Republicans hold a supermajority in the State Senate.

That's partly how Michigan got the "Religious Freedom Restoration Act" even though two-thirds of residents disapproved of it. The law allows religious adoption agencies that receive taxpayer money to deny an adoption to same-sex couples, or anyone else seeking to adopt who doesn't subscribe to Christianity. Some polling indicated 70 percent wanted same-sex couples' civil rights expanded.

In 2012, a poll found more than 70 percent opposed a proposed law that would allow concealed firearms in the state's schools. The Republican legislature shrugged at the vast opposition and sent the bill to Gov. Rick Snyder. He vetoed it, partly on the grounds that a majority of voters opposed the idea. The Senate approved a new version of the bill in November 2017 — just after a gun-related massacre at a Baptist church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, that left 26 people dead and 20 more injured — but the House never took up the new bill.

Over a clear majority of residents' objections, Republicans also pressed forward with the wildly unpopular and controversial "rape insurance." Most of the same legislators have also pushed for more charter schools while providing them with taxpayer money. That's despite that polls found 84 percent of respondents agreed that Michigan needs tougher laws governing charter schools, and 73 percent of respondents supported a moratorium on new schools until those laws are passed.

In 2014, polls found widespread support for increasing the minimum wage to $10.10 an hour. Republicans initially blocked that effort but, under intense public pressure, agreed to increase the minimum wage to $9.20 in 2017. However, that wasn't enough for some residents. Last year and earlier this year, a nonpartisan group pushed a ballot proposal to raise the minimum wage to $12 per hour. Despite support for the idea, Republicans passed a law to raise the minimum wage to $12 an hour in March 2019. But it's likely that they will kill the bill in lame duck in December.

Perhaps the most blatant example of defying residents' wishes occurred in 2012 when Michiganders voted to repeal the unpopular emergency manager legislation. The law allowed the state to strip locally elected governments of their power, and residents were uncomfortable with that. Republicans didn't care, drafted a new version of the law, and rammed it through a month later, attaching it to appropriations and making it referendum-proof.

"When you know that people in Michigan are giving very clear orders and you ignore them, then you probably feel more beholden to special interests than your constituents," Fahey says. "But if you have guaranteed election results, then you're not afraid of being voted out of office."

In a healthy democracy, voters would push out politicians and the party that passes a succession of unpopular laws. And in Michigan, voters tried to do so when they cast more ballots for Dems in 2014. It didn't matter — most of those votes went to a small number of Democratic candidates, and Republicans not only remain in power, but maintain supermajority in the Senate and a wide majority in the House.

Crazy politicians

Gerrymandering is also partly behind what would appear to be an increase in the number of dysfunctional politicians. If a district is drawn dramatically in one party's favor, there's no real opposition, and voters are more forgiving of a candidate's flaws if he or she is on their own team.

That means the winning candidate is most likely going to be decided in the August primary, when some candidates will adopt more extreme positions to play to the base. Extreme positions in one party could mean providing a single-payer health care system or tuition-free college. Extreme ideas on the other side could include concepts like ethnic cleansing and Holocaust-denying.

"When extreme candidates get elected in primaries — because they are extreme — a lot of times, those are the voters who don't want their candidate to compromise," Fahey says. "They want an extreme right or extremely left candidate, so it erodes the amount of moderates in Michigan."

Among Michigan's crop of unstable or extreme candidates are former Reps. Todd Courser and Cindy Gamrat, who likely wouldn't have lasted long had they faced any serious competition. Their careers exploded in a spectacular fashion when they were caught using taxpayer money to cover up an affair; Courser then cooked up a fake gay sex scandal in an unsuccessful attempt at a distraction.

Former Grand Rapids-area Tea Party Rep. Dave Agema traded in racial politics before Trump made it mainstream. He served between 2007 and 2013 and earned his reputation by quoting KKK leaders on his social media accounts. Republicans in 2008 booted Agema from the House Appropriations Committee after he chose to take a trip to Siberia to hunt snow sheep during the state's budget crisis — yet he survived his re-election bids.

Gary Glenn, a Midland Tea Party Republican, is cut from the same cloth. He's president of the American Family Association of Michigan, a conservative religious organization that the Southern Poverty Law Center labels a hate group.

And unchecked lunacy is bipartisan. Democratic State Rep. Brian Banks won just under 70 percent of the vote in 2014 while facing sexual harassment charges for allegedly forcing a male staffer to perform a sexual act on him.

Sen. Virgil Smith, also a Democrat representing Detroit, held onto his seat while facing felony charges for shooting at his wife, and didn't let go until 2015 when he went to jail for 10 months.

An independent commission could help reduce the number of questionable candidates who make it to Lansing by creating more competitive districts. If there's more competition, candidates will have to present ideas, an appearance, and a rap sheet that is acceptable to more than just their party's base.

The independent commission

How can we be sure that the commission will function as advertised? Fahey says she believes VNP developed a sound solution. The proposed constitutional amendment would create a commission of 13 registered voters — four each of Republicans and Democrats, and five who self-identify as independents — who are randomly selected by the Michigan Secretary of State.

The law would prohibit officeholders, candidates, their employees, certain relatives, and lobbyists from serving. New "strict" redistricting criteria would require "geographically compact" and contiguous districts of equal population, which reflect Michigan's "diverse population and communities of interest." Importantly, the districts would not provide "disproportionate advantage to political parties or candidates."

A simple majority of commissioners can approve a map, but at least two Dems, two Republicans, and two independents must agree on it. In theory, that will force compromise. If there is no majority, then commissioners will submit proposed maps, and the commission will use a ranking system to select the map. If that fails, a final map will be randomly selected from the maps submitted by the commissioner.

When applying, applicants who wish to serve on the commission would be required to identify which party they belong to. The two major state parties will have a limited number of strikes available to block applicants from participating.

‘More people are realizing that it’s not a good situation when politicians are choosing the voters, and it should be the other way around.’

tweet this

Commissioners are also chosen using a random selection process, so "the odds of an applicant who lies about their party affiliation being selected is remote," VNP states on its site. Parties can also use their limited strike as a safeguard against anyone who comes off as suspicious. Names and applications will be public, so anyone can look into an applicant and their past activities or background.

Right now, politicians and lobbyists draw maps behind closed doors with no public input. The independent commission's process would be public and the commission "must publish everything used to draw the maps, including the data and computer software used."

Fahey notes that the legislation is long — about 14 pages. But that's partly because the law was carefully crafted with every conceivable attack that politicians might use to wrest power back from the people.

"These 13 people will have a more honest and interesting discussion than any of the rest of us have because they have to sit in a room with someone from the other side and in the end, nothing happens unless they agree," Deegan-Krause says. "They're not saying everyone will act in the public interest and not the self-interest. They're taking the self-interest into account, but it has to be balanced so your self-interest has to be balanced against mine, which is very much like a Founding Fathers thing to do."

While the proposal might not get 100 percent approval, it would be a vast improvement over the current system. It's also the type of solution for which Fahey has long been looking. She first considered the redistricting issue in school, long before Thanksgiving 2016 and the Facebook post that helped VNP grow legs. A professor in one of her college classes taught a lesson on gerrymandering, and Fahey remembers asking her why no one fixed the problem.

"She said that it's always been done this way, and I have a distinct memory of being upset and thinking, 'Well, I don't like that answer.'"

If you don't like that answer either, you can vote yes on Proposal 2.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.