Downtown tax incentives are exacerbating the ‘two Detroits’ problem: report

Nearly 50 years after the Downtown Development Authority was established, the city’s downtown is thriving while schools, libraries, parks, and others are comparatively underfunded

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

Tax incentives for Dan Gilbert and other downtown Detroit developers aren’t providing promised benefits that Mayor Mike Duggan and allied business leaders said would spill over to the rest of the city’s residents, a new report finds.

That has created a situation in which the wealthiest residents are largely the beneficiaries of the city’s controversial Downtown Development Authority (DDA) district, while longtime, largely low-income and Black residents in the other neighborhoods do not receive much benefit.

Though the DDA district has increased income tax revenues citywide and fueled downtown’s growth, it has, on balance, not achieved its aim of boosting the whole city, the report’s authors conclude. They argue that the DDA should pay off its debt, then potentially be wound down.

“Downtown has had a level of vibrancy that is not present in many other parts of the city,” the report continues. “Likewise, it is clear that investments in the downtown have not lifted the city to share in any levels of prosperity.”

The report was commissioned by the Detroit City Council and aims to provide clarity around the benefit that the DDA district and Detroit Economic Growth Council provide the wider city.

The Duggan administration and developers have pointed to gleaming new buildings in downtown areas as evidence of their incentives’ success in rebuilding the city, but the report looked at broad level data that shows how Detroit’s economy has in many ways sputtered since the DDA’s 1975 implementation.

The DDA district siphons property tax revenue that would otherwise contribute to the city’s general fund, Wayne County general fund, school districts, parks, libraries, and other “taxing jurisdictions.” In 1975, downtowns were struggling and DDAs were established around the nation to divert money from other city services that were comparatively well funded.

Nearly 50 years later, downtown Detroit is thriving, while schools, the city, and libraries and other taxing jurisdictions are comparatively underfunded. In 2022 alone, the DDA captured $63 million that could have gone to other city or county services, but was instead diverted to subsidize downtown developers.

The Citizens Research Council of Michigan report looked at broad level data around housing prices, personal income, the city’s overall property value, and other measures to determine if a half-century of the DDA had lifted Detroit.

The report’s co-author, Eric Lupher, tells Metro Times the initial idea for the DDA district was to create “short-term pain” for schools, libraries, parks, and general funds in exchange “for long-term gain.”

“But here we are 47 years later and they’re not gaining anything,” Lupher adds. “We’ve lost sight of the end goal, which is to increase the tax base and benefit the whole community.”

Duggan spokesperson John Roach says the report actually states that the incentives program has helped the city, and “ultimately found that ‘[t]he city has benefited from increased income tax revenues relating to business activity downtown.’”

But the paragraph that Roach quotes also notes gains in income tax only partially offset hundreds of millions of dollars of lost property tax revenue that could have gone to providing services to the rest of the city via schools, parks, libraries, and general funds. Those have only “indirectly” benefited from the personal income tax gains, the report states.

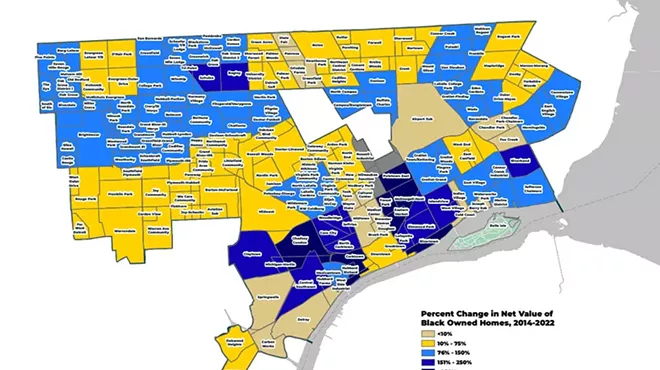

The report notes the 22.4% increase in per capita personal income for Detroit residents “masked deep racial disparities among city residents.” In short, the gains were broadly driven by largely white, wealthy people who have moved to Detroit in recent years, or who work in Detroit, but do not live here. That makes the “continuation of isolated and concentrated poverty and unemployment more likely,” the report states.

The average wage of Detroit residents is around $40,000 annually, but the average job in Detroit pays $80,000, pointing to the income tax gains being driven by people who work downtown, but do not live there. It also points to higher wages concentrating in downtown.

That amounts to “gentrification,” Lupher says.

“That’s not necessarily bad because the city needs investment and it needs people of all walks of life, and middle class and upper income people are important for building the tax base,” Lupher says. “But again all that new investment, the townhouses going up, it’s not necessarily benefiting the neighbors and longtimers that have stuck it out and are hoping for a better time.”

Meanwhile, there has not been a promised spill over into housing in recent decades. The report notes anecdotal housing successes, but broad level data shows the city’s tax revenue attributable to residential taxes dropped from 67% to 35% between its 2006 peak and 2022.

“The recent reports of gains in housing prices are encouraging, but the net gains to the city’s tax base are negligible in a historical context,” the authors wrote.

The city’s property value is also still seriously lagging even as downtown flourishes. After dropping during the white flight of the 1960s and ’70s, it rebounded between 1994 and the Great Recession, but it fell off again and has barely recovered. Detroit’s inflation-adjusted state equalized value (SEV), or value of its real estate, is still 74% below 1966 levels, though it has ticked up over the last two years.

In the face of administration fanfare over high profile downtown developments, the SEV data is “another reality check,” Lupher says.

“There are good things happening but it’s important to keep perspective — the city has fallen very far over the last five decades,” he says.

Roach called the report “deficient” because it did not include $234 million in income tax revenue growth between 2014 to 2024 as evidence of the DDA’s success.

“Mayor Duggan made it clear to the bankruptcy court in 2014 that his central strategy was to forgo property tax revenues in order to drive income tax revenues, which he predicted would be far more lucrative for the city,” Roach says. “That strategy has been remarkably successful — it’s responsible for 10 credit rating upgrades and [Detroit’s] return to an investment grade rating.”

The increased revenue helped the city combat crime, improve EMS response times, and provide affordable housing subsidies, among other benefits to longtime residents, Roach adds.

He says the report’s authors were “embarrassing” themselves by not including the full $234 million figure.

Lupher says the full $234 million cannot be attributed to the DDA because it covers the entire city, not just downtown. He adds that he made multiple requests to the Duggan administration for the portion of the $234 million that could be attributed to the DDA, but the administration would not provide it.

The administration then called the report “deficient” because the report did not include data the city withheld.

When asked why the Duggan administration did not provide the information, Roach claimed that Lupher never made the request. When presented with the date of the request, Roach did not respond to a request for comment.

The new report comes on the heels of a Detroiters for Tax Justice paper that found the city lost out on $1 billion in tax revenue via incentives during the same period.

Alejandro Navarrete, a researcher for Detroit Action, a community advocacy group, tells Metro Times CRC’s report is “evidence that highlights the lack of evidence” that benefits are spilling over to the rest of the city. It also reveals “rigidity” in cost-benefit analyses used to justify the DDA district and incentives, he adds.

“People propose a cost-benefit analysis with forecasted benefits, but when the benefits don’t materialize, we get gaslit,” Navarrete says.

Detroit isn’t unique — DDA districts around the country have failed to provide spillover benefits, says Greg LeRoy, director of Good Jobs First, which tracks corporate subsidies. He pointed to Baltimore, which faces a similar problem as Detroit.

He said a main reason DDAs fail to revitalize broader cities is the lack of strong community benefit agreements tied to downtown projects. Though Detroit has a community benefits ordinance in place, it is viewed by many community members as weak. The Duggan administration, its corporate allies, and unions in 2016 torpedoed a much stronger community benefits ordinance.

Strong guarantees that neighborhood residents will receive good paying jobs, above minimum wage, apprenticeship programs, or set asides for minority-owned businesses are essential, LeRoy said. Absent that, there are not “any kind of ripple effects that would tie the success of downtown to the success of the rest of the city and that’s the big problem here.”

What Detroit has executed is “a real estate fortress strategy, but it’s not a saving-the-city strategy,” LeRoy added.

A previous version of this article misstated the name of Gerg LeRoy. It has been corrected.