Controversial tech

Though Craig boasted the department had become more data-driven under his watch, a reliance on controversial tools and strategies without concrete evidence that their benefits outweighed the costs would emerge as a recurring theme.

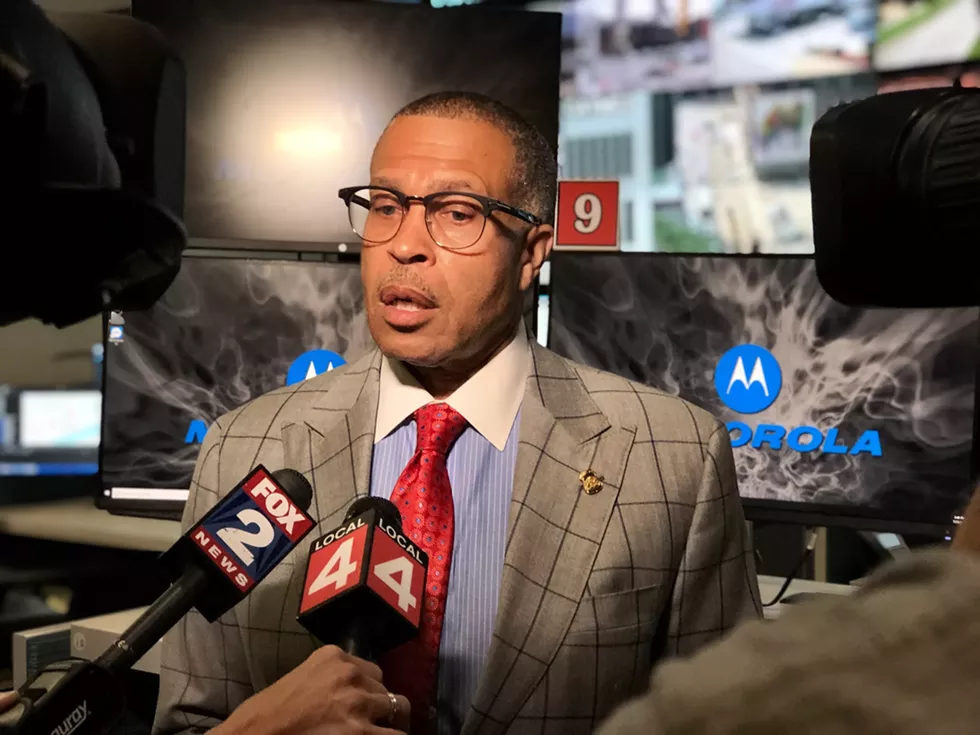

Nowhere is this more evident than the department’s Real Time Crime Center — a futuristic, windowless room inside Detroit Public Safety Headquarters where computer monitors and big screens beam high-definition footage from a vast, citywide surveillance camera network. Opened in 2017, it’s the nerve center for Project Green Light and its complementing facial-recognition technology, which allows officers to quickly cross-reference suspect images with a database containing tens of millions of mug shots, driver’s license, social media, and other photos.

As Craig’s DPD quietly phased out Operation Restore Order, it pivoted to these technologies to boost productivity in the face of a stubborn personnel shortage driven by higher pay and safer conditions offered by departments in the suburbs. But both proved controversial: Project Green Light for its unproven benefits and potential for civil rights abuses, and facial recognition for resulting in the wrongful arrests of at least two Black men who are now suing the department.

Though the department contends the tools “assist” in dozens of investigations each year, how many cases they’ve actually helped solve is unknown, as it nor the prosecutor’s office appear to keep track of the number that result in charges.

Still, Craig has doubled down on both, undeterred. Last September, he won council approval to extend the department’s facial recognition technology contract, misleadingly promising that a new policy would prevent future problems even though he’d previously insisted its safeguards were already in place. And he continued to encourage businesses to take on the approximately $5,000 and monthly costs to join Project Green Light, repeatedly citing dubious evidence he claims shows it’s responsible for crime reductions, particularly a 40-percent decline in the rate of carjackings since 2016.

The messaging appears to have been effective. Project Green Light continues to grow, and residents' faith in the camera network is so strong that some have staged demonstrations to push businesses to join. Business owners, meanwhile, have said they risk losing customers without the perceived security.

“The Duggan and Craig PR machine has been meticulous in tapping into the worst fears … of people who’ve been disinvested in and are looking for some semblance of hope,” Tawana Petty, a Detroiter and national organizing director for Data for Black Lives, said of mass surveillance in the city. “But it’s not safety they’re providing it’s the perception that they’re pursuing the goal of safety, which is all they need to stay in power.”

Policing, of course, requires trying different approaches. But it should rely on sound analysis and take into account adverse consequences, said Jannetta, the Urban Institute researcher.

“It’s fine to be experimental, but you want to be somewhat rigorous about where you draw your ideas from and test them on the other side,” he said. “When crime goes down, [public officials] can say everything can be successful — it’s definitely common, but I wouldn’t say it’s kosher.”

Overall, Craig’s track record on crime reduction is mixed and follows trends observed in other major cities, department data shows. Over the eight years he ran the department, property crime dropped in line with reductions seen in the half-decade before he took the helm, then plummeted in 2020, ending 47 percent below 2013. Violent crime, meanwhile, generally fell under his watch — albeit more slowly than the five years prior — before a 2020 surge that pushed the rate 2 percent higher than 2013.

But for Hall, Craig’s former deputy who left in 2017 to run the Dallas Police Department, chiefs cannot be held solely responsible for reducing crime.

“Craig did exactly what he was supposed to do and the technology did exactly what it was supposed to do and that is reduce crime as much as it can,” she said. “There is all types of data that shows that crime has a direct correlation to poverty, and until city and other officials realize they’re going to have to put more resources [into] education and jobs, that is only when you will see a drastic impact.

“[If] we’re looking for police departments to eliminate crime, we’ll be waiting for the second coming of Jesus.”

Residents, generally, don’t appear to fault Craig either.

“People have become desensitized to the crime — they’ve become immune,” said John Bennett, a retired department veteran and lifelong Detroiter. “It’s been tough for so long that any positive morsel — we hang onto that and become apologetic for the people in leadership.”

But for Bennett, Craig “had one job” — fighting crime — “and he didn’t do it. And when you think of the fact he’s running for governor, what are you running on, what is your record?”

Summer 2020

Just as Rodney King created an opening for Craig to distinguish himself 30 years ago, George Floyd was effectively his springboard into the political realm in Michigan, sparking a wave of Black Lives Matter demonstrations he rode to his current status as a Republican gubernatorial frontrunner.

Last summer, as Craig condemned Floyd’s killing as murder to a majority-Black and Democratic audience in Detroit, he was introducing himself to a new one: white Republicans who watch Fox News. Through increasingly frequent appearances on the cable network, Craig became known as the man who “kept Detroit from burning” because his department “did not retreat” — the implication being that officers’ aggressive tactics prevented the looting and arson seen in other major cities.

It is true that Detroit did not see much damage and that Craig’s department used tactics later struck down in court in the few instances in which police and protesters clashed — like tear gas, rubber bullets, and riot sticks against demonstrators who had merely ignored dispersal orders.

But there’s disagreement as to whether Detroit was ever really at risk of serious unrest — its painful scars from 1967 still evident and the overwhelming majority of near-nightly demonstrations led by largely peaceful activist group Detroit Will Breathe — and whether the department’s hardline approach helped suppress turmoil.

To the extent violence was possible, longtime community leaders credit themselves with acting as a buffer to prevent it by joining the then-chief in discouraging Detroiters from participating in the events. Pastor Mo Hardwick, a longtime community leader who supported Craig during the demonstrations, insists that if police “went too hard” and confronted more Detroiters, “it would have lit the match” for a riot. Craig, for his part, is moreso credited locally for transparency than aggression, like his swift release of video from a deadly police shooting that sparked a melee last July. A rumor had spread that victim Hakim Littleton was unarmed, but the video showed he shot at officers first.

Craig has stood by the aggressive tactics, arguing that his officers were under threat from rocks and other projectiles. But the injuries were lopsided; far more demonstrators were hurt than officers, according to previous accounts from both sides, and where officer injuries were minor, demonstrators suffered broken ribs and an open-head fracture, among other things.

Much of the police response has not survived a legal challenge: Demonstrators won a temporary court order curbing the department’s use of violent crowd-control tactics and the overwhelming majority of charges against them were tossed by a judge who said the department lacked evidence to support the charges. Three additional suits have been filed against Craig and the department, and a Detroit police corporal was charged for allegedly assaulting three photojournalists.

While police chiefs in other cities went down for their protest responses — often, like in the case of Craig protege Hall, for coming out too strong — Craig’s tactics faced limited scrutiny from the public or city officials.

Partly, this was because Craig succeeded in short-circuiting possible sympathy for the demonstrators by painting them as misguided suburbanites draining precious resources amid a more worrisome violent crime surge. But he also played up his reputation for addressing misconduct, which includes closing the curtain on 13 years of federal oversight, introducing body cameras, and launching internal probes into corruption and racism within portions of the department. (Here too however, perception does not tell the full story. Craig has also been criticized for sweeping some issues under the rug, and, among other things, ushered in a policy to limit discipline for officers found guilty of minor misconduct and dismissed earlier allegations of “top-down, entrenched” racial discrimination found by a previous review he ordered.)

With the path cleared of obstacles locally, Craig was left to leverage the events for right-wing publicity, said Reginald Crawford, an ex-Detroit police officer, ex-police commissioner, and current president of Wayne County’s deputy sheriff's union.

“His response was designed to send a message to Washington,” Crawford said. “He was toeing this line of Trump law enforcement — this conservative law enforcement.

“Don’t get this wrong for a minute — there were sometimes people in groups throwing rocks (at police). If that happens, arrest that person. But you don’t just beat everyone; you don’t shoot journalists with rubber bullets.”

In the midst of all this, Craig took a helicopter ride over Detroit with Trump’s tough-on-crime attorney general, Bill Barr, and drew praise from the president himself, who had caught Craig on Fox News.

“You have a great police chief. I watch him, I really like him a lot,” Trump said. “He speaks so well about a very important subject, which is crime and the rioting and all the things you see in certain cities."

Coming out

In July, under the shade of oak trees at a corner park in Jackson where the historic Republican Party was purportedly born, Craig touted the party’s connection to Abraham Lincoln and delivered an abridged version of how he, a Black Detroiter who grew up in a family of Democrats, became a Republican.

It happened about 10 years ago in Portland, Maine, where he was tasked with approving concealed weapons permits. In Los Angeles, they were rarely issued, and so, instinctively, he said he began going through a stack on his desk and denying each one. That’s when staff intervened.

“They said, Well, chief, we like our guns and we believe law-abiding citizens should have the right to carry,” he explained in an interview ahead of the speech. “And you notice something else, chief — it's safe in Portland ... because criminals know ... there's a likelihood [we’re] carrying concealed.”

“It just made sense,” he told the crowd before flashing the holstered weapon in his waistband to applause.

Both origin stories were rooted in myth. The Republican Party as we know it did not end slavery, given a realignment during the Civil Rights era, and the gut instinct underpinning Craig’s political ideology is a flawed one, as research has debunked the theory that more guns equal less crime.

We can look to Detroit for clues about how Craig might fare as a candidate, which is contingent on his pulling in votes from those who approved of him as chief. A recent Target-Insyght poll showed just 14 percent of likely Detroit voters would cast a ballot for him if the election were held immediately, while a separate poll showed 28 percent would consider his record as chief in making their decisions.

But it’s more difficult to look to his past for what a broader policy agenda might hold.

Five years ago, before Craig’s audience had widened to include the right wing, he told Yahoo News that the link between poverty, a sub-par education system, unemployment, and crime was “direct” — a seeming acknowledgment that structural change was needed to lift up residents in his hometown.

Since retiring to announce his candidacy, however, he’s scantly mentioned those issues — opting instead to peddle bromides about self-reliance. On the issue of crime, specifically — his lifelong charge, and among the greatest threats facing the city he hopes to leave for Lansing — he’s grown increasingly myopic, advocating only harsher penalties for those who break the law.

For now, Craig is primarily a law-and-order candidate who concedes he has a lot to learn. In June, he indicated an agenda was a ways off, as he was getting schooled on everything from “critical race theory” to “pro-life.” The comment came in an interview with conservative Detroit News columnist Nolan Finley, who, along with the hosts on Fox News, is among the few media figures Craig has opted to speak with during this question mark phase. He even announced his campaign on Tucker Carlson’s show.

Members of his party have started to take notice of how little he’s said in early stops in Jackson and Kent County, particularly on the false notion that the 2020 presidential election was stolen from Trump, a divisive point for the GOP. Craig has come out as a two-time Trump voter, but will have to wage a balancing act to avoid alienating moderates, particularly those in Detroit.

And so it is that Hollywood Craig, once known for controlling his own narrative and never meeting a microphone he didn’t like, is suddenly unavailable. Swarmed by reporters after his Jackson speech, he ducked into a black SUV without taking questions, a politician now operating on the advice of handlers with their own PR calculus.

This story was produced in a partnership between Deadline Detroit and Detroit Metro Times.

Stay connected with Detroit Metro Times. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Google News, Apple News, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Reddit.