Illegal document purge in Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office blocks freedom for the wrongfully convicted

In Michigan, prosecutors are required to retain the files of defendants serving life sentences for at least 50 years or until the inmate dies — or face a maximum penalty of two years in prison

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

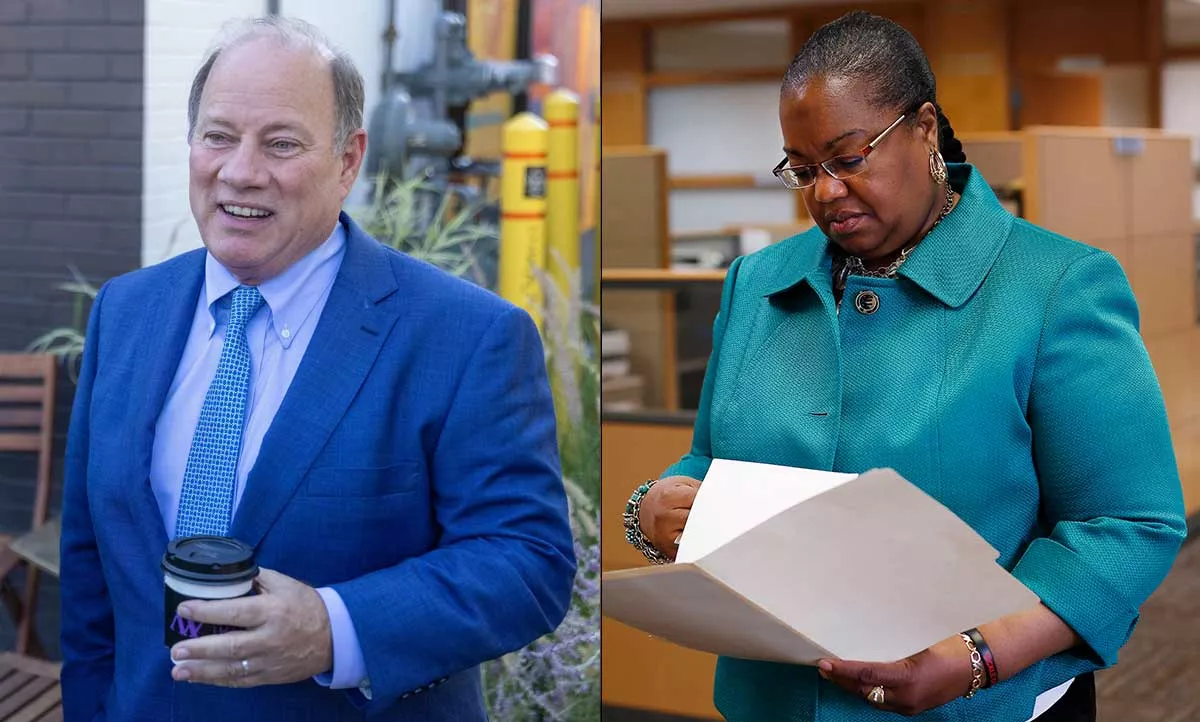

Wayne County illegally destroyed troves of criminal files allegedly when Mayor Mike Duggan was the elected prosecutor, creating a staggering obstacle for wrongfully convicted inmates seeking to prove their innocence, Metro Times has learned.

Between 2001 and 2004, while Duggan was prosecutor, most if not all misdemeanor and felony records from 1995 and earlier were allegedly removed from an off-site warehouse and destroyed in violation of state law.

In Michigan, prosecutors are required to retain the files of defendants serving life sentences for at least 50 years or until the inmate dies. Violating the law carries a maximum penalty of two years in prison.

The records contained a wealth of vital information, including police and forensic reports, lab results, transcripts, video recordings, and witness statements, all of which are essential for mounting a defense against wrongful convictions.

The file purge was not previously reported. Metro Times learned about it recently in interviews for an ongoing series about wrongful convictions.

What makes the file purge especially concerning is that it involved records from a deeply troubling era in Detroit’s Homicide Division, a time plagued by rampant misconduct, false confessions, constitutional abuses of witnesses and suspects, and a widespread federal investigation. In the 1980s and 1990s, the misconduct among police, especially homicide detectives, was so pervasive and egregious that the U.S. Department of Justice demanded reforms to avoid a costly lawsuit while Duggan was the county prosecutor.

The two decades of misconduct produced an alarming number of wrongful convictions and false confessions, as illustrated by a spike in exonerations and court settlements stemming from that era. However, legal experts say many more innocent people are still behind bars, but the destruction of the prosecutor’s records has compromised the integrity of countless convictions, leaving some inmates without a viable path to freedom.

The purge has also impeded the work of Wayne County Prosecutor Kym Worthy’s Conviction Integrity Unit, which she created in 2018 to investigate claims of wrongful imprisonment.

Prosecutor points finger at mayor

How the records came to be destroyed remains somewhat of a mystery, but there are indications of a coverup. A county logbook that registers the destruction of public records appears to have been tampered with, which would also be a crime.

“There is a logbook that had sections that recorded the numbers of purged files,” the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office said in a statement to Metro Times. “The record book had the pages 1995 and older removed from the book. We don’t know how that occurred.”

Worthy, who replaced Duggan as prosecutor in 2004, is pointing the finger at Duggan’s administration. During Duggan’s tenure as prosecutor, employees for his office “were enlisted to locate and purge the files that were on site and located in the off-site storage,” ostensibly to make room for newer records, according to the current prosecutor’s office.

While Duggan was prosecutor, his staff warned “that purging felony files was extremely ill advised,” according to Worthy’s office.

When Worthy became prosecutor in July 2004, she said she was notified of the purge and was “astounded.”

“One of the first issues I had to deal with was the concern that under my predecessor’s administration all files were ordered destroyed that were pre-1995,” Worthy told Metro Times. “I must have had at least 20 people report this to me. It was very well known throughout the office. I was astounded that this even included homicide files! I could not believe it and even to this day, we cannot locate files pre 1995.”

Worthy added, “This has caused massive problems for us, especially for our Appellate Division and now our Conviction Integrity Unit.”

In statements to Metro Times, Duggan, who has been mayor since 2014, repeatedly denied involvement in the destruction of files and claimed he had no idea there was even a purge, even though prosecutors routinely rely on those records for appeals, post-trial motions, public records requests, and other routine tasks.

Some of the destroyed records would have been less than a decade old.

Asked why she didn’t publicly reveal the file purge when she first took office, Worthy declined to comment.

If the files were purged during his administration, Duggan suggested, it could have been done without his knowledge by the Wayne County Building Department, which he said exclusively “managed and controlled” the documents at an off-site warehouse.

“When Prosecutors wanted older files, they filled out a request form and the files were retrieved by the records management staff of the Buildings Department,” Duggan’s spokesman John Roach tells Metro Times. “The Prosecutor’s Office otherwise had no access to, or responsibility for, the management or storage of those files.”

Worthy’s office took issue with that characterization and said prosecutors are ultimately responsible for safeguarding the files.

“WCPO had custody, management, and control over the files stored in the warehouse,” according to the statement from the prosecutor’s office. “When assistant prosecutors needed old files it was common for them to search the on-site files and also to go to the actual warehouse with the person who was the administrator of the files to physically search for the files themselves. WCPO’s appellate unit had a vested interest in keeping the files because they were routinely needed to respond to post-trial motions and appeals in state and federal court.”

Wayne County Executive Warren Evans’s Office, which runs the Building Department, told Metro Times it would look into the claims by Duggan and Worthy but didn’t respond by deadline.

In a follow-up statement last week, Duggan stood by his contention that he was unaware of the purge and said there’s no credible evidence that he was involved.

“It is inconceivable that any member of the prosecutor’s office would ever have condoned any destruction of documents in violation of the Michigan Records Retention Act,” Roach said. “If there is a claim that the prosecutor’s staff at some point approved an improper purging, name the staff involved, the date they are claiming it was done, and the process they followed. Absent that, it is impossible to respond to vague memories of unidentified people making claims about actions of unnamed staff more than 20 years ago.”

It isn’t the only time records vanished in a Duggan administration. In October 2019, the Detroit Office of the Inspector General (OIG) said top officials in Duggan’s administration ordered the deletion of emails related to the nonprofit Make Your Date, which was run by the mayor’s now-wife. Duggan’s administration dodged charges after Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel said in April 2021 that the “facts and evidence in this case simply did not substantiate criminal activity.”

In September 2020, Duggan and the city won the annual Golden Padlock Award, which recognizes the most secretive U.S. agency or individual every year, for the intentional destruction of emails.

The immeasurable impact

Whatever the case, the impact of the file purge is far-reaching and profound. Tens of thousands of people, some of them juveniles, have been convicted of felony crimes in Wayne County since the 1980s, when a rise in homicides coincided with alarming reports of widespread police misconduct. Investigations and lawsuits uncovered staggering corruption — from framing suspects and withholding exculpatory evidence to rounding up witnesses and suspects for long periods without a warrant. Over the past two decades, lawsuits filed against the city and its police department for wrongful convictions have cost taxpayers tens of millions of dollars.

It was a bad time to be accused of a crime, and the police tactics led to a rise in false confessions and exonerations.

Steve Crane, a private investigator who works on behalf of prisoners who maintain their innocence, says the purge is inexcusable and detrimental to countless prisoners.

“Wayne County not only failed to protect the public records from destruction, they intentionally destroyed the records, knowing the records contained evidence involving a person’s life imprisonment,” says Crane, who has helped win the release of three wrongfully convicted inmates.

Without the prosecutor’s files, Crane worries that innocent people are going to remain behind bars.

“They might spend the rest of their lives in prison because of this,” Crane says. “The last guy we got out, we had prosecutor files. These files are crucial to understanding whether a person is innocent or not.”

Fighting for freedom

For inmates like Carl Hubbard, the loss of those files has been devastating. He was convicted of fatally shooting 19-year-old Rodnell Penn in a violence-prone area of Detroit’s east side in 1992, largely based on the prosecution’s key witness, 19-year-old Curtis Collins. On the first day of his trial, Collins recanted and said he incriminated Hubbard because police threatened to jail him for murder and other crimes if he didn’t testify against Hubbard.

Collins was thrown in jail for two days for perjury, and on the third day of the trial, he returned to the stand and changed his story, saying he saw Hubbard shoot Penn.

At the age of 28, Hubbard was sentenced to life in prison in September 1992 without any physical evidence tying him to the shooting. He has been fighting for his freedom since and has compiled evidence that he’s innocent: Collins recanted again in a sworn affidavit and said he wasn’t anywhere near the murder scene. Other people signed affidavits saying they saw Collins at another location that night. And a witness to the shooting said he saw someone else pull the trigger.

The owners of a nearby store, where Collins initially said he saw Hubbard moments before the shooting, said Collins was not in their business that night. They were familiar with Collins because he was banned from the store for previous behavior.

Hubbard believes he can prove Collins was lying during his testimony, which would be significant because the case hinged on his account. Collins testified that he left the area in a taxi cab after witnessing the shooting.

Through police records, Hubbard discovered the authorities subpoenaed the cab company to determine if Collins had, in fact, been picked up. But findings from the subpoena were never turned over to his lawyer, Hubbard says, which would constitute a Brady violation, giving him grounds for a new trial. Brady violations occur when prosecutors fail to disclose evidence that could benefit the defense.

Late last year, Hubbard enlisted a private investigator, Chris VanCompernolle, to retrieve the prosecutor’s files to find out what the subpoena uncovered. But to his dismay, the prosecutor’s office said in a letter in November that the file could not be found.

“I was hurt,” Hubbard recalls in an interview from Macomb Correctional Facility. “It was a harsh reality, like I was going to die in prison. There was no justice going to be served. I could no longer prove my innocence.”

Hubbard has been in prison for 32 years, and he’s only seen his daughter once. He has never met his grandson. In January, his mother died.

“I just want the truth to come out,” Hubbard says. “It’s all I ever wanted.”

VanCompernolle says the significance of the purged records cannot be overstated.

“This is a big deal because Carl could spend the rest of his life in prison if he can’t get this information,” VanCompernolle tells Metro Times.

Innocence denied

Attorneys advocating for wrongfully imprisoned clients say the loss of the prosecutor files has created significant challenges. The Michigan Innocence Project, which won the release of 42 falsely convicted people since it was founded at the University of Michigan in 2009, has been unable to acquire Wayne County prosecutor files for dozens of prisoners because the records were destroyed.

“We’ve had dozens of cases impacted by this,” David A. Moran, co-founder of the Michigan Innocence Clinic, tells Metro Times. “You don’t know what is in them that could help. It’s a serious problem.”

Without the files, Moran says attorneys try to get as much information as they can from courts, police, and previous defense counsel. But they’ll never know what they’ve missed in the prosecutor’s files, Moran says.

Worthy’s Conviction Integrity Unit, which is tasked with freeing innocent inmates, is also encountering setbacks. Since the unit was created in 2018, 38 inmates have been either exonerated or their cases have been dismissed. But the CIU is facing a staffing shortage, and the lack of prosecutor records has posed a significant challenge.

The CIU has received more than 2,300 requests to review cases since it was created. Of those, the unit has examined a little more than half so far.

Without the prosecutor’s files, the task is even more daunting and is detracting from other cases, according to the prosecutor’s office.

“It should be acknowledged that it takes time to reconstruct files that could be spent doing other work,” the office said in its statement.

Valerie Newman, the CIU director, says that her team has been able to find some documents using other avenues, but overall the file purge has made the unit’s work more difficult and time-consuming.

Mack Tiggart, who has been in prison since 1989 for a first-degree murder conviction, will never forget when he found out the prosecutor’s files in his case were destroyed. He’d believed he was closer to proving he was innocent and just needed the prosecutor’s file.

Then in May 2015, he received a letter from the prosecutor’s office, saying the county’s previous version of the CIU “was unable to obtain sufficient materials to make a complete evaluation of your case,” and without the prosecutor files, “no further action … will occur at this time.”

“I almost had a heart attack,” he recalls in an interview from Muskegon Correctional Facility. “It hurt my mother. She was so upset. It took two or three years for her just to come around. She said Kym Worthy promised my mother and my family that they would pull my files and reexamine them.”

Tiggart had reasons to be optimistic. In court filings, two firearm experts discredited the ballistic evidence.

“The examiner’s testimony fell far short of what is scientifically reliable in the field of ballistics technology,” Tiggart’s attorney Roberto Guzman said in a letter to Worthy in September 2013. “His opinion was garbage, particularly since no laboratory analysis was done on the confiscated evidence to support that opinion.”

Police also lost evidence. The contested ballistic analysis went missing, and the prosecutor’s records had been destroyed, making it virtually impossible for Tiggart to prove his gun was not used in the murder, despite expert witnesses saying it almost certainly wasn’t.

One of the primary reasons Tiggart’s records are so important is because Michigan State Police exposed an alarming amount of botched ballistic testing at Detroit’s crime lab. The lab was forced to close in 2008, and Worthy’s office pledged to reexamine numerous cases after an MSP audit of 200 cases found that 10% of the ballistic test results were erroneous.

In cases that were botched, the prosecutor’s files could contain evidence that shows erroneous data was used for a conviction, defense attorneys say.

In June 2005, Tiggart’s co-defendant Cornelius Stanley was dying and swore in an affidavit that he had “framed” Tiggart because police had “coerced” him and threatened to charge his sister with murder if he didn’t implicate Tiggart.

“I shot Eric Wheeler and framed Mack Tiggart to protect myself, my sister and her two children,” Stanley wrote. “But now I am at death’s door. I am afraid to face GOD knowing that lies condemn Mack Tiggart to life in jail and he and my sister did nothing but help me when I was down on my luck.”

During a 2009 city council meeting, Worthy said she planned to reexamine many of the cases built on ballistic testing and assured one of Tiggart’s daughters that prosecutors would review his case.

Tiggart, who is now 68, has been waiting ever since.

On Memorial Day in 2022, Tiggart’s first daughter, Amanda, died from a massive seizure at the age of 44. Three months later, he says his mother died from a “broken heart.”

Before she died, Tiggart says his mother told him, “Don’t ever stop fighting for your freedom. The day will come when God will send the right person to help you get out of there. Mama have to go and lay down next to Amanda.”

Mark Craighead, who was exonerated of murder in 2022 and has been an advocate for innocent prisoners since then, says the illegal destruction of records shines a brighter light on the systematic suppression of evidence that contributed to wrongful convictions.

“They destroyed these records so you can’t fight them,” Craighead tells Metro Times.” If you have the cards stacked up against you like that, there’s no way you can win your freedom. This shows that there’s corruption from the top to the bottom — from the mayor to the prosecutor’s office, judges, and police department.”

More than wrongful convictions

The impact of the destroyed files goes beyond the wrongfully convicted. Prosecutors rely on archived records to glean insight into long-running criminal enterprises, to weigh in on prisoners’ requests for parole, and to file sentencing motions on convicted felons who have committed new crimes.

When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2016 that mandatory life sentences for children were unconstitutional, the files were used by defendants and prosecutors during resentencing hearings.

Those files could become paramount again for people convicted at young ages. The Michigan Supreme Court is considering whether to extend its ban on automatic life sentences for 18-year-olds to include 19- and 20-year-olds.

“In those cases, we still have to look at the circumstances of the offense, the evidence, and the victims have to be contacted,” says Rachel Wolfe, a defense attorney for prisoners who claim they are innocent. “There is so much important information in those files.”

Prosecutor files are also used by inmates requesting gubernatorial pardons or commutations. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer commuted the sentences of 35 inmates and granted four pardons since becoming governor in 2019. Since 1969, Michigan governors have commuted the sentences of 379 prisoners, including 162 who were convicted of first-degree murder, according to the Michigan Department of Corrections.

Additional files missing

Records from 1995 and earlier aren’t the only ones missing. Metro Times interviewed four prisoners whose files were never found for convictions between 1997 and 2003.

In 2003, when Duggan was prosecutor, Michon Houston was convicted of first-degree murder for the fatal shooting of Carlton Thomas on Detroit’s west side. The conviction was based on the testimonies of two witnesses, but their accounts differed. One of the witnesses, Jovan Antonio Johnson, later recanted, claiming he had been threatened by both the police and the real killer, Lavero Crooks, known on the streets as “Country.” The second witness was Crooks himself.

In a 2013 affidavit, Johnson said his testimony was false, explaining that Crooks had threatened him into implicating Houston. He also claimed that Crooks orchestrated his arrest in a drug deal shortly after the murder to pressure him into naming Houston as the shooter. Johnson said detectives further coerced him by threatening to charge him with murder if he didn’t comply.

In 2014, another witness, Tony Miller, came forward with a sworn affidavit, stating he was “completely sure” that Crooks was the shooter, as he had witnessed the crime. However, no one had ever interviewed him about what he saw. Additional testimony in 2021 from another person described Crooks as “wild and violent” and noted that it was common knowledge in the neighborhood that “Country” was responsible for the murder.

Houston and Crooks had clashed before the killing. According to the 2021 affidavit, Houston believed Crooks’s violent behavior was bringing unnecessary police attention to the neighborhood. Despite these developments, Houston’s attempts to prove his innocence have been hampered by missing records.

In 2020, Houston sought to obtain his police and prosecutor records but was told they couldn’t be found. The CIU informed him that the recanted testimony alone was insufficient to overturn his conviction without the records.

Houston, now 44, remains in prison, asking, “How can I prove my innocence without those files?”

Eugene McKinney is a 54-year-old Detroiter who has been in prison since he was convicted of arson and first-degree murder in 1997.

McKinney claims he was falsely convicted and that police coerced witnesses to incriminate him in exchange for leniency. He says he had ineffective counsel and that prosecutors violated his constitutional rights by denying him a probable cause hearing.

But prosecutors have lost his records.

“Without that file, there’s no evidence that a probable cause hearing was held, even though I know one wasn’t held,” McKinney tells Metro Times. “The prosecutor’s file is really important to me, and I need to get it. Where do I turn to?”

He added, “There were other witnesses that came forward that said someone else did it. I’m entitled to a new trial because of new evidence from the police department because there was a witness who said the suspects weren’t me.”

Despite the promising evidence, McKinney feels stuck without the prosecutor’s file. He says someone needs to be held accountable.

“They need to be prosecuted because they are withholding some important evidence that could exonerate me,” McKinney says.

Since Worthy became prosecutor, she says she has made it a priority to preserve and safeguard homicide records and “ultimately convinced the county to provide us space to efficiently store files” at a building in Livonia. She says she would never destroy “a homicide file or a violent felony or capital case.”

Her office is also working on a project to digitize records to make them more accessible.

Worthy says she knows the importance of retaining the files. In her final six years as an assistant prosecutor, she focused almost entirely on homicide trials.

“The way I put together cases and trial files were my bread and butter,” Worthy said. “After a case was over, our trial files were to be forever preserved. These files were sacrosanct and trial prosecutors were always concerned when they turned them in that they be kept.”