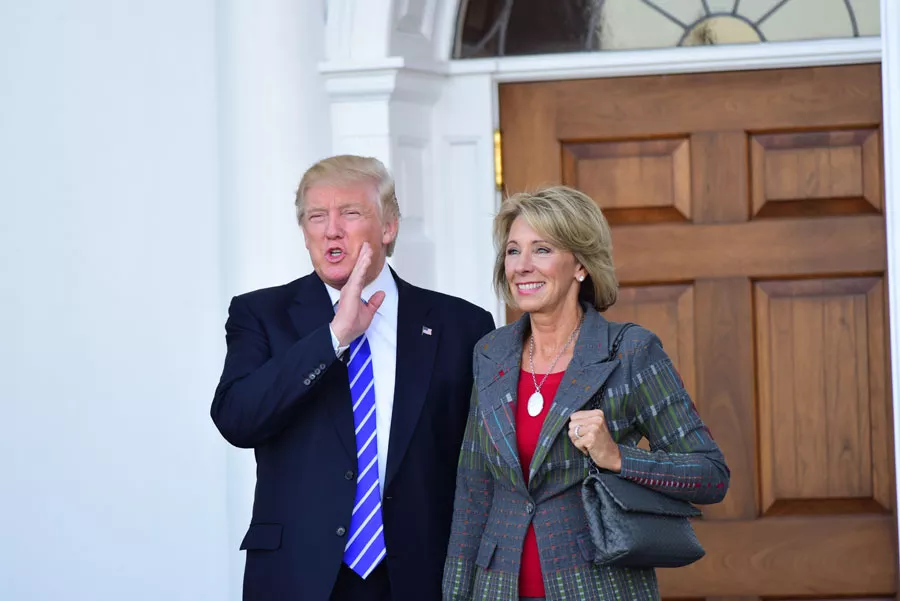

The first thing you notice about Betsy DeVos — President Donald Trump's choice to run the United States Department of Education — is that she is rich.

Actually, the word "rich" doesn't really do it justice. Cookie batter is rich. Betsy DeVos is wealthy in the way that Donald Trump wishes he was (and very well may be by the time his presidency is over).

Betsy DeVos is on another level entirely.

Begin with the family money. Before Betsy DeVos was a DeVos, she was a Prince — the daughter of Edgar Prince, to be specific. Prince père ran a successful auto parts manufacturing business in Holland, Michigan, which he had built into a billion-dollar empire by the time of his death. Prince used some of his personal wealth to bankroll what would become the organizational infrastructure of the religious right, providing vital seed money for conservative Christian advocacy groups like the Family Research Council and Focus on the Family.

Bringing about one of the largest mergers of conservative wealth, Betsy married into the DeVos family, whose patriarch — father-in-law Richard DeVos — had built a multibillion-dollar fortune as the co-founder of multilevel marketing behemoth Amway.

Taken as a whole, hers isn't merely the sort of wealth that renders one "out of touch" with the common man — it's a fortune that has shielded DeVos from anything that even remotely resembles hardship from the time she was born until now. She has had no real contact or experience with adversity of any kind. She is almost a celestial body — untouched and untrammeled by the obstacles and pitfalls that the vast majority of the American people have to navigate on a daily basis.

And for that same vast American majority, education — and all of the mobility and opportunity it offers — is the primary vehicle by which they have to surmount the myriad challenges they face. It should be a matter of great concern that the person who now oversees America's educational infrastructure has never even nominally shared in these struggles.

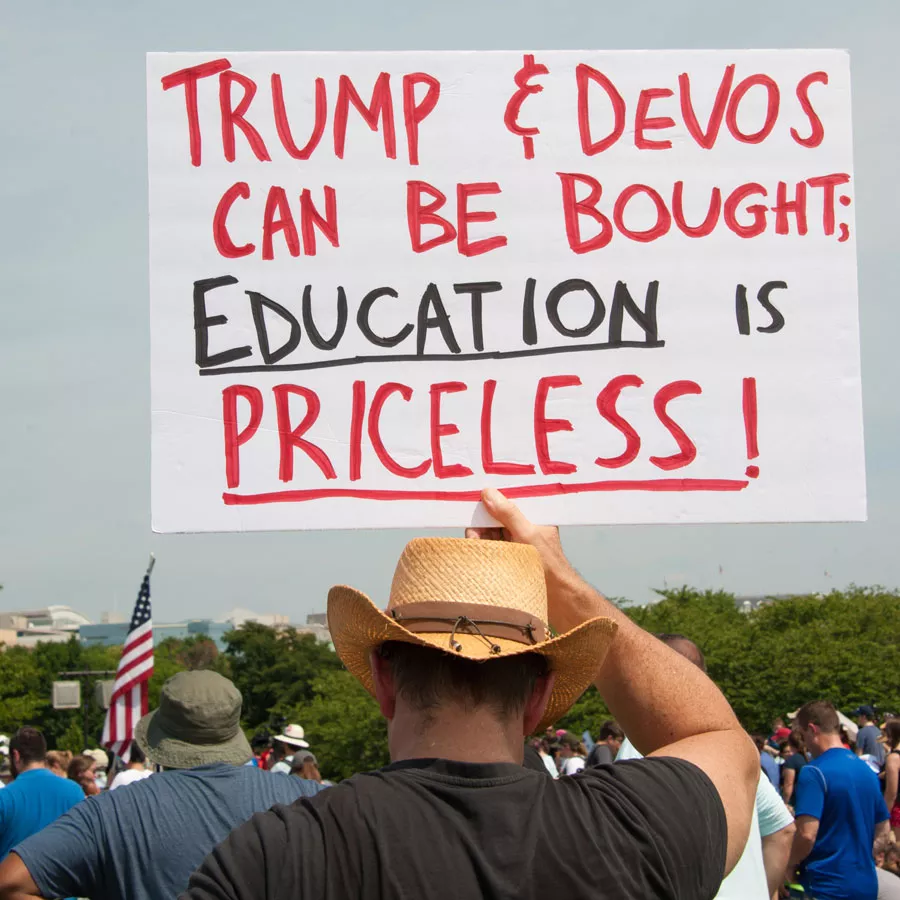

Of course, with Betsy DeVos, the educational concerns don't end there. She has long yearned to radically transform public education, dramatically increasing the number of private and religious schools that educate American children. She's called U.S. public schools a "dead end" and in 2001, she explained how her school choice advocacy is driven by a desire to "advance God's kingdom." Aside from her ideological Christian fervor, she and her family also strongly support recreating schools in a more plutocratic image, where they can reward those entrepreneurial innovators looking to make a buck. When Trump tapped her to serve as his Education Secretary the public raised a hue and cry that even caught the liberal activists in the raise-a-hue-and-cry business by surprise.

Fittingly, however, DeVos' appointment has given her an illuminating first taste of what adversity actually feels like.

From the very moment DeVos' Senate confirmation hearing kicked off on Jan. 17, 2017, there was an unmistakable sign that President Trump's newly anointed education czarina was in for a rough ride.

Republican operatives who had handled her confirmation training were watching nervously. Her lead sherpa through the process, Lauren Maddox, was a registered lobbyist with the Podesta Group — not a former lobbyist now getting back into public service, but an actual, current lobbyist paid by corporate clients for her ability to sway public policy. Maddox, a former Bush administration Education Department official, as well as a past aide to House Speaker Newt Gingrich, had the task of educating DeVos on education.

DeVos made a less than ideal student. "Her mind didn't naturally go to different places," recalled one participant in the confirmation training sessions, rather charitably. "She was a very visual person, so she had to have the stuff color coded in front of her."

That, though, presented its own problems, as the team knew that if the color-coded flashcards were visible on camera, it would be a major embarrassment, so pains were made to keep them off screen. "You don't want to have all those things out there because people can see it," the GOP official noted.

Fortunately, DeVos would get some help during her hearings from the person running the show. The Republican chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP), Lamar Alexander — himself a former U.S. Secretary of Education who'd served as the senior senator from Tennessee since 2003 — gaveled the hearing into session and immediately started setting some rather unusual ground rules, proclaiming that each committee member would be granted only five minutes to question the nominee. Alexander asserted that this was to be the hearing's "Golden Rule" — a precedent he claimed had been firmly established by past confirmation hearings including those of President Barack Obama's nominees for the Education Department.

It was not, as Democratic ranking member Patty Murray made clear, a precedent with which anyone on the committee had hitherto been familiar. And despite Alexander's repeated protests that it was, in fact, "as clear a precedent as I could think of," it led to every Democrat on the panel accusing Alexander of working to shield DeVos from their scrutiny.

Of course, Democrats' demand for additional questioning time was driven by another precedent: None of the previous nominees being held out by Alexander as examples were quite so burdened with ethical quandaries. Indeed, DeVos' hearing had, at this point, already been postponed due to her failure to complete her required review with the U.S. Office of Government Ethics, a failure which only primed the pump for increased suspicion and a wider inquiry.

And beyond that, DeVos had, by this point, a long, well-documented history of antipathy toward America's public schools — a veritable feast for anyone with the moxie to hold her to account.

So it's not hard to see why Democrats entered the hearing ready to dig down into DeVos' murky history and her ideological beliefs, or why Alexander would want to use the convenience of his HELP committee chairmanship to throw up as many procedural barricades as he could. The goal for Alexander was to shelter the billionaire heiress from tough questioning. The goal for DeVos was not to create any viral videos.

As it would turn out, however, Alexander's efforts proved insufficient. Really, nothing short of canceling the hearing entirely would have helped DeVos avoid exposing the fact that for someone with such strongly held opinions about education, she knew precious little about education.

In fact, one of the most widely puzzled-over answers that DeVos gave during her confirmation hearing was in response to a very direct question, posed by then-Minnesota Senator Al Franken. When Franken started in on his line of inquiry, he began by asking her a seemingly softball question regarding the appropriate way to use standardized tests. "I would like your views," he asked DeVos, "on the relative advantage of doing assessments and using them to measure proficiency, or to measure growth."

It was, without a doubt, a wonky question — the sort that would likely not have been familiar to anyone outside of the education industry. But in terms of beginning a line of inquiry, this was a rather innocuous place to start. Growth versus proficiency is not considered an obscure education policy debate, but a rather fundamental one. Those who are concerned with "proficiency" favor measuring whether children are achieving certain education milestones in a timely fashion, like the ability to read at grade level. Those who take up the "growth" side of the debate would prefer that testing account for whether children are making sufficient progress over the course of a school year.

In asking the question, Franken was simply trying to establish a benchmark with DeVos, a way to better assess her overall views on school accountability. He could not have possibly expected the answer he got.

"I think if I am understanding your question correctly around proficiency," said DeVos, "I would also correlate it to competency and mastery, so each student is measured according to the advancement they are making in each subject area."

"That's growth, that's not proficiency," interrupted Franken. "I'm talking about the debate between proficiency and growth, and what your thoughts are."

A gaffe in Washington is famously said to occur when a politician speaks the truth accidentally. This was a different sort of gaffe, an accidental revelation of a stunning level of ignorance. It turned out she had no thoughts on the question.

Elsewhere, at least, she had vague thoughts. When Senator Murray asked DeVos whether or not she would commit herself to neither working to privatize public schools, nor cutting "a single penny for public education," DeVos simply gave a boilerplate answer about how she looked forward to "working with you to talk about how to address the needs of all parents and students ... to find common ground in ways we can solve those issues and empower parents to make choices on behalf of their children that are right for them."

"I take that as not being willing to commit to not privatize public schools," responded Murray.

When it was Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren's turn to question the nominee, Warren turned her attention to for-profit universities and the Education Department's role in policing such entities. Warren asked DeVos how she would go about protecting students from being scammed. When DeVos answered that she would be "vigilant," it wasn't enough for Warren, who wanted to know how, exactly, she'd set about ensuring that predatory fraudsters would not victimize students. DeVos did not seem to grasp that there were tools, like gainful employment regulations, already at her disposal to aid in this fight. And once DeVos was informed of her options, she refused to commit to using them, instead telling Warren that she would "review" those regulations.

The word ‘incompetent’ gets overused in Washington, but for many it was a term that aptly described Betsy DeVos.

tweet this

"I don't understand about reviewing it," said a perplexed Warren. "We talked about this in my office. There are already rules in place to stop waste, fraud and abuse. ... Swindlers and crooks are out there doing back flips when they hear an answer like this."

And yes, there was that moment when DeVos, attempting to explain why it was sensible for "locales and states to decide" whether or not guns belong in public schools, cited the need for teachers to have "a gun in the school to protect from potential grizzlies." Never let it be said that DeVos couldn't serve up a much-needed viral headline to the media.

The word "incompetent" gets overused in Washington, but for many — judging, perhaps, a little too prematurely — it was a term that aptly described Betsy DeVos. Her confirmation hearing, it must be said, went a long way toward reinforcing that perception, revealing a nominee who often seemed as woefully adrift on the basics of education as she was certain that she knew the best possible way to oversee it.

And so, Congress' phone banks heaved and cracked under the volume of calls, beseeching her swift dismissal. Two Republican senators, Alaska's Lisa Murkowski and Maine's Susan Collins, stunned at the opposition pouring through their phone lines, took heed and announced that they would be withholding their support for her nomination, while several others wavered.

Losing those two votes forced the Trump administration to hustle Vice President Mike Pence up to Capitol Hill to cast the tie-breaking vote on a Senate confirmation, something that had previously never been required. DeVos had made it, by the thinnest of margins — the first Secretary of Education ever confirmed without bipartisan support. Pence would refer to casting the deciding vote — a ritual humiliation for any administration — as a "high honor."

But it was Collins and Murkowski who should be credited for doing the honorable thing — looking past the ideological ambitions of their party in order to consider the needs of their own constituents. For both women, DeVos' devotion to charters and school vouchers posed a real threat, as their states feature far-flung communities for whom public school is the only available option. Choice is merely a word when there's only one school within miles and miles.

"I think that Mrs. DeVos has much to learn about our nation's public schools, how they work, and the challenges they face," said Murkowski in a speech on the Senate floor. "And I have serious concerns about a nominee to be secretary of education who has been so involved on one side of the equation, so immersed in the push for vouchers, that she may be unaware of what actually is successful within the public schools and also what is broken and how to fix them."

In this limited respect, Murkowski really had DeVos pegged. But even Murkowski failed to appreciate the extent of the nominee's inadequacies, because despite being "immersed in the push for vouchers," DeVos arrived in Washington with such a spotty record of both advocating for and implementing her grand designs, that even her fellow travelers in the voucher and charter movement — a community of ersatz thought leaders who'd normally not think twice about redirecting public money to private-sector schemes or disemboweling a teachers' union — were hesitant, if not wholly averse, to supporting her nomination.

For example, while New York magazine politics writer Jonathan Chait — who frequently bedevils liberals for his unalloyed support for charter schools — didn't find DeVos to be Trump's most objectionable nominee, he nevertheless proclaimed his opposition to DeVos on the grounds that she was an incapable avatar of the charter school movement. "It's important to understand what is actually concerning about DeVos," Chait wrote. "In addition to lacking policy heft, she is in the grip of simplistic ideas about education and she sees parental choice as a panacea. If parents can choose which school to send their children to, she believes, competition will inevitably force improvement. From the standpoint of center-left education reforms, this is dangerously simplistic."

Chait, noting that charter school performance varies widely across the country, targeted Michigan's charter system — which DeVos had a strong hand in shaping — for its lack of sufficient oversight and its utterly dismal nationwide ranking.

Michigan State Board of Education President John Austin, who is also a strong supporter of charter schools, concurred, telling Politico: "The bottom line should be, 'Are kids achieving better or worse because of this expansion of choice?'" His state's policies, Austin said, were "destroying learning outcomes." "The DeVoses were a principal agent of that," he asserted.

It's easy to paint a fretful portrait of DeVos. Her track record as a reformer, coupled with her consistent inability to account for the most basic educational concepts, is enough to leave anyone with the firm impression that she simply does not know what she's doing.

But to borrow from Marco Rubio, a supporter of DeVos, "let's dispel once and for all with this fiction" that Betsy DeVos doesn't know what she's doing.

She knows exactly what she's doing.

A year after her shaky hearings, the limitations Democrats faced digging into her past paid dividends for DeVos, her family, and one of her favored corporations. On Jan. 12, it was announced that a company named Performant Financial Corp. would receive one of two lucrative contracts, enabling it to assist the Department of Education in collecting overdue student loans.

The announcement was a boon to Performant, who had spent a year locked out of the Department of Education's lucrative contracts. But perhaps more importantly it would provide a tidy boost to the DeVos family's bottom line.

Among the many financial entanglements DeVos brought with her to Washington, one was a DeVos family investment company named RDV Corporation. RDV was, in turn, tied to the Delaware-based company LMF WF Portfolio I LLC. And that confusing series of letters from Delaware was a financial backer of Performant.

Prior to DeVos being tapped as Secretary of Education, this was good business for the family fortune — the loan servicing company had already received millions of dollars in past Department of Education loan servicing contracts. Every time the company collected on a loan, they took home a commission from the Department of Education. Those commissions provided a little bit of profitable cream for the DeVos family's investment portfolio — trickle-down economics in the truest sense of the word.

It was a pretty good trickle at that. Performant's 2016 financial report noted that the company had "provided recovery services on approximately $8.6 billion of combined student loans and other delinquent federal and state receivables," including the skip-tracing of defaulted lenders, wage garnishment, and "litigation services."

Prior to DeVos being tapped as Secretary of Education, student loan collection was good business for the family fortune.

tweet this

According to a January 2017 Bloomberg report, Performant had a "total revenue of $148.7 million in its most recently reported four quarters," ending in October of 2016. And this money was all coming in at a time when Performant had to compete for Department of Education business amid a sizable field of firms awarded similar contracts.

Along the way, however, Performant managed to rack up 346 customer complaints with the Better Business Bureau, as well as a healthy share of customer complaints to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. It's perhaps not that surprising that in December of 2016, Performant was excluded from a new contract with the Department of Education — a move that sent Performant's share value down "43 percent in one day," according to Bloomberg.

This all meant that a not-insignificant portion of the DeVos family fortune, knit up in the profits taken by a loan-servicing scofflaw, was lost a few weeks before Trump's inauguration.

Of course the moment DeVos was picked to be Trump's nominee, it triggered a series of mandatory divestitures, in keeping with the guidance offered by the Office of Government Ethics. From an ethical standpoint, such divestments were necessary to prevent potential Cabinet members like DeVos from feathering their own nest with the largesse that lucrative government contracts offered.

Greg McNeilly, a spokesperson for DeVos, told Bloomberg that she and her husband would, indeed, rid herself of her stake in Performant. However, he did take pains to mention that this would not "obligate other family members or RDV itself to divest" from Performant.

Performant's performance thus still had a role to play in the DeVos family's bankrolls. That puts the steps that the Education Department under DeVos took next in a new light.

DeVos began by defanging the government watchdogs who had traditionally policed the student loan beat, dogging companies like Performant for their failures to properly assist their customers. On April 11, DeVos formally withdrew two memos issued by the Obama administration that offered guidance to the Federal Student Aid office — responsible for servicing over $1 billion in student loans — on how to provide better service to borrowers who wanted to manage, or even discharge, their student debt. For the Obama administration it was a late-in-arriving but vital course correction for the agency, which had hitherto acted mainly in the interest of maximizing repayment proceeds.

The Obama administration rightly faced tremendous pressure to tame the unruly world of student loan servicing, and make things fairer and more equitable for borrowers. Notably, there was a great need to get the Department of Education more fully involved in protecting consumers. As the Nation's David Dayen reported, the Department's "own inspector general found in 2014 that the department didn't even track borrower complaints, let alone engage in actual oversight."

Much of the work being done to assist borrowers was conducted by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Government Accountability Office, which found the world of student loan servicing to be an Augean Stable of cheats and mismanagement. As the Washington Post's Danielle Douglas-Gabriel reported in April of 2017, the CFPB had documented numerous "instances of servicing companies providing inconsistent information, misplacing paperwork, or charging unexpected fees." And GAO researchers found that 70 percent of borrowers who had ended up in default would have qualified for lower monthly payment options that would have kept them in good graces — had loan servicers bothered to provide them with the necessary information.

By the end of the Obama administration, the CFPB had emerged as one of the more dogged cops on the student loan beat. Their efforts were bolstered by an information-sharing arrangement with the Department of Education, which the CFPB used to research and rein in loan-servicer scofflaws. In August of 2017, the head of the Department's Financial Student Aid agency, A. Wayne Johnson, sent a letter to then-CFPB head Richard Cordray, terminating this information-sharing arrangement.

According to Johnson — who prior to being hired by DeVos was the CEO and founder of a private student loan company named Reunion Financial Services — the ostensible rationale for ending this interagency partnership was a complaint that the CFPB had "violated the intent" of the arrangement by failing to direct Title IV federal student loan complaints to the Department of Education in a timely enough fashion, and for expanding the CFPB's "jurisdiction into areas that Congress never envisioned," in reference to the consumer protection agency's lawsuit against Navient, another bad actor in the student loan collection wilderness.

Johnson's letter sprinkled a little creatine all over Wall Street. As Bloomberg's Shahien Nasiripour reported, Compass Point research director Michael Tarkan immediately recommended that his clients invest in loan servicing companies. Tarkan said that the Department of Education's was an "unambiguous signal" that the Trump administration (and DeVos) was going to be much more accommodating to student loan companies in terms of oversight and scrutiny.

But that would hardly be the only way DeVos would work to Performant's benefit. Not only will this new contract bring the company back into the Department of Education's loan servicer fold after a year of having been cut out entirely, they will be one of only two companies cut in on Department of Education's student loan portfolio. In the past, the Department has contracted with as many as 17 firms to perform student loan collection, and as The Washington Post noted, "Attempts to whittle down the number of firms have been met with resistance."

Two years ago, when only seven companies were selected to manage the portfolio, it touched off considerable protestations among those companies that were left out of the process — the January 2018 decision to select new contractors was supposed to resolve this conflict. But DeVos' Department of Education has, perhaps, only re-inflamed this controversy by reducing the field even further: Performant is joined by only one other firm, Windham Professionals, in servicing loan contracts worth an estimated $400 million.

Windham, at the very least, deserved to be dealt in. Back when the field of servicers was reduced to seven firms, protests from the companies that were left out — including Performant — forced the Government Accountability Office to undertake a thorough evaluation of all the companies that had submitted bids. According to the GAO's subsequent report, Windham held up quite well in the crowded field, earning an "exceptional" rating for past performance and a "satisfactory" rating for management. Performant, by contrast, did not fare as well — they only rated "satisfactory" in terms of past performance, and "marginal" on management.

Performant's resurrection has raised eyebrows. As Todd Canni, an attorney for one of the bidders that lost out in the process, told The Washington Post, "It simply does not make sense that the agency would choose to work with lower-rated [companies] with marginal ratings that do not have an exceptional past performance record." Indeed, going just by the GAO's evaluation, there were six other firms besides Windham that rated higher than Performant in the categories of past performance and overall management.

Performant's good news sent their stock price skyrocketing. Meanwhile, spokespersons for everyone involved stepped forward to say the required pleasantries. A Department of Education flack ensured reporters that DeVos had "no knowledge, let alone involvement" in the decision to award Performant the new contract. Richard Zubek, Performant's head of investor relations, followed suit by insisting that no one from the firm "had any direct or indirect contact with Secretary DeVos or anyone related to Mrs. DeVos."

But given Performant's checkered history and mediocre ratings, as well as the existence of substantially higher-rated options among the many companies that had performed loan collection work for the Department of Education, it's difficult to fathom what particular quality allowed Performant to surge back to prominence in the eyes of the Department of Education and to be cut in on more profitable terms this time around. As Canni told The Washington Post, "It is beyond dispute that the [Education Department's] decisions have, at a minimum, created the appearance of a conflict of interest," adding, "Given the fact that Performant was not a highly rated [company] and, in fact, was rated fairly low ... the agency will be under intense scrutiny and will need to explain how suddenly these ratings changed so significantly to allow Performant to leapfrog over so many" more deserving firms.

Of course, with the CFPB sidelined, it's not clear from whence this scrutiny will come. What is clear is that the decision is, in any event, going to be good for the DeVos family's business — providing seed money to Republican office-seekers and the infrastructure of the conservative movement.

Reprinted from School House Wreck: The Betsy DeVos Story with permission from publisher Strong Arm Press. The book is available at strongarmpress.com.