Gilbert's Bedrock says it will create 'affordable' housing in downtown Detroit. Here's what that actually means

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

This week, Bedrock — Detroit's largest developer — announced that it would create or maintain 700 "affordable" units in greater downtown Detroit as part of a commitment with the city to redevelop the area as an "inclusive, mixed-income community."

The "affordable" units will make up 20 percent of the 3,500 residential units Bedrock plans to develop over the next several years, putting the real estate company owned by Dan Gilbert in line with Mayor Mike Duggan's affordability requirement for residential developers receiving certain things from the city.

Bedrock

Bedrock's 28Grand building in Capitol Park will include 85 units for households making 60 percent of Area Median Income.

This year, the federal government calculated AMI for a family of four in the region at about $69,000 per year. In Detroit proper, however, median household income is listed at around $26,000. The city and Bedrock are basing affordability on the regional average.

To put that in terms of single-person household incomes, someone making 80 percent of AMI makes a little over $38,500 per year. Their rent would then be reduced to make sure they spend no more than about a third of their income on housing and utilities.

While that may sound progressive, a recent study commissioned by the city found it doesn't actually address the greatest housing need in Detroit. The study by real estate firm HR&A Advisors found that 97 percent of rental units throughout the city are already affordable for households making 80 percent of AMI. Meanwhile, 86 percent of Detroit's rental units are affordable for those making 60 percent of AMI.

It's people living at 30 percent AMI and below who would benefit most from the housing help. The HR&A study found that for those poorest Detroit residents, just 23 percent have affordable housing options. But the city's housing and revitalization director has pointed out that developers can't provide units that cheap because they would lose money on their projects.

While 54 of Bedrock's affordable units will be designed for people living between 30-60 percent AMI, affordable housing advocates say several dozen such units will do little to address the rapidly dwindling supply of adequate affordable housing in Detroit.

"There are far more already existing affordable units disappearing than there are affordable units being built and preserved," says Aaron Handelsman with the Detroit People's Platform, a network of Detroit-based social justice organizations. "So there's already a gap and the idea that [Bedrock is] doing anything to help plug the gap is misleading."

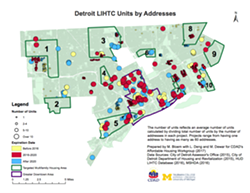

Yet, Detroit officials framed Bedrock's low-income units as helping address the rental assistance expirations looming for people at 2,000 units in the city. Researchers at the University of Michigan have found much of those are located in the greater downtown, where, without intervention, expiring units will likely flip to market rate and drive longtime Detroiters from their homes. More than 2,000 units receiving the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit will have expired in that area between 2016 and 2020.

But even if Bedrock's affordable rental units

Map of Detroit rentals with expiring Low Income Housing Tax Credits.

Regardless, when developers are championed for creating and maintaining "affordable" housing, it helps to put what they're offering into context.

Not one media outlet that covered Bedrock's announcement explained the difference between AMI and median Detroit household income (we're lookin' at you, WDIV, WJBK, D Business, and Curbed. Crain's too, but at least it put affordable in quotes). Noting that affordability rules in Detroit — a city where 40 percent of households live in poverty — are not exclusively based on the incomes of Detroit residents seems like a key step in covering developers who claim to be working to make Detroit's most wealthy areas "inclusive."