How Michigan tried to discredit Flint pediatrician's lead warnings

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Courtesy photo

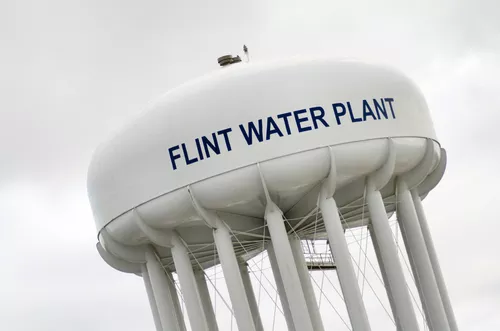

In the following months, Hanna-Attisha investigated and discovered that children were indeed being poisoned by lead in the water. She found the percentage of children with lead in their bloodstream increased after the water switch, while nationally the number of children with lead in their blood was decreasing. Legionnaires disease and pneumonia deaths also increased during that time.

Realizing the situation's urgency, Hanna-Attisha publicly shared that data at a hospital press conference. Despite the clear and hard evidence, state officials tried to discredit Hanna-Attisha. She also learned around that time that at least one other state agency was covering up the spike in lead poisoning. As she tried to sound the alarm, she encountered "roadblocks at every direction."

Hanna-Attisha recounted those issues in a Monday interview with Fresh Air's Terry Gross. She was on the show to discuss her new book, What The Eyes Don't See, which details how her discovery and the state's response played out.

"The state said that I was an unfortunate researcher, that I was causing near-hysteria, that I was splicing and dicing numbers," Hanna-Attisha told Gross. "It's very difficult when you are presenting science and facts and numbers to have the state say that you are wrong."

"There was so much denial in the Flint story, so much information was hidden from those who tried to get the information," she continued. "I wish I had known at the time that I was looking into it that the health department at the state level had looked into children's lead levels, and on their own had already seen a spike in lead levels. I wish that was out there and shared ... because then the crisis wouldn't have gone on for as long as it did."

Gross then asks, "So some authorities knew and did nothing?"

"Absolutely and that's why we have so many criminal charges," Hanna-Attisha responds.

Gross also notes how the switching the city's water source from the Great Lakes to the Flint River was a cost-cutting measure that, ironically, continues to cost taxpayers tens of millions of dollars.

But that's nothing compared to the lifelong issues with which the victims of the poisoning have to contend. There is no safe level of lead exposure, and there is no "cure" for lead poisoning.

"The consequence of lead exposure is something we don't see ... it drops the IQ of a population of children," Hanna-Attisha said. "It impacts behavior and increases the likelihood of things like ADD, impulsivity, violence, criminality, lead exposure — it has lifelong consequences that you don't see right away."

You can listen to the full interview on Fresh Air here.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.