How an artist-turned-tech startup founder envisions a better life for Detroit’s Morningside neighborhood

The believer

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

From the open mouth of the E. Warren Tool Library in Detroit’s Morningside neighborhood, where the quiet road remains uncluttered by cars and semi-trucks, DaTrice Clark, 32, rings with hope and possibility. On a balmy August afternoon, Clark points yonder toward a lone, empty bus stop across the street. That’s where a kiosk, the anchor of a civic dream helping pull her beloved neighborhood into the 21st century, would one day live. Tall and modelesque, she moves with grace. Her voice, gentle and feathery. Her short, auburn locs shimmy like a beaded curtain.

Clark, born and raised here in Morningside, rewinds the tape of her life to a nostalgic time. She fondly remembers taking the bus crosstown with her great-grandmother as a child in the late ’90s, leaving Detroit and venturing toward the playscape inside Fairlane Town Center, about 20 miles west in multicultural Dearborn. Those rides became pasted in the family scrapbook of her mind. Those rides shaped the genesis of an idea.

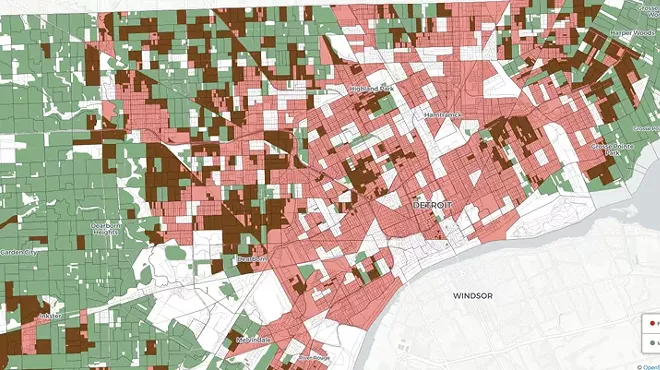

Clark founded her tech startup Crosstown Connection in 2021. The vision is simple. Kiosks, embedded with Wi-Fi hotspots, could stand along the bus route on E. Warren Avenue, a major road bisecting a majority Black community of thousands of residents, some of whom are cut off from the technology that revolutionized communication. Between 8% and 25% of Morningside households don’t have broadband internet access, according to 2021 census estimates. With the mobility-focused Crosstown Connection, people could go online for free and freely.

When the fight against the coronavirus pandemic laid bare the fragility of digital lifelines, her founder origin story began. Clark, soft-spoken yet perceptive, witnessed her community stuck in the peripheries, fending for scraps. Quarantines shuttered access to public spaces. Clark remembers seeing some people stand outside the local public library in Morningside, connecting to the Wi-Fi signal. Some didn’t have internet at home. Data plans on their phones could’ve been drained from overuse, she thought. The days of scrambling yielded moments of personal reckoning. Clark canvassed the scenes of hardship unfolding around her. When a country, a city, a neighborhood, a person hits a tough spot. “The internet is such an essential. You’re kind of left out of the digital economy if you’re not a part of it,” Clark says. “You might even miss the news.”

The bond to the people of Morningside never faded. Inside herself, a door opened. A wind of change rushing through. Clark, a longtime builder of beautiful objects, felt moved to create Crosstown Connection out of love and necessity. “What can I do for my neighborhood, personally? Because we don’t necessarily depend on all the politicians to do every single thing,” Clark says. “I just felt I had to do something.”

Clark is part of a rising vanguard. More Black women are becoming entrepreneurs across America but often struggle to secure the financing necessary to grow their ventures and remain viable through the imminent storminess of the economy. Despite these formidable odds, Clark shows resolve. She perseveres. She knows there will be growing pains, and she doesn’t seem to fret. She’ll move with care, take her time. A mild-mannered, self-professed “geek.” A multi-hyphenate, although she doesn’t use buzzwords like “girlboss” to describe herself. She is an artist, set designer, mother, and now tech startup founder, adding another title to an already colorful and capacious life.

Clark rejects imposter syndrome, a peculiar cancer of the mind that fuels self-doubt and self-sabotage. “People of color are the only people who have that. Everybody else has audacity,” she says. “I don’t like it.” In a tech industry dominated by images of white male billionaires, mentors and colleagues pour faith into the Black woman with a restorative mission, speaking about Clark in soliloquies of optimism. The one with big potential. The one with a blueprint for a better Morningside. The one built different. “I just want to help people,” she says.

Could the kiosk, made of steel, aluminum, and wood, still unscathed, withstand the brutal crawl of time? Gusts of wind? Heavy rains? “I don’t think this is its final form,” Clark says. “It hasn’t lived outside yet.” Simple and elegant, the kiosk, still a model, stands over seven feet tall and rests next to a door inside the E. Warren Tool Library, blending art, design, technology, vision with a purpose. Established in 2018, the tool library is essentially a garage where locals can borrow diverse species of rakes, shovels, power tools, wrenches, hammers, and hard hats for a DIY project of their choice. A lawnmower is left unmoored on the hard floor. Emblazoned on an exterior metal door, the library’s logo includes a circle saw and a hammer and wrench forming an X and accompanied by the slogan “LIKE A BOOK LIBRARY BUT FOR TOOLS!” inspiring a private chuckle. This is the informal showroom for Crosstown Connection and, Clark says, a community staple.

Clark’s already gotten a little money and training to refine her vision and entrepreneurial skill set. Clark, along with Ian Klipa and Jacob Saphier, the creators behind the local fabrication studio Donut Shop, won a $12,ooo grant as part of the Detroit City of Design Challenge in 2021 for Crosstown Connection. The trio received professional development and inclusive design training. Clark was responsible for the kiosk’s design, while Klipa and Saphier constructed the model, which made its debut to the public last year.

Not only do Black and brown tech startup founders often lack access to capital, they may navigate an exclusionary tech ecosystem. They may not have opportunities to fail, even an abiding faith in their ideas or a belief in the story of who they are. This past summer, Clark finished a 10-week training program aimed to uplift startup founders with a tech-based idea and aspiration called Start Studio Discovery, run by TechTown Detroit, which is headquartered in the Midtown neighborhood. Inclusivity and accessibility are ingrained in its DNA. “It’s really around creating a program that people see others like themselves,” says Christianne Malone, the chief program officer at TechTown. “We are a community for Detroiters, for people of color, to come in and be able to push whatever idea or current business to the next level through connections and collisions and resources that we’re able to provide to them.”

Clark got lessons in tech entrepreneurship 101. She interviewed a mix of residents, urban planners and civil engineers each week, part of what’s known as a customer discovery process, helping her fine-tune ideas and “get comfortable with just talking about Crosstown Connection,” Clark says. “I kind of found what I needed.” The early feedback led Clark to switch up a key concept. Initially, she wanted to retrofit existing little free libraries, or small, wooden boxes that look like tree houses, where people can borrow books, with Wi-Fi hotspots. “That wasn’t such a great idea,” she says. “People camping out on your lawn to use the Wi-Fi.” She shifted to the kiosk instead. She also talked to patrons of the local library in Morningside. They needed more internet options outside of the library’s hours of operation. Working with an anthropologist and an entrepreneur-in-residence, Clark drafted a hypothesis for why her startup should exist. The problem she’s trying to solve. Other ideas still hang in the air. She might pursue partnerships with local municipalities. Eventually, she’ll immerse herself in another iterative process of revision when she gets a working prototype. Testing. Failing. Testing. Testing again.

If DaTrice Clark’s vision meets its potential, people could furnish their digital lives. Check their email. Look for jobs. Finish school work. Watch the news. Video chat with their family and friends.

tweet this

Clark considers herself a non-technical founder, or a person with a company vision who may not have advanced coding or programming skills. The answers to her next phases lie elsewhere. “The design portion I have,” she says. “I want to outsource my weaknesses.” Ulysses Newkirk is the tool librarian and a digital steward of the community-driven Equitable Internet Initiative, which “supports and develops historically marginalized residents to build and maintain neighborhood-governed infrastructure.” A gray-bearded brainiac, Newkirk has helped households in Detroit and Hamtramck and Highland Park get online, climbing up buildings to install antennas and going door-to-door giving people routers. He adds more technical know-how to Clark’s team of collaborators.

Newkirk says he’s in charge of the labor. He’ll outfit the kiosks with Raspberry Pis, basically mini-computers that can fit in the palm of the hand. The Pi is a black, lightweight, little rectangle with a circuit and microchips, reminiscent of a toy Lego building block deserted on a daycare carpet. Right now, the plan is to convert these mini-computers into wireless hotspots. “They’re a quick and dirty solution to get something to the community fast,” Clark says.

Newkirk met Clark when she taught elementary students how to make book caddies and mini-bookshelves at the tool library last year. Newkirk found out about Crosstown Connection, so he offered to help. “I’ve been doing this. I’m good at it. It’s fun,” he says. “I don’t talk glitter. I don’t talk fashion. I talk tech.” He’s been messin’ with computer tech since 1972. He moves casually, cool and unbothered. Techie pride and history flows through him.

He poeticizes about the storage power of the floppy disk, rendered a relic of a bygone era. “We walked around with more memory than they had to put people on the moon and bring them back safely.” He reminisces about the disruptive nature of the car when it burst onto the transportation scene. “They were scaring horses off the road and killing people.” He comments on how Pokémon Go has nearly vanished from social media discourse. “It activated nearly a billion people around the world.” He quells anxious notions about how the robots will rise up and replace everyone. Technology can be a tool, Newkirk says, instead of a “weapon” wielded against communities of color.

He has high hopes for Crosstown Connection. Kids can do their homework or play their favorite game. Animal Crossing, Minecraft, Roblox. Those touchpoints could entice a younger generation to join his tribe. Newkirk stresses that Gen Z couldn’t come soon enough, pointing to a shortage of tech workers. He has high hopes for Clark, a woman with a range of superpowers. “DaTrice is the bridge for people,” he says. “There are only a handful of people in the entire city of Detroit who are effective at being both tech savvy and then community oriented.” Clark is a fluid communicator comfortable in any kind of room. A library full of rakes and shovels. A state-of-the-art tech innovation hub. A modern co-working space packed with tech developers, entrepreneurs, and investors.

Her childhood was like a montage from a beloved indie coming-of-age movie. Abounded in innocence, play and wonder, happiness. Clark lived with her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother in one of the many handsome, two-story brick houses on Balfour Street in Morningside, a 1.5 mile expanse nestled on the city’s far east side and less than four miles away from the shoreline of the Detroit River, once home to French ribbon farms, bludgeoned by the tax foreclosure crisis, enlivened by a block club as well as community-driven organizations, a greenspace boasting perennial crops of broccoli, kale, and swiss chard, and Morningside Cafe, a small business reborn after a fire. “The most beautiful neighborhood in the city for real,” Clark says.

While Morningside endured ups and downs, Clark’s eyes glow big, recounting her youth’s idyllic adventures. She’d play basketball with her cousin. She’d buy fruity-flavored, pink and blue penny candies from a corner store. She’d go roller skating at Skateland. She’d devour Brothers Grimm books. She danced and danced. Liturgical ballet and jazz for 10 years. She’d make beaded bracelets and necklaces her mother Tamiko Clark, a longtime public school teacher, would show and sell to her coworkers, a preamble to her daughter’s entrepreneurship in adulthood.

Those early years, her mother remembers, revealed a creative mind that’s since grown nimble and strong. “None of what she’s doing right now really surprises me,” her mother says. “You know how they say women like fancy things? She likes those things, but the way to her heart is if we give her a Home Depot gift card, or Lowe’s gift card or something like that, or some tools. She’ll be more grateful.”

Her mother has a flair for style as a green streak flashes across her dark hair like a bolt of lightning. She is just as soft-spoken and artistic as her daughter, making candles as well as self-care themed, paperback journals she sells on Amazon. She’s busy too, teaching teenagers A.P. African American History at a charter school. The lessons are tough. She’s been a little tough on them, as you’d expect a teacher who cares to be. She still shows up for her daughter, acting as a bedrock of moral support. She knows her daughter can find her own rhythm, and she’ll be fine. The mother believes her daughter will always be fine because she’s got a wealth of knowledge, always reads, always tries.

The mother doesn’t worry too much about her daughter’s future. She trusts her. She knows her daughter doesn’t have to ascribe to what she deems an arbitrary timetable for success. “It’s kind of a false narrative,” she says. “‘You’re 30, should be married, or you’re this age, you should have bought a house by now.’ Those are things based on capitalism. Those societal things that are considered norms.” She believes success looks different for everybody. The small, everyday wins hold startling weight. “It could be simply, ‘I got out of bed today. And that’s more than yesterday,’ right?’”

She pulls out her smartphone, scrolls through her daughter’s Instagram account. A sparkling mosaic of color and sunlit selfies and the milestones her little girl who loved making jewelry has already fulfilled. A picture of her, all grown up and capable, now sculpted in the cool girl mold. Think Solange. The same picture of her wearing a beige bucket hat, a white tank top, and jeans and caressing a wall of soft strips of pink, purple, orange, white, blue braiding hair, an artistic ode to Black natural beauty, that made Vogue’s website. The same picture that’s also documented proof. She knows she did right by her daughter. She’s proud of her. Clark grabbed the wheel and drove toward her destiny.

In the Corktown neighborhood, Newlab is housed inside a 270,000-square-foot space well known for its past incarnations: an old post office and the Book Depository Building, where Detroit Public Schools once stored crayons and sports equipment. Unveiled in the spring, the building has been revamped into a home for start up businesses such as Vela Bikes, RoboTire, and JustAir. Newlab is part of a 30-acre innovation district developed by the Ford Motor Co. that promises to “reshape the future of global mobility.” Nearby stands the grandiose Michigan Central Station, a former railway depot, once serving soldiers going off to war and vacationers and factory workers, once serving as a poster child of the city’s decline that’s poised for a revival.

A hum of activity sweeps across the first floor of Newlab, the touch screen-equipped elevators, the sneaker display, the electric vehicles decorating pristine halls so spacious free thinking luxuriates. Hundreds of people, the gregarious, the introverted, trickle into a networking event called Black Tech Saturdays, a regular weekend gathering taking place on a brisk afternoon in early September. On the agenda is a lengthy panel discussion and Q&A forecasting the future of Michigan as a leader in the tech innovation space. On the lunch menu is falafel, salad, and lemonade.

“Demystifying tech” is the mantra for a networking event hoping to spur a local tech revolution led by a Black and brown workforce. “Most of us don’t have dreams of becoming disgustingly wealthy. Like, no one’s trying to be an Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos. Nobody wants $200 billion,” says Johnnie Turnage, 29, a grassroots community organizer. He and his wife Alexa Turnage co-founded EvenScore, an impact-focused, community building platform and co-created Black Tech Saturdays. “Everybody’s like, ‘Yo, what if this were better? It could help the community and I’m not the only person who sees this as a problem.’ And I think that’s the part that sometimes can be a little wonky for us, like, we do just want to change the world.”

A life-altering eureka moment can be followed by a flood of soul-searching questions. “You have an idea of a problem you want to solve. A company you think could be great,” Turnage says. “And the first step for most founders is figuring out how to validate the idea in any way. Do people want this?” This is part of what Turnage dubs the idea stage — validators could be potential customers testing out a beta version of a product. They could confirm to a founder that their endeavor is worthy of all the hours of sweat equity needed to transform a risk into a rewarding business. Founders need lots of validators. One way to get them is through a startup accelerator, or a type of business program — run by corporations, venture capitalists, or other entities — that usually provides education, mentorship, and financing to early-stage founders for several months. Turnage points to a few local examples of big-name accelerators, including TechStars Detroit, geared toward supporting entrepreneurs of color.

Still, funding disparities and discrimination persist. In the United States, Black startup founders, working in tech fields and beyond, receive less than 2% of venture capital funding each year. Black women founders secure less than 1% of VC dollars, according to Crunchbase. In the wake of the killing of George Floyd, Black founders and Black-led startups saw historic year-over-year gains in VC fundraising in 2021, CNBC reports. Worsening market conditions and fizzling momentum to honor a diversity mandate saw VC financing for Black founders nosedive last year. Some women of color founders say they’ve faced explicit racism and sexism from advisors as well as investors, most of whom are white men.

For many Black and brown tech startup founders, breakthroughs are hard, Turnage says. They may face skepticism of their abilities. Can they succeed? Even their presence can feel like a shock in spaces of homogeneous thought and background. “Maybe you talk different. Maybe you dress different,” Turnage says. “You’re walking into a room oftentimes feeling like ‘I’m just here to be seen. No one’s listening to me.’ So you have to, like, learn how to very quickly tell your story in a way that relates to an audience. You might be in a room with a bunch of affluent white males who come from Grosse Pointe, and you’re talking to them about these communities [that] don’t have Wi-Fi and they’re like, ‘What do you mean, free Wi-Fi?’ The hard part is they might not even understand the problem. But that’s lived experience.”

That scenario of misunderstanding can reinforce a corrosive internal script. A sense of shame of who they are, Turnage says. Founders of color are navigating a startup ecosystem that may fail to recognize their lived experiences as valuable expertise. A competitive advantage in and of itself. When the tough times hit, when mistakes empty their bank accounts, some founders can’t get bailed out by their families. “We all inherently know. We can’t afford to fail,” Turnage says. “The pressure is there. We’re trying to be perfect. But the truth is, real tech is sticky. It’s messy, right? Put on a product, see what people say, [make] adjustments. Well, if I don’t have the capacity to throw out a product, get feedback, and spin it up. A lot of us are like, ‘Well, if I put out a non-perfect product, it’s gonna ruin my reputation.’”

Launched in April, Black Tech Saturdays serves as a gateway to learning, resources, investment, collaboration, and empowerment for tech entrepreneurs of color, absent any insider jargon that can be, at times, alienating for the uninitiated. “What does that mean? How does that work? For all I know, there can be 10,000 people in the city of Detroit who have way better ideas than all of us,” Turnage says. “There are entrepreneurs who are fairly successful in Detroit, maybe they don’t know the tech part. Maybe they need to come here and listen to somebody who can say, ‘Well, let me break it down this way for you.’”

At the networking event, the vibe is unpretentious and laid-back, refusing to cater to a suit-and-tie, Ivy League crowd and an expectation of code switching. Turnage, hailing from the city’s east side, has the warmth of a life-size teddy bear with a penchant for breaking the ice with strangers by asking them what their superhero origin story is. Attendees chatter during a short, speed networking activity, encouraging the mostly Black and brown tech startup founders, among them Clark, as well as software developers, investors, graphic designers, hiring managers, and the tech-curious to meet-and-greet and discover their next dream partner. Matchmaking can be the ticket toward reaching their professional destinations.

Clark is a regular of Black Tech Saturdays. Turnage met Clark at a recent tech conference in Cincinnati. Her confidence made an impression, and the two clicked quickly. Already, Turnage is one of her validators, giddy over the potential of her vision. “If she figures out a way to solve the digital divide for Morningside, if she figures out a way to make them more connected, she can take her solution and sell it to other cities, other neighborhoods around the country,” he says. “No one’s going to try to solve it like DaTrice. And I would argue there are places that DaTrice can walk into that any other founder from a different demographic won’t be able to walk into.”

As the convening wraps up, attendees scurry into the elevators and go up to the second floor, the site of a tall, silvery staircase. A drone camera buzzes near the fronds of a cluster of lush plants. Together, attendees congest the steps and pose for pictures like a tight-knit class of graduating high school seniors, invigorated by the atmosphere of openness, the fellowship, the shared faith in their dreams and ambitions. Clark is bubbly, all smiles. “To see people who look like me means so much, because a lot of the entrepreneurial journey can be isolating,” she says. “I’m feelin’ good.”

It would take 50 minutes riding two city buses to travel about 10 miles from Morningside to downtown Detroit’s concrete metropolis, away from the quiet roads peppered with humble homes and humble stores toward skyscrapers reaching the clouds. Skyscrapers that form a skyline that’s been immortalized on stickers and T-shirts. The changes in scenery are startling reminders of all the inequities a single city can hold. On this ride, passengers could steal glimpses of big-time venues. Little Caesars Arena, the home of the Detroit Pistons and the Detroit Red Wings. The Fox Theatre’s digital marquee broadcasting upcoming comedy and concert shows flanked by a pair of winged lions. A few blocks away stands the six-story Julian C. Madison Building, named after a pioneering Black engineer. Beams of sunlight shine through wide windows of one the building’s top floors, overlooking a city of endurance, a city of hustle, a city of dreams.

In suite 301, Bamboo Detroit, a co-working space, hosts a pitch night for a handful of startup founders on an early Tuesday evening. A chance to get live feedback in a friendly environment. The room is striking in its hospital-level cleanliness. There’s a kitchen and a flat-screen TV, and people already seem to be in a collegial and upbeat mood among the roughly two dozen, clean cut, smartly dressed professionals. Different ages, different races, different genders. Some are nibbling on mini-plates of buffalo wings and barbecue wings and sticks of carrots and celery. Clark is the fourth founder slated to present. She’ll follow pitches for software apps on caregiving, language learning, and voting information targeting Gen Z and millennials. This night is a test-run of their storytelling powers. Pitching is an important skill founders must master. They must sell their company visions and themselves.

After 6 o’clock, Clark approaches the front of the room. Wearing a flowy, black sheath dress and a pair of beige cowboy boots, her locs are now blonde and coiffed into an updo. She’s welcomed by a crackling of applause. The flat-screen TV displays a powerpoint presentation. Clark hits all the bullet points of her pitch in just a few, allotted minutes. First, she drifts into her childhood: walking with her great-grandmother to the library on E. Warren and Outer Drive in 1998. The same library, 25 years later, residents of the eastside of Detroit and Morningside would rely on to go online, connect to the world. That’s her hypothesis. All eyes are on the daughter of Morningside. The screen flashes graphics showing an attention-grabbing statistic: 70% of school-age children in Detroit don’t have internet at home.

“This digital redlining excludes people of color from opportunities afforded to those with the ability to get online,” Clark says. “We’re missing out on chances.” On getting jobs. On getting a college degree. On just being together. Along with her collaborators at the Donut Shop, Clark came up with a solution. The kiosks. Free and secure Wi-Fi. They could live along bus routes. They could live inside public parks. From wall to wall, Clark is a natural public speaker, her eyes focused, her voice unfaltering, commanding attention.

If her vision meets its potential, people could furnish their digital lives. Check their email. Look for jobs. Finish school work. Watch the news. Video chat with their family and friends. Get updates when the lights turn off at home. Explore, explore. Clark needs hardware and software, so she can build a working prototype that’s powered by solar energy. As her pitch ends, she answers a hail of questions from the crowd. Are you not concerned about vandalism? No, she says.

She doesn’t want to price out the users she’s aiming to help, the people of Morningside. She gets into a rhythm, fielding more questions about security and the weather. She doesn’t get flustered by the rattling noises of ice cubes scooped into a cup. The car horns shrieking outside. The eyes laser-focused on her dream. She ends her presentation looking clear-eyed and confident. Not a hint of hesitation. Only unwavering belief.

Clark has always been a maker of beautiful objects. The beaded jewelry. The designer clothing hacks. Backdrops for glamorous photo shoots. Backdrops for late-night dance parties brimming with tequila shots and twerking. She doesn’t want to just build shiny and pretty things that could be quickly torn down and forgotten. “What’s going to make an impact?” Clark says. “What’s gonna live longer than you?”

Legacy-speak can arrive at the dawn of the thirties. Clark turns 33 in November. While the dream of legacy has come into her thoughts, she’s in no rush. She’s not wooed by the glamorization of the grind culture. She’s got a day job at an event production company. She has a young son she’s trying to raise into a man. “Some things take time. And that’s OK. And I’m OK with it because it’s going to serve the community” she says. “I’m not going to be good enough if I’m going to be broken down.”

Clark’s searching for her people in tech. Perhaps down the line, she’ll encounter naysayers and doubters. Even then, she’ll be an ambassador for her neighborhood wherever she goes. Who will she meet? Who can she trust? Who believes in her story? Who believes in her too? She’s taken a chance. She’s bet on herself. She’s dreaming ahead. A kiosk could be a monument to a better life in Morningside.

Subscribe to Metro Times newsletters.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter