Excerpt: New book ‘Plundered’ examines the racist policies behind Detroit’s foreclosure crisis

The story of Detroit and many other cities across the U.S. are tales of predatory governance

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

As a law scholar, author, and leader of the Coalition for Property Tax Justice, Bernadette Atuahene studies the impact of systemic racism on homeownership. A 2018 study by Professor Atuahene and Christopher Berry of the Center for Municipal Finance at the University of Chicago estimated that 1 in 10 tax foreclosures in Detroit between 2011 and 2015 were caused by the city’s unconstitutionally high assessments. Twenty-five percent of tax foreclosures of the lowest-valued homes were due to unconstitutional assessments. Professor Atuahene’s new book Plundered: How Racist Policies Undermine Black Homeownership in America (out now by Little, Brown and Company) begins with the following anecdote, which has been edited for length and re-published here with permission.

Ms. Mae, born in 1945 as Anna Mae Jackson, has lived in Detroit her entire life. Distinguished by her soft silver Afro, dark sun-kissed skin, paisley walking stick, and radiant smile, she says she never allows her troubles to steal her joy, and loves “talking spicy” in order to make folks laugh. Ms. Mae most looks forward to the summertime, when she can be out on her spacious porch chatting with her neighbors for hours on end.

“I’ve been in this house for fifty years,” Ms. Mae explained from her customary seat on the porch. “At one time I didn’t feel safe ’cause somebody climbed in my bedroom window. It was morning time, in broad open daylight. I was sitting up here in the front room and when I looked up and seen this man standing in my hallway, I started shooting at him. He left the sole of his shoe in my bed, and he went out through the alley.” In 1970, when Ms. Mae first moved in, there was an icehouse behind her property that attracted significant foot traffic and all manner of people from outside the area, including the intruder. Ms. Mae continued, “But since then, I’ve had no problems and feel safe in my house.”

Despite the slow decline of the American auto industry and the economic chaos that this brought to Detroit’s doorstep, Ms. Mae’s community has remained vibrant for much of the fifty-plus years she has resided there. Today, however, her neighborhood — once full of conversation partners, warmth, and verve — has become desolate. There are now twice as many vacant lots overgrown with brush as occupied homes. An outside observer might reasonably come to the conclusion that a devastating fire visited the block, or a capricious tornado tore away some homes and left others standing. But the blight that has eviscerated Ms. Mae’s neighborhood, and indeed much of Detroit, is a man-made disaster, one with a surprising cause: illegally inflated property taxes.

One study found that between 2009 and 2015, the City of Detroit inflated the market value of 53 to 84 percent of its homes, violating the Michigan Constitution’s rules for calculating property taxes. Additionally, a Detroit News investigation found that between 2010 and 2016, the City of Detroit overtaxed homeowners by at least $600 million. And of the 63,000 Detroit homes with delinquent tax debt in 2019, the City overtaxed about 90 percent of them. Systematic overtaxation has caused an enormous transfer of wealth from homeowners in this majority-Black city to government coffers.

Though the City of Detroit overvalued Ms. Mae’s home for years and her low income qualified her for an exemption from paying property taxes altogether, Ms. Mae had no way of knowing these things. Nowhere on the official property tax notice mailed to homeowners does it tell them how to determine the market value the City has assigned to their home. The City also did not advertise the exemption, and even when low-income homeowners did find out about it, the City blocked access by erecting unnecessary barriers.

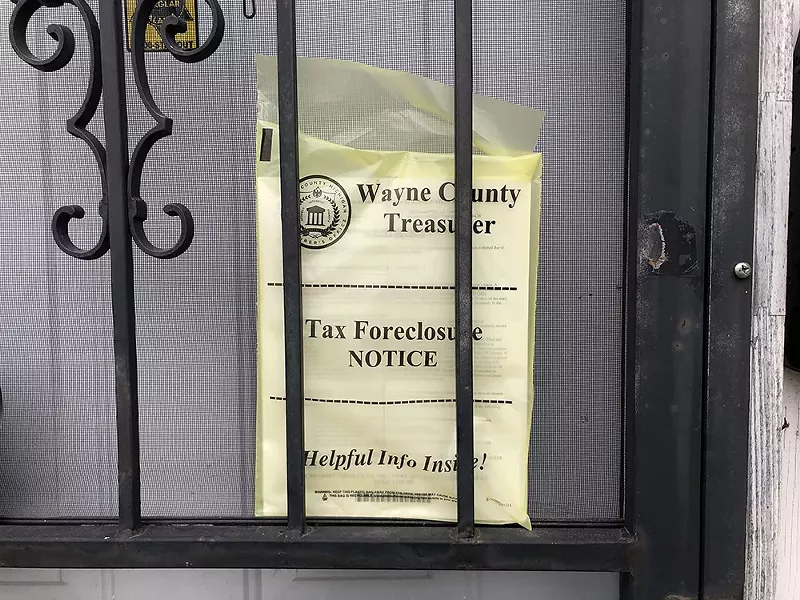

It is then no surprise that Ms. Mae and thousands of other cash-strapped residents could not pay their property taxes. Three years after a homeowner fails to pay off all property taxes, fines, fees, and interest for any particular year, the County places the dreaded yellow bag on their door, announcing the home’s impending tax foreclosure to all passersby. Ms. Mae had not paid her 2018 property tax debt, so she had a yellow bag attached to her door in 2020, warning that she was in danger of tax foreclosure in 2021. Seeing it, she prayed, “Lord, don’t make me lose my house.” Ms. Mae then said, “I hurried up and snatched it off so didn’t nobody see it because I didn’t want them to know I hadn’t paid my taxes. Then, as I looked down the street, everybody had them on their houses. It made me feel a little relieved, but I still had to pay my taxes some kind of way.”

Since unfairly calculated property taxes disproportionately affect Detroit’s most depressed neighborhoods, yellow bags dangling on these doors in October have become as common as Christmas lights hanging from roofs in December. Detroit has had more property tax foreclosures than any other American city since the Great Depression. As of 2009, the local government has confiscated one in three homes, robbing over a hundred thousand families of wealth, stability, and the relationships they have developed with neighbors over decades. Detroit’s number of Black homeowners in 1970 was 41 percent above the national rate, but today the local government is robbing residents of the wealth their predecessors fought hard to acquire and pass down. This exacerbates the already-severe racial wealth gap: in 2022, the median white family held $285,000 in wealth, and this number was $61,600 for Hispanic families, and only $44,900 for Black families.

Ms. Mae’s experience exemplifies this trend. To become homeowners, her parents, Sam and Ida Jackson, had to sidestep several pitfalls that commonly prevented Blacks from purchasing homes in the twentieth century. Now, in the twenty-first century, property tax injustice threatens to rob Ms. Mae of her shingled legacy.

The Jackson family’s homeownership journey began when Sam and Ida, childhood sweethearts from rural Georgia, wed as teenagers in 1930. Because Sam’s uncle and granduncle had both education and land, white vigilantes murdered them for being uppity and not knowing their place, hanging them in their front yard to send a ruthless message to other Blacks. With the compliance of religious, political, and other societal leaders, whites lynched about thirty-five hundred Blacks in the United States between 1895 and 1968. Because Southern whites routinely lynched Blacks for defying their subordinate position in society, and afterward sat down for dinner with their families, praying over their food, in 1937, Sam gathered his bride; his only brother, Johnny; and his family and drove to Detroit, never looking back. The Jackson family joined millions of other African Americans escaping the South’s racial terrorism to head North, hoping to secure dignity and lucrative jobs in Detroit’s auto industry.

To accommodate their thirteen-person extended family, the brothers rented a three-bedroom house on Brewster Street in a bustling Black community known as the Hastings Street neighborhood. “That’s where all the happening was at. The prostitutes, the pimps, the shows,” Ms. Mae said. “You had the colored grocery store, the Dave and Ms. Queen grocery store. You had Louie’s grocery store. You had a shoeshine shop on the corner. Then Victor’s had the clothing store. We had the movie theater. We had the bars. We had a skating rink up over the grocery store. We had Brewster Recreation Center there with a swimming pool and the best women basketball champions that came out of it.” As the memories overtook her, Ms. Mae paused for a long moment. “It was nice.”

Despite the fact that Hastings Street was a neighborhood rich in social cohesion, a place where people looked out for one another and neighbors became chosen family, outsiders viewed it as a slum. This was because both the federal government and financial institutions designated these Black communities as high credit risks, drawing red lines around them on their official maps. This process, later known as redlining, prevented the inflow of financial services like mortgages, insurance, and home improvement loans. Without the funds to invest in upkeep, dilapidated buildings and other squalid conditions inevitably resulted.

But for Ms. Mae, Hastings Street was not a slum. It was home. It was the place where she grew up, attended school, found her first love, and experienced her first heartbreak when he left her for another woman. While Ms. Mae was nursing her broken heart, Walter, the next-door neighbor with two grown children, began courting her. They fell in love. After six months of dating, they married, and because Walter was forty-five years old and Ms. Mae was only nineteen, Sam and Ida were furious when they found out.

“They didn’t like him cause he was nasty talking. He ain’t have no respect for nobody. What come up, come out,” Ms. Mae described. “They knew him from years back, from on the streets. He called himself being half pimp.” After a long pause, she continued, “Yeah, he was a humdinger.”

Before the nuptials, local authorities announced their urban renewal program, which would bulldoze the Hastings Street community to construct the Interstate 75 Chrysler Expressway. By the time construction finished in 1964, the Hastings Street neighborhood — with all its valuable, time-worn relationships, social capital, and dynamic businesses — had vanished. Blacks relocated to homes and apartments in the inner-city neighborhoods that whites were fleeing. Suburban communities were off-limits due to racial covenants: legal agreements created by homeowners and developers that prohibited Blacks from occupying certain homes.

“Everybody had to move, and so they found this house I am in now out here on Devine Street in 1965 and paid nine thousand five hundred dollars for it,” Ms. Mae explained. “My father always had a new car, but this was the first time they bought a house.” The house, built in 1923 on the City’s east side, was a one-and-a-half-story bungalow covered in white wood shingles, with four bedrooms, two full bathrooms, and one half bathroom. The home’s most prized features were its capacious porch, which extended the entire length of the home, and the enclosed garage, where Sam parked his treasured Buick Wildcat, a two-door gray beauty.

Like Sam, most of the breadwinners on his new street worked in the auto industry. Although Blacks and whites worked side by side on assembly lines, it was uncommon for them to live next door to each other, so Ida and Sam were only the second Black family on the block. “Mr. Fred and Ms. Fanny, they were the Italians next door. Mary and Bill across the street, they was hillbillies. Mr. Summa and them, they was Italian,” Ms. Mae remembered. “They were all white, but they were different denominations of countries.” There was never racial tension between the Black newcomers and white old-timers on the block. Everyone got along swimmingly.

Nevertheless, when more Black homeowners started buying in the neighborhood, real estate agents and other intermediaries began convincing white homeowners that the arrival of their Black neighbors would tank their home values in a phenomenon called blockbusting. This prompted the white families to sell quickly and at fire-sale prices. The intermediaries then sold those homes to Blacks at a significant markup, securing morally questionable profits. As a result, although the Jacksons were only the second Black family on the block, within five years, there was only one white family left.

Detroit’s 1967 Uprising — one of twentieth-century America’s largest civil disturbances — caused many remaining white home and business owners to desert the city, further depleting the tax base and economically crippling neighborhoods. “Me and my husband were living on Parker when the riot started. They was tearing up everything,” Ms. Mae said. “We went home and we was there for about four, five days ’cause we couldn’t get out ’cause of the national guard and everybody was riding through the streets with their guns and on the army trucks.”

Although whites decamped to the suburbs, Ida and Sam stayed. “They stayed because, at the time, they didn’t have no place to go,” Ms. Mae said. Blacks had very limited housing mobility, so Devine Street became Ms. Mae and her family’s permanent home. “That house means everything to me ’cause my parents bought it for me. They bought it for them, but it was for me because they knew I had to have somewhere to live because my husband wasn’t nothing,” Ms. Mae said. “He was one of them husbands didn’t want to work. He wasn’t paying no bills. He wanted the woman to work to take care of him.”

Five years after purchasing the Devine Street home, Sam died in a car crash. Ms. Mae and her husband left their apartment and moved into the home to care for Ida, whose grief over her husband’s recent death was exacerbating her existing heart condition. Since Ida’s health was quickly deteriorating, she began to worry about how her children would fare if she died. To give them added security, she tried to pay off the home loan, giving the lender, Auer Mortgage, $5,000 in cash, about half of what they had paid for the home five years earlier. Surprisingly, the company told Ida that her bulk payment covered only the mortgage interest and not the principal. Even though Ida knew that this did not make sense, she did not have the resources or specialized knowledge to fight the mortgage company.

Four short months after Ms. Mae and Walter moved in, Ida literally died of a broken heart. Ms. Mae and her cousin Jasper inherited the home on Devine Street. After paying $97 per month, in 1974, they finished paying off the mortgage. Ms. Mae and Jasper did not know that in 1976, the National Bank of Royal Oak filed suit against David Auer, the owner of Auer Mortgage, for mismanaging mortgages that the bank had contracted his company to service. Then, in 1983, Michigan’s attorney general, Frank Kelley, filed a consumer protection lawsuit against Auer Mortgage and a group of other firms. Months later, Auer was found stuffed in the trunk of his Mercedes-Benz, forcing Kelley to drop the investigation. Word on the street was that Auer’s shady dealings had finally caught up with him. Since Auer’s victims never had their day in court, Ms. Mae never even knew about any of this.

Although they were forced to pay off a predatory mortgage loan, Ms. Mae and Jasper owned their inheritance free and clear. But with Walter in the house, they did not feel free. He beat Ms. Mae relentlessly, drew a gun on Jasper, and threatened to burn down the house with both Ms. Mae and Jasper inside. Of all the abuse, Ms. Mae most vividly remembered how Walter humiliated her the night he took her to an Emanuel Laskey concert on the city’s west side.

Laskey, who was born in 1945 like Ms. Mae, was an African American soul singer known for his 1977 song whose plaintive chorus declared: “I’d rather leave on my feet than live on my knees, darling. I’d rather leave on my feet than continue to live on my knees.”

The lyrics struck a chord with Ms. Mae, describing her bitter marriage better than she could with her own words. Basking in the moment, she began swaying, laughing, and singing along. “I said, ‘Sing Emanuel, sing.’ Next thing I know I got hit upside the head. I couldn’t even enjoy a concert. He said, ‘You don’t be laughing and telling no other goddamn nigga to sing and dance in front of me.’” Walter did not allow Ms. Mae to have even simple joys. She was living in hell.

In 1986, after twenty-four years of marriage, Walter was shot to death. “I did it,” Ms. Mae soberly explained. “He came home and tried to jump on me. I was sitting there watching TV, and he pulled his shotgun to shoot me, and so I got it, and I shot him.” Deflated, she added, “It was either him or me.” In the following weeks, Ms. Mae stood trial for the murder of her husband.

Ms. Mae could only afford a neophyte lawyer, with her case being just the second of his entire career. To finance her defense, she took a $10,000 lien on her home. After a short trial, the jury acquitted her of all charges. It was not, however, until ten years later that she was able to pay off her legal debt and remove the lien.

Walter’s death gave Ms. Mae a new lease on life. But lurking around the corner, waiting to pounce on her, were new tragedies. In 1994, she injured her shoulder while lifting a patient at the nursing home where she worked. Even after the doctors completed major surgery, Ms. Mae still did not have full use of her shoulder. To make matters worse, the following year, when her shoulder was still in a sling, Ms. Mae went down to drain her flooded basement, slipped, and injured her spine. She would never work again.

With scant income, there was no money for the home repairs that the Devine Street home sorely needed. “My roof got holes. My kitchen and bathroom ceiling is leaking. It’s coming down in there. The ceiling fell in the basement from the roof leaking,” she explained. “When the flood came, it messed up my basement, my washer and dryer, and the furnace, and the hot water tank. Now I don’t have hot water. I have to boil it.”

This type of structural deterioration was not affecting Ms. Mae alone. It was happening to homes up and down Devine Street because, for decades, redlining deprived homeowners of access to home repair loans and other capital. Then, during the Great Recession, predatory mortgage loans and the accompanying mortgage foreclosure crisis decreased home values in these same redlined areas even further. Consequently, the cost of home repairs often exceeded the home’s value, leaving these homeowners’ children and grandchildren to inherit money pits instead of assets, further undermining intergenerational wealth. After a cost-benefit analysis, many walked away from their ramshackle patrimonies.

As Devine Street has declined, there has been a dramatic rise in the number of vacant, unmowed lots with grass as tall as trees. Although Ms. Mae lives in the middle of the city, it feels more like a forest, and the wild rooster patrolling the neighborhood is proof positive. Several neighbors had complained that this feathered stud was gallivanting through the streets, crowing at full volume in the early-morning hours, climbing and scratching cars with its sharp claws, running through their yards, and wreaking general havoc.

Although Devine Street has transitioned from a bustling area full of people to a desolate place where roosters roam, in 2023 the City of Detroit taxed Ms. Mae’s home as if it were worth $31,200, an amount far higher than it could ever sell for on the open market.

What’s worse is that Ms. Mae’s parents purchased the home in 1965 for $9,500, which, adjusted for inflation, is about $92,500 in 2023 dollars. Instead of increasing, her home’s value decreased. Under normal circumstances, over time, ownership creates wealth because the market value of a home rises and the equity also rises as homeowners pay off their mortgage. Homeowners can pass this wealth to subsequent generations, who gain an advantage when they combine these inheritances with money they are able to generate on their own. This is not how it turned out for Ms. Mae and her neighbors, however.

This is in stark contrast to the suburban communities where Mr. Fred, Ms. Fannie, Mr. Summa, and the other whites who once lived on Devine Street fled in the 1960s. In 2020, the median home value in Grosse Pointe was between $300,000 and $399,999; in Livonia it was between $200,000 and $249,999; in Dearborn it was between $150,000 and $174,999; and in Warren it was between $125,000 and $149,999. Detroit’s median home value, however, was only between $50,000 and $59,999. Racial covenants tucked into the deeds of suburban homes kept Blacks out, denying them the opportunity to live in homes that increased in value over the years instead of decreasing.

Ms. Mae’s story is plagued by several overlapping racist policies — more imprecisely known as structural or systemic racism — which are any written and unwritten laws and processes that produce or sustain racial inequity. While racist policies such as racial covenants, urban renewal, redlining, blockbusting, predatory mortgage lending, and, most recently, illegally inflated property tax assessments undermined Ms. Mae’s ability to accumulate assets, blame falls on the things that are most visible: the homeowners themselves. That is, due to their own “irresponsibility” or “ignorance,” homeowners are presumed culpable and thus deserving of their hardships. Therefore, the State’s role is to fix the people by providing services like financial management classes or soft-skills training. Meanwhile, racist policies, the true culprit, vanish into the background.

Using data from over eight years of research on the property tax foreclosure crisis in Detroit — including over two hundred interviews with homeowners, real estate investors, and policymakers, as well as participation in a grassroots movement for property tax justice — this book reveals and gives a name to an overlooked but widespread phenomenon: predatory governance, which is when local governments intentionally or unintentionally raise public dollars through racist policies.

Our national conversations about racism accelerated when cell phone footage captured violent images of police officers murdering Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, George Floyd, and other Black people. Plundered seeks to shift the focus of our nation’s racial justice conversation from the physical violence that state agents exert to the less conspicuous but intensely damaging bureaucratic violence that institutions routinely inflict through racist policies like those that have harmed Ms. Mae and her neighbors. The story of Devine Street, the story of Detroit, and indeed the stories of many other cities across the U.S. are, in fact, tales of predatory governance.

Whether it is targeted tickets and fines in Ferguson, abuses of civil forfeiture in Washington D.C., jailing defendants for court debts in New Orleans, or inequitable property taxation in Chicago and a slew of other cities, American cities routinely replenish public accounts by bleeding Black and brown citizens, further widening the racial wealth gap. To bring this national phenomenon to light and give voice to those affected, like Ms. Mae, Plundered unearths and dissects the racist policies undergirding Detroit’s property tax foreclosure crisis.

A book launch event for Plundered features a conversation between Atuahene and Orlando Bailey, executive director of Outlier Media set for 5-6:30 p.m. on Friday, Jan. 31 at Detroit Mercy Law School; 651 E. Jefferson Ave., Detroit. Tickets are available from eventbrite.com for $34.45 and include a copy of the book.