Lillie McGee swings closed an entry door to her apartment building on Detroit's west side to show how it rests on its frame without shutting. Squatters, she explains, are able to access the building, and have at times taken up residence in the vacant units that surround her home.

"And here I thought I had new neighbors," McGee, who's asked we withhold her real name, says wryly.

Inside her spartan two-bedroom, the stove top is cluttered with pots she says she uses to boil water to bathe. The hot water has been out for months. Last winter, the heat didn't work.

The problems are not unique to this building, McGee says. As a lifelong, low-income renter in the city of Detroit, she's accustomed to living in poor, and at times unsafe, conditions. At other rentals, she's endured roach infestations, leaky ceilings, mold.

"It's always been difficult to get landlords to respond," she says. "Some would just be like, 'If you don't like it, find someplace else.'"

Once, in 2010, McGee withheld rent with the hope that it would prompt her landlord to deal with a roach problem. She was evicted and sent scrambling to find a place to live. Unable to qualify for several apartments within her price range, she wound up moving into a hotel.

McGee's plight is typical for a low-income renter in Detroit. Tenants in at least one in every five of the city's rental properties face eviction each year, often for withholding rent over unlivable conditions, according to a Detroit News investigation published last year. Part of the issue, the News found, was the city's lax enforcement of building and safety codes. As of last year, just 4,200 rental units had been inspected and registered with the city, as is required by law. There are 140,000 total rental units in Detroit; inspections are required each year.

In order to get a handle on the problem, the city in February launched a massive undertaking to get landlords to register their rentals, undergo inspections, make the necessary repairs to bring their properties up to code, and obtain certificates of compliance. The program is being phased in throughout the city, with all zip codes required to be in compliance in 2020.But while the rental inspection and registration program is designed to improve living conditions for people like McGee, there's fear that it will squeeze mom and pop landlords along with the big slumlords the city is targeting — leading to rent increases for Detroiters who can least afford them. The thought is that by requiring landlords to make improvements that housing industry experts say can cost up to $10,000 per standard single-family home, landlords will be forced to pass the cost on to tenants, taking rents up 25 to 50 percent, by at least one property manager's estimation. If they can't charge enough in rent to recoup what they've spent on the property, landlords are expected to sell, in some cases to speculators or to tenants through precarious land contracts that often result in eviction. Both scenarios could jeopardize Detroit's already dwindling supply of low-cost rental housing and further destabilize its neighborhoods as evictions threaten to bring about more vacancy and blight.

As part of the rental registration program, landlords must pass a lead inspection and have their taxes and any outstanding blight tickets paid. Landlords who don’t comply are threatened with stiff penalties, including monthly blight tickets for failing to register the property and get a lead clearance — which together total $750 — and the loss of months’ worth of rent, as the city encourages tenants to escrow. Criminal charges are also a possibility.

Early signs show landlords at the overwhelming majority of the city's rental properties may have trouble or be unwilling to make the requisite improvements. Compliance rates are abysmal in the first two zip codes where the program has been fully or almost fully implemented. On the city's far east side, in 48215, where a six-month deadline for improvements came up Aug. 1, landlords brought up to code just 11 percent of properties. In neighboring 48224, just five percent of properties have been brought up to code ahead of that zip's Sept. 1 deadline.

With so few rentals in compliance as the ordinance goes into effect, the unknowns are tremendous. There's also nowhere to look for clues on how this might shake out. No other major city in the country — let alone one as economically distressed as Detroit, and with housing stock as old — is known to have attempted such wide scale enforcement of its property maintenance codes in such a short period of time.

"We're the first city out to shoot in developing this process," says Mark Kincannon, the project manager on the rental inspection program. "Everybody's watching us."

But housing advocates warn that, when all is said and done, Detroit will not be a city known for providing particularly safe living conditions. Rather, it will be beset by displacement and disinvestment as a result of its own negligence.

Said Amina Kirk, with the nonprofit advocacy organization the Detroit People's Platform, "It's irresponsible to draft an ordinance that has this large of an impact on our low-income housing stock without being very careful and conscientious about ensuring that it does not result in displacement."

'The economics just don't work'

Taylor-based Garner Properties began to shed its single-family rentals in Detroit several years ago, when it first learned the enforcement effort was on its way. In 2015, the company was managing about 500 single-family homes for smaller investors; today it's down to 125.

"There was just no way to make the numbers work," says company president Chris Garner. "So we started telling our investors to start pulling out and we decided to stop managing properties in the city."

Detroit has long been a minefield for small landlord investors, Garner says, with the low price of real estate offset by high taxes, insurance, tenant turnover, theft, and the cost of maintaining old homes. Now, with tougher regulations that can require thousands of dollars in repairs on the average single family home, Garner says there's little incentive for his clients, who each own about three to seven single family properties, to do business in the city.

According to Garner and a real estate agent with whom we spoke, the average cost of upgrading a single family home to comply with the rules ranges between $4,000 and $9,000. Lead inspection fees and the cost of encapsulation runs about $1,800 in homes built before 1978, when lead-based paints were outlawed, and additional repairs, which Garner says can often include things like electrical system upgrades and replacing cracked slabs of porch concrete, cost between $2,000 and $5,000.

"Most investors that are our clients don't have a problem with making a property habitable, but most of these houses are 70 years old and the city is sometimes requiring they be brought up to new construction standards," he says. "To invest $6,000 on a property you're getting $650 in rent for — the economics just don't work."

Tenants putting their rent in escrow also eliminates a source of revenue with which landlords can pay for repairs.

While Garner anticipates a small portion of landlords will raise rents to recoup the cost of improvements on their properties, he says that in most Detroit neighborhoods, there's just not enough demand to cover the necessary increases. By his estimation, $9,000 in repairs on a single-family home would require an independent landlord to raise rents by 25 to 50 percent just to maintain an average profit margin of six to eight percent.

Some Detroit landlords or would-be landlords are expected to head to the suburbs for better returns. Derek Werenka, the owner of M-1 Realty, has been telling clients to budget an additional $10,000 if they plan to purchase a single-family rental property in Detroit, and suggesting they consider areas like Hazel Park and Hamtramck instead.

"For a three bedroom, one bath brick house in Detroit where you can get about $700 a month in rent, now it's going to cost you $60,000 or $65,000 to purchase and get rehabbed," says Werenka. "Well, you can get a three bedroom in Hazel park for the same price and charge $900 a month for it, so while the housing stock isn't as great, the [return on investment] is way better."

Meanwhile, additional signs are emerging that landlords are pulling out of Detroit. In January, Bryan Knisely, president of the Las Vegas-based Knisely group, says he was offered a "too good to be true" package of 15 single-family homes for $20,000 a piece, with the option to buy up to 100 down the line. After soliciting Werenka to help to look into the portfolio, Knisely says "we finally realized why the seller was probably selling at that price — because he was going to get hit with having to get his stuff up to code."

Using the $10,000-per-home rule of thumb, Knisely walked away from the deal.

"It threw our yield and we weren't willing to take the chance," he says.

Strained supply

McGee is one of the many casualties of Detroit's affordable housing squeeze. In 2010, after being evicted for withholding rent at the roach-infested apartment, she was forced to look for a new place within her approximately $600-per-month price range. Despite making $27,000 annually at the time as a home health aide to cover living expenses for herself and her partner, who has a disability, she says she was denied housing at at least a half-dozen rentals because her income was unstable and she had bad credit. When she finally found a place that would take her, she says the property manager canceled the deal when she came up $5 short on a $1,025 payment for first month's rent and security. McGee gave up and moved into a hotel, where she stayed for the better part of a year.

"It's very difficult to find a place because you have to have like $2,000 in the bank or established income per month," she says. "The application for the lease is $25 or $35, and you pay them to do the application, [and then] they just take your money and they say, 'We can't rent to you.'"

As for government-subsidized affordable housing, which the city says accounts for less than 9 percent of its occupied homes, McGee says “there are so many qualifications … a lot of people don’t have ID and can’t do a background check.”

As a result, today, McGee is severely rent burdened, paying $700 a month for rent and utilities in the two-bedroom with no hot water. She says that leaves her with just $200 in discretionary spending each month.

"They know people are desperate to have a place to stay and they'll go for anything," McGee says.

About a quarter of Detroit tenants are in McGee's position — severely rent-burdened and paying more than 50 percent of their income on housing and related expenses. About 60 percent spend more than the recommended 30 percent of their income on housing expenses.

‘They know people are desperate to have a place to stay and they’ll go for anything.’

tweet this

The struggle is the result of rising rents outpacing household incomes. It's a nationwide predicament, but in Detroit, wages have actually fallen as rents rise. Average rent in the city is $820 per month, up from $650 a decade ago, according to a study released by the city this year. Meanwhile, median wages have fallen by 20 percent over the same period to about $20,000, according to federal statistics recently pulled by Bridge magazine. These dynamics prompted a separate study to conclude that Detroit suffered from the fifth-worst rent increases of any major city in the nation between 2013 and 2016.

While affordable rental housing is often subsidized by the government, in Detroit, the majority of affordable housing is “naturally occurring,” meaning market forces have kept it at rates affordable for households earning up to 60 percent of Area Median Income, or approximately $33,700 per year. That means rent and utilities at such properties come out to about $840 a month or less. The median income for a Detroit household is about $28,000 — less than half of Area Median Income, a government calculation that uses incomes throughout the region.

The city is in the process of determining just how much of its housing is naturally affordable, but has estimated that it accounts for more than two-thirds of its unsubsidized multifamily units.

Kirk, a legal and policy advocate with the Detroit People’s Platform, says she’s most concerned about the impact the rental inspection and registration ordinance will have on this unregulated affordable housing.

"The city constantly refers to the naturally occurring affordable housing stock as a key component of its plan for providing affordable housing in this city, [but] it doesn't seem to have contemplated the fact that naturally occurring affordable housing is usually owned by independent small landlords who do not make a great deal of income off of those properties," she says.

Kirk says that while she agrees with the city's goal to provide safe and livable and conditions for residents, she says more steps should have been taken to give landlords a better chance to comply with the requirements.

Adjustments the city could make, Kirk says, include providing funding to help mom and pop landlords meet the terms of the rental ordinance. Specifically, she suggests the city secure additional revenue streams for its so-called "affordable housing trust fund," which right now relies on a portion of the net receipts of city-owned commercial property sales. She also says landlords could have been given more time to comply with the rules, and that the various code requirements could have been implemented piecemeal — with lead compliance first, followed by less hazardous blight violations.

Indeed, there is broad consensus that something must be done to improve the condition of the city's older homes, as their deterioration not only jeopardizes the health and safety of residents, but threatens the sustainability of the city's affordable housing supply. In a report released earlier this year by the Urban Institute, authors Mark Treskon and Carl Hedman described upgrading the city's affordable housing supply as key for its preservation, but also acknowledged the problem is cyclical: Landlords who rent to lower-income populations can't raise rent to make upgrades, leaving conditions at Detroit's properties to deteriorate.

"Over time, this has led to significant abandonment and inadequate housing across much of the city and relatively lower levels of affordable and decent housing stock," the authors wrote.

While the Urban Institute report saw the rental inspection and registration ordinance as having the potential to help improve the condition of the city's low-income housing supply by identifying at-risk properties, it suggested that the city take steps to avoid deterring landlords from doing business in Detroit. Like Kirk, the authors said the requirements could be linked to rehabilitation funding — pointing to a low-income housing preservation program in Chicago, the Troubled Buildings Initiative, that uses federal grants to help landlords pay for repairs identified by code officers. According to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the program costs around $5 million to $6 million a year and is paid for primarily through Community Development Block Grants and additional private funding. It has led to the preservation of 16,000 naturally occurring affordable housing units since its inception in 2004.

It's worth noting that Detroit itself appears to have come to the conclusion that costly repairs can result in rent hikes and the displacement of residents. In its Multifamily Affordable Housing Strategy report released this year, the city said that while it is "interested in continued investment and improvement of housing quality in Detroit, rehabilitation or renovation of occupied buildings threatens to displace existing residents who cannot afford increased housing costs." The statement is wedged in a portion of the plan that describes tax incentives as "critical" to "the financial feasibility of operating affordable housing," both regulated and naturally occurring.

No plan for fallout

Though some say the city should ease the burden on landlords given the unique nature of its housing stock, officials argue that's the very reason such stringent requirements are needed. In 2016, nearly 9 percent of Detroit children tested for lead poisoning tested positive — the most of any city in the state — primarily as a result of unabated lead paint in households built before 1978. In written responses to a series of questions from Metro Times, the city said that, additionally, its rental intervention is warranted because of the age of its homes and "an enormous amount of blight conditions creating unsafe housing."

Detroit is also home to a vulnerable population that can easily fall prey to slumlords looking to make a quick buck. Predatory investors, for example, will buy houses for just thousands in the Wayne County tax foreclosure auction and "rent" to tenants without ever paying the taxes on the home, leaving the tenants to be evicted three years later when the home is foreclosed and sold at auction once again. Properties frequently switch hands with people in them, and with no outreach from the new owner, tenants have no idea who to contact for repairs. In researching this story, we learned of several "ghost landlords" BSEED has been trying to identify — faceless LLCs that own dozens of properties they collect rent on and leave to rot with people inside.

Then there are the high-profile violators like the Hagermans, a father-and-son team known for scooping up thousands of homes in the Wayne County Tax Foreclosure Auction and renting them out, often to the very people who lost them for a back tax bill worth as much an iPhone. While not as bad as others, father Steve Hagerman recently became an example for landlords who flout the rules when he was reportedly sentenced to 60 days in jail after the city cracked down on his company for numerous safety and health code violations at a home, including the apparent presence of black mold.

"It's bad landlords we're trying to get our arms around," Mark Kincannon, who is overseeing the rental inspection program for Detroit's Buildings, Safety Engineering, and Environmental Department, told us. "We're not targeting the mom and pops, the people who have one to two homes. We're targeting the big ones that are causing problems for people, because they have hundreds of properties that they're not maintaining."

‘Many landlords have been collecting rent for years and not using that money, as they should have, to bring the properties up to code. Taxpayers shouldn’t have to pick up the tab for that.’

tweet this

But there are not two sets of rules for landlords with a flagrant disregard for the law and the small guys who wish to comply but may lack the means.

In their written responses, higher-ranking city officials took a harder line than Kincannon — putting the blame on landlords, broadly, for failing to comply with codes the city hadn't consistently enforced over the years, defending the amount of notice landlords were given to make repairs, and sidestepping questions on what impact the ordinance would have on the availability of affordable housing in Detroit.

"Many landlords have been collecting rent for years and not using that money, as they should have, to bring the properties up to code," said chief of services and infrastructure Arthur Jemison. "Taxpayers shouldn't have to pick up the tab for that."

"The point of affordable housing is for it to be safe, clean, and decent," he added. "We do not accept that in order for there to be naturally occurring affordable housing it can't or doesn't have to be up to code."

Jemison did acknowledge that properties will likely flip and that the state has no laws limiting rent increases.

"Rent will fluctuate until it reaches an equilibrium based on competition and affordability," he says.

Meanwhile, Kincannon, in our conversation, framed the looming sell-offs as a positive.

"There's going to be a turnaround, but if they do [sell], they're doing it at the right time, because there's so many people here that want to buy into the city of Detroit," he said. "So it kind of benefits the tenant because your new landlord is coming in saying, 'Hey, I want to buy in Detroit, and so we're [telling them] you got to register your property.'"

Incorrectly, he said he believed landlords in the city were barred from "arbitrarily jacking up rent." He also appeared to think there was a plan in place to prevent displacement.

"That's something the mayor has talked about," Kincannon said. "I don't know much about the details — but he's keeping an eye on it. They're making sure they don't run regular Detroiters out, so there is a cap [on rent increases]."

Kirk, with DPP, says that in talks with the city, the organization was met with similar responses when it asked what would happen to low-income tenants and independent landlords.

"In speaking to all the powers that be — whether it was the Department of Neighborhoods, BSEED, or [councilmember Andre Spivey,] who drafted the ordinance — they weren't at all concerned about any of these issues," she says. "Which means they're just not concerned about the massive displacement that may occur as a result of this ordinance."

Notably, the city says only BSEED and its Law Department crafted the amended ordinance. The Department of Housing and Revitalization was not a part of the process.

Bracing for impact

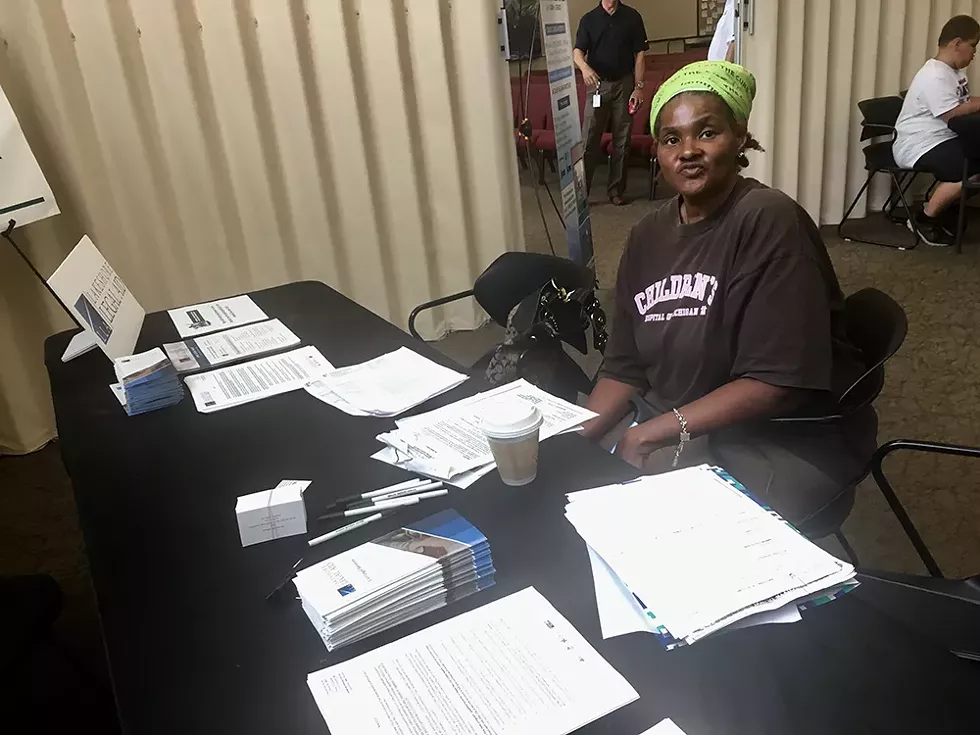

On a recent Saturday morning at a Salvation Army on the east side, representatives from the city guided a steady stream of residents in the 48215 zip code through the process of withholding rent.

It was the first in a number of "escrow fairs" to be hosted in areas where landlords had failed to get their properties up to code by their given deadline — a sign that city officials were making good on their promise of consequences for those who don't comply.

Since the Aug. 1 deadline in 48215, the city has issued more than 1,000 tickets of up to $750 each to landlords in the zip code, with additional rounds of tickets to follow each month. The city has helped at least 14 residents withhold their rent.

What happens next is the big variable — the city has said renters will not get evicted for withholding, but legal counselors on hand at the escrow fair cautioned otherwise.

"If these folks are not represented by attorneys once we get to court, there's a high likelihood that they're going to be facing eviction," said Ted Phillips, director of the United Community Housing Coalition. "We've already got people who've been evicted this year who are living in homes that are tax foreclosed — not even owned by the [person who claims to be the] owner — and those folks lose in court extremely easily when they're not represented."

In anticipation of being "totally and completely overwhelmed" by demand for its legal and housing placement services, UCHC has submitted a grant request for an additional attorney and legal aid at its clinic outside the 36th District Court's landlord-tenant division. But the resources will only go so far — the organization is set to lose nearly half of its budget by year end due to cuts in federal funding.

The increased staff capacity, Phillips says, is needed not only to represent eviction actions brought against tenants as a result of their escrowing rent, but to help them in the event that property sell-offs materialize in the form of precarious land contracts.

"I expect some cash sale deals where landlords get out entirely, but I expect massive sell-offs under land contracts, because as soon as the person defaults they can go after them and evict them," says Phillips. "So they've got best of both worlds, they've transferred their obligation of doing repairs to the tenant/buyer and they still keep the property."

Ultimately, Phillips sees the ordinance as necessary for ensuring better living conditions for renters in the city, and is hopeful that with the right support, the possible negative consequences could be turned into positives.

"If we had valid honest sales arrangements between landlords who want to get out and tenants, and make sure that the city is granting poverty exemptions [to the buyers] that qualify for them," he says, referring to a program that can lower or eliminate the property taxes for low-income owners. "There's also going to be a number [of landlords] in serious tax arrears, and maybe next year's [Right of Refusal program] might find a bunch of landlords who've walked away so we could make those tenants owners."

As things unfold, McGee has been mulling what she may do when the ordinance hits her zip code, where the compliance date is Dec. 1. Initially, she said she was leaning toward avoiding escrow because she didn’t want to risk getting evicted. Her partner has one leg, all of his doctors are near their home, and neither one of them has a car.

Then, on Thursday, McGee was suddenly served with an eviction notice because she was behind one month in rent. She’d been set back by the cost of a family member’s funeral, but said she had worked out a deal with her property manager to pay her July rent late. Since then, however, the property had come under new management.

Now, McGee heads to 36th District Court for an unexpected hearing, another Detroiter fighting to hold on to a substandard home.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.