Meet the crazies

While a rogue miscreant will sometimes manage to cloak their identity enough to slip through an election, the cast and show in Michigan's legislature is something entirely different.

Gerrymandered districts open a route to Lansing for the parties' extremists, crazy people, criminals, or plain dumb. If a district is drawn dramatically in one party's favor, there's no opposition to stop a shady or stupid candidate. Thus, Michigan's legislature now holds a higher percentage of questionable politicians than anytime in memory, Brewer says.

"Gerrymandering tends to make the Legislature a more extreme body with public policy consequence that we have seen," he says.

Consider the well-documented misadventures of Courser and Gamrat, who are costing taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars. A secret recording made by a Courser staffer revealed he plotted a bizarre plan to send out a fake email accusing himself of sleeping with a male prostitute and doing drugs. That would prevent the revelation of his real wrongdoing — an affair with Gamrat. In the email, Courser labeled Gamrat "a tramp, a lie, and a laugh" complicit in his behavior.

The email, Courser told the staffer, would be a "controlled burn" to "inoculate the herd" in an apparent reference to voters.

Of course, that didn't go as intended. Instead it became fuel, and eventually the legislature moved to jettison Courser and Gamrat for using public funds to cover up their affair.

Prior to the ongoing Courser-Gamrat show, Agema repeatedly grabbed the headlines. He served in the legislature between 2007 and 2013, representing the Grand Rapids area, and earned his reputation by popping white power literature onto his social media accounts.

Perhaps his most infamous post came on New Year's Eve 2014, after he was out of office, though it still speaks volumes about who represents Michigan. In it, Agema quoted a KKK leader arguing that black people "cannot reason as well. They cannot communicate as well. They cannot control their impulses as well. They are a threat to all who cross their paths, black and non-black alike."

So maybe he was a skilled politician? Not really. Notably, the legislature booted him from the House Appropriations Committee after he chose to take a trip to Siberia to hunt snow sheep during the state's 2008 budget crisis.

Unfortunately, Agema isn't the only hatemonger in the capital. Gary Glenn, a Midland tea party Republican, recently issued "agenda alerts" on social media to "warn" the public that the news editor at the Midland Daily News is gay. Glenn is president of the American Family Association of Michigan, a conservative religious organization that opposes what it calls the "homosexual agenda" and is classified as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

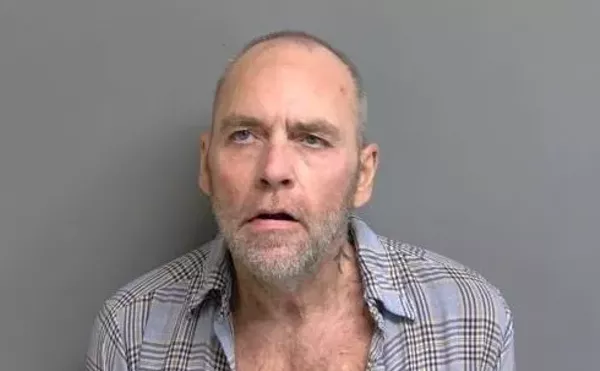

It sounds bad, and it is, but some of those representing districts "stacked and packed" with Democrats aren't much better. Rep. Brian Banks, whose district covers parts of Detroit, Harper Woods, and Grosse Pointe Shores, is an eight-time felon convicted of credit card fraud and passing bad checks. He won just under 70 percent of the vote while facing sexual harassment charges for allegedly forcing a male staffer to perform a sexual act on him.

Sen. Virgil Smith, 35, also a Democrat representing Detroit, is facing four felony charges for allegedly assaulting and shooting at his ex-wife in May.

Jack Lessenberry, a political analyst for Michigan Public Radio and an MT columnist, says the gerrymandered districts have "poisoned" the political process in Michigan, and he offered a harsh take on those fringe characters that have made it to the Capitol.

"This is the way people in insane asylums act," Lessenberry says. "Most of these people ought to be on some kind of medication and strapped down. The results are they are destroying our state ... and effectively destroying any chance of anything getting done."

Hot-button topics

No two issues are as emotional and as seemingly impossible to resolve quite like gun control and Michigan's crumbling roads.

However, as with gay marriage, the emergency financial law, or rape insurance, polls indicate solutions that a large majority could live with but that lawmakers continue to ignore.

While the gun control discussion is complex, most seem to agree that having more guns in schools is a bad idea. Proposed legislation to allow concealed firearms in schools isn't totally straightforward because open carry is already permitted. But the message from most voters polled in 2012 on concealed firearms in schools was very clear: "We're entirely sure we don't want concealed guns in our schools' halls."

But that fell on deaf ears in the Legislature, and Republicans eventually knocked out a new law that permitted concealed guns in schools, though Snyder ended that with a veto.

Now, three years later, several public school districts have declared their schools "gun-free zones." The moves were in line with the vast majority of their communities' views, supported by every superintendent in the state but one, and were upheld in court, so far. However the same Republican lawmakers are rushing through a new law that would eliminate the "gun-free zones" by allowing concealed weapons in schools. They claim they're doing kids a "favor" because the law would also eliminate open carry.

And that's a direct consequence and perfect example of gerrymandered districts producing a legislature that ignores Michigan residents, Brewer says.

"A more moderate, reasonable legislature would listen to the education community on this issue," he says. "An overwhelming majority of voters said, 'Let us take on these issues based on educational policy,' and almost all said, 'We don't want concealed weapons in our schools.' This is an extremist legislature that thinks it knows better than the education professionals in our state."

Similarly, the legislature seems intent on ignoring polling data found on roads. Surveys conducted immediately after voters rejected Proposal 1 in May found 64 percent support for raising the sales tax from six percent to seven percent if all new revenue went to roads and transportation. It also found more than 85 percent oppose funding road repairs by making cuts to K-12 school funding or health care for the poor and elderly. The poll also found that 76 percent of voters are against cuts to revenue sharing for municipalities and 63 percent oppose cuts to higher education. All polls show opposition to a gas tax increase.

Despite that, the latest Republican-approved proposal includes a gas tax increase and "cannibalizing" $600 million out of the budget to fix the roads. It's hard to imagine a scenario where $600 million comes out of the budget and doesn't impact cities, education, or health care — typically Democratic priorities.

John Lindstrom, publisher of Gongwer News Service, an independent news agency covering Lansing, says the discussion's direction is the result of one-party control.

"Republicans have made it very plain they want to put together a proposal that doesn't need Democrats' votes," he says. "That's the situation you get when you have a legislative House so overwhelmingly tilted toward one party or another. What happens with the roads affects everybody, so it would be logical to have both parties involved with a resolution. But Republicans are in a situation where they don't need to do that."

Redrawing the lines

A 2012 EPIC/MRA poll shows a majority favor redistricting reform, and Bernie Porn, a pollster with the agency, suspects that's still the case. Especially as the legislature's approval rating hangs around 15 percent and the tea party's support continues to erode.

But he adds that it's not that simple because gerrymandering is "an issue people do not understand a whole heckuva lot." So much so that the only poll EPIC/MRA ever scuttled dealt with redistricting reform concepts. Porn says, "People just did not really understand what it was all about."

But redistricting reform is the antidote and those pushing for the cause mostly agree the answer is establishing a nonpartisan redistricting commission to draw legislative districts. As of now, only six states have such commissions in place, but more are considering them after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled earlier this year that they are constitutional.

How one would look in Michigan is unclear, though those on the Democratic side want politicians out of the process altogether. In Arizona, a five-person commission with two Republicans, two Democrats, and one independent draws the lines. A 15-person commission redrew the lines in California in 2011, though the new map faced, and survived, three legal challenges.

Smith, of the League of Women Voters, notes that neither party's base is particularly happy in either state, "and that's a good thing," she says, adding that an independent commission should keep politicians from drawing their own districts.

But Bob LaBrant, a Republican strategist with the Sterling Corp., says legislators should remain a part of the process. He's concerned the commissions in California and Arizona, for example, establish districts based on "communities of interest." What can constitute a community is too loosely defined, LaBrant says.

He favors an alternative used in Iowa, where the legislative services bureau develops proposed districts, and the legislature votes to approve or reject the map.

LaBrant says he just isn't comfortable taking politicians totally out of the equation.

"That's one of the elements of a representative democracy. The legislature gets to legislate, not some ad hoc group that has no voter accountability," he says.

The first step toward any new approach is to shed some light on the issue, an effort the League of WOmen Voters is undertaking by holding 25 town hall meetings this fall to discuss redistricting. Ultimately, they would seek a constitutional amendment allowing for the establishment of a nonpartisan commission, and getting that on the ballot would require around 400,000 signatures and $1.5 million, Smith says.

Lessenberry adds that the support and commitment from a well-connected activist who can fund, organize, and inject energy into such a campaign is needed.

So far, no one is stepping forward, though he said someone like former Republican Rep. Joe Schwarz, or Jocelyn Benson, the dean of the Wayne State University Law School, could handle the job.

Regardless of how change looks, it's not clear as to whether the districts could be redrawn before 2020. But without meaningful redistricting reform, it's "more of the same," Lessenberry says.

Voters will still be ignored, and the state will continue to be a playground for deranged politicians and far right extremists. Even if residents find themselves fed up enough to really try to do something about it, the goons in Lansing, secure in their jobs, will shrug and continue building a state fewer and fewer feel good about.

"Until this changes we're never going to get anywhere," Lessenberry says. "The elections don't matter, and we're just going to interchange groups of dysfunctional people as the state continues to fall apart."