Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard - Inline - Content",

"component": "35519556",

"insertPoint": "5th",

"startingPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "3",

"maxInsertions": 100,

"adList": [

{

"adPreset": "LeaderboardInline"

}

]

}

]

A suspect in a blurry photo was accused of shooting a 34-year-old man following an argument on Detroit's east side in November. With no other leads, most police departments would have sent the photo to the media and hoped someone recognized the suspect.

But Detroit has another tool in its crime-fighting arsenal — a controversial, $1 million system that uses facial recognition technology.

Using a screenshot from surveillance video, police scanned the image of the suspect and waited for the software to produce matches from a database of mug shots, driver's licenses, the Michigan Sex Offender Registry, and other photos.

The first three matches turned out to be wrong. But the fourth appeared to be a breakthrough. With a name to match the face, police searched social media and found the suspect's Facebook page, where the man had posted a photo of himself wearing the same sweatshirt he had on in the surveillance image. In another photo was the same getaway car caught on video.

The photos were enough to convince prosecutors to issue an arrest warrant for 22-year-old Davevion Dawson on charges of assault with a deadly weapon and carrying a concealed weapon. Police are still looking for him.

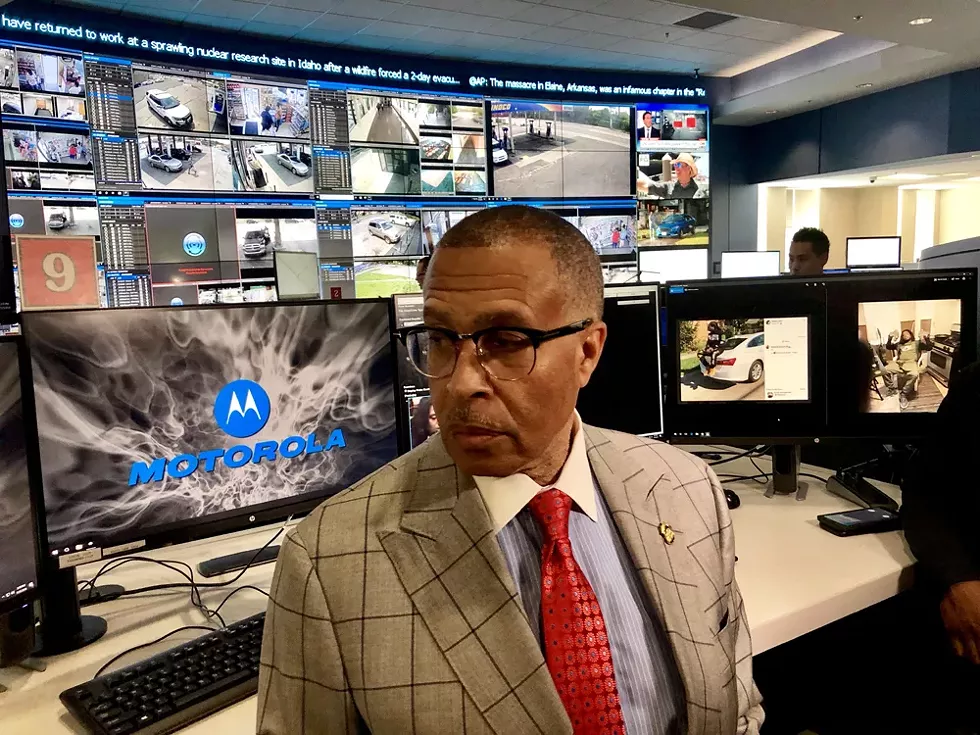

"Now we're feeling good about the identification," Detroit Police Chief James Craig says, showing a half dozen reporters how the system works after he and his department were criticized for quietly using the software without so much as a public hearing.

Civil liberty advocates say most facial recognition matches aren't as clear cut as the chief's example. Without the Facebook photos to confirm the suspect's identity, police would have no other leads and no way of knowing the first three matches were wrong, which could lead to a false arrest or innocent people caught in court trying to prove they aren't guilty.

"You cannot rely on the software by itself," Craig admits. "It's a lead only. We can't arrest solely on this."

Detroit's use of the technology has come under intense scrutiny since May following a Metro Times story about a recent study by Georgetown Law's Center on Privacy & Technology, which sounded the alarm on the city's extensive surveillance network and facial recognition software. Police had been using the face-scanning system for nearly two years without public input or a policy approved by the Detroit Board of Police Commissioners.

Over the next two months, protests broke out, town halls were held, and residents have called for a ban, citing increasing evidence that the technology is error-prone and an affront to privacy rights. The technology has been found to be the most prone to error when it comes to recognizing people with darker skin — a major issue in a city that is nearly 83 percent Black. Critics say the technology violates people's civil rights because it's used without a warrant.

"The technology is flawed in many ways," Rodd Monts, ACLU of Michigan's campaign outreach coordinator, tells Metro Times. "To put a technology in place in a city of color that is already over-policed just opens the door for a host of problems that could likely get people caught in the system who shouldn't be."

Now the city of Detroit, Michigan lawmakers, and Congress are considering banning facial recognition technology.

On Monday, state Rep. Isaac Robinson, who introduced a five-year moratorium on the technology, hosted a town hall at the historic King Solomon Baptist Church on Detroit's west side. A bipartisan panel warned about 30 people in attendance that the technology is racially biased and could lead to innocent people being imprisoned.

"Government seems to be trending more and more towards biometrics — which is using your body as your ID — so the more facial recognition technology that we get into and the more they're storing our data, the more opportunity there is for our personal information to get hacked as we go further and further down this road," David Dudenhoefer, chairman of the 13th Congressional Republican District Committee and one of the panelists, tells Metro Times before town hall begins. "It's not so much the concerns that I have about the current administration or the current body of police commissioners that are discussing this. It's 20 years down the road when a future administration, a future body of police commissioners, or city council reaches the conclusion that what they've done with this technology doesn't go far enough and they want to go a few steps further."

How the technology works

Detroit's facial recognition software is especially pervasive because it's used on a quickly expanding surveillance network of high-definition cameras under Mayor Mike Duggan's Project Green Light, a crime-fighting initiative that began in 2016 at gas stations and fast-food restaurants. Since then, the city has installed more than 500 surveillance cameras at parks, schools, low-income housing complexes, immigration centers, gas stations, churches, abortion clinics, hotels, health centers, apartments, and addiction treatment centers. Now, the city is installing high-definition cameras at roughly 500 intersections at a time when other cities are scaling back because of privacy concerns.

Duggan and Craig insist crime has decreased in areas where the cameras are located, but they have been unable to provide documents to back up their claims.

‘To put a technology in place in a city of color that is already over-policed just opens the door for a host of problems that could likely get people caught in the system who shouldn’t be.’

tweet this

"The goal of these surveillance cameras is to make Detroit's residents feel safe going about their daily lives," researchers at Georgetown Law's Center on Privacy & Technology wrote in a study entitled "America Under Watch: Face Surveillance in the United States. "Adding face surveillance to these cameras risks doing the opposite."

The surveillance cameras are monitored around-the-clock by civilian and police analysts at Detroit's Real Time Crime Center, a large room with rows of computers and floor-to-ceiling screens displaying live surveillance feeds at DPD's headquarters on the outskirts of downtown. That's where analysts have been quietly using facial recognition technology for nearly the past two years.

Although the city purchased a system that enables police to scan faces from cameras, drones, and body cameras in real time, Craig says police only feed screenshots into the software.

"We do not want to do real time, and don't plan to," Craig says.

To strike a balance between public safety and privacy, Craig says police only use the technology after a felony is committed. He emphasized that the technology would not be used on minor crimes or to identify witnesses.

DPD's policy raises red flags

The trouble is, the city policy that lays out the ground rules for using facial recognition makes no mention of those restrictions.

"In the Detroit Police Department's current policy, it reserves the right of the police to drastically expand the scope of their system, even to include drones and body cams," Clare Garvie, co-author of the Georgetown study, tells Metro Times. "Why would you buy a system that enables real time when you can never use it?"

That policy was never approved by the Detroit Board of Police Commissioners, which was created to protect the civil rights of residents. According to the city's charter, police department policies must get approval from the commission.

Craig defended the police department's failure to get approval, saying, "We never tried to hide that we were using it."

"If we knew then what we know now, we would have gone before the commission," Craig says. "I had no idea that the response (to facial recognition technology) would be like this."

On July 11, protesters wearing masks demanded that the commission ban the technology. Earlier in the meeting, the most vocal opponent of facial recognition, Commissioner Willie Burton, was yanked out of his seat and arrested because the chairwoman wanted him to stop talking.

Craig later decided he would not ask prosecutors to charge Burton with a crime.

Craig's administration and the police commission are working on a more restrictive policy, but neither has made it available to the public. And whether the chief has enough votes to approve the use of facial recognition technology is unclear. The commission's chairwoman, Lisa Carter, said she also opposes the technology because it is prone to errors and is racially biased.

"The technology is flawed, and those flaws primarily relate to bias against African Americans, Latinos, and other people of color," Carter said at a July 18 commission meeting. "Such a flawed tool has no place in a police department servicing a majority Black and brown city like ours."

Calls increase for moratoriums

Garvie says policy restrictions are not enough.

"Policies are not sufficient. They are subject to change. That to me is troubling," Garvie tells Metro Times. "There should be a moratorium until there are laws in place."

Robinson, a Democrat who represents Detroit, agrees. He introduced a bill on July 10 to place a five-year moratorium on the technology to give lawmakers and experts time to research the technology's flaws and whether it's even constitutional.

"There needs to be a discussion on where the limits are and how the technology is used," Robinson tells Metro Times. "We need to discuss civil liberties and make sure local governments aren't overreaching."

Since then, Robinson said, the bill has picked up bipartisan support.

Massachusetts and Washington state have also proposed moratoriums on facial recognition systems.

The current state law requires the Michigan Secretary of State's office to share its database of driver's license photos with law enforcement.

"We have worked with the FBI on specific individual cases, but we don't share our databases directly with the FBI," Secretary of State spokesman Shawn Starkey tells Metro Times.

The office shares the database with Michigan State Police and DPD, but it has not received requests from immigration officials, Starkey says.

A Detroit ban

Detroit Councilwoman Mary Sheffield is also working on a citywide ban with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union.

"There are very serious and legitimate concerns among residents," Sheffield tells Metro Times. "Studies have shown the technology is unreliable, especially with people of color."

If approved, Detroit would become the fourth city to ban facial recognition technology. Since May, the cities of Oakland, San Francisco, and Sommerville, Mass., have banned the technology. Amid backlash, Orlando and Boise ditched plans to use the technology.

Sheffield is also championing an ordinance that would empower Detroit City Council to decide how surveillance technologies are used. The ordinance also would require a public hearing so residents can weigh in.

Even without that ordinance, Sheffield says, the police department should have alerted the public before officers began using facial recognition. That includes working with the police commission to hammer out a policy that balances public safety with residents' concerns, she says.

If approved, Detroit would become the fourth city to ban facial recognition technology, joining Oakland, San Francisco, and Sommerville, Mass.

tweet this

"It's two years later, and we still don't have a (commission-approved) policy in place," Sheffield says. "I think that's backwards."

Despite the backlash and the lack of an approved policy, police continue to use the technology.

"Communities typically press the pause button" when there's overwhelming public concern," Garvie tells Metro Times. "The very first question is to ask whether the public wants the technology used on them. If they do want it, we have to figure out where to draw the line. Do we want to use the technology to identify witnesses and victims of a crime? Is reasonable suspicion enough to use the technology, or should probable cause be required?"

If the city is concerned about the public's opinion, no public officials are asking for it.

Duggan, who has quietly advocated the technology, broke his silence by attacking what he claimed were false media reports about police using the technology in real time. When asked to produce a single false media report, his office did not. In a deceptively titled letter to the public — "I oppose use of facial recognition technology in surveillance," reads the headline — Duggan conflates "surveillance" with real-time use.

"The Detroit Police Department does not and will not use facial recognition technology to track or follow people in the City of Detroit. Period," the letter states. "Detroiters should not ever have to worry that the camera they see at a gas station or a street corner is trying to find them or track them."

Duggan added, "If your loved one was shot and there is a picture of the shooter, wouldn't you expect the police to use every tool they can to identify that offender? Police never make an arrest just because there is a facial recognition match. But it is an important source of leads detectives can use to find the identity of the offender. I fully support the technology's use for that limited purpose."

But Garvie says city officials are failing to explain how the technology can lead to false arrests. For example, she says, police departments may send a photo based on a facial recognition "match" to witnesses of a crime and ask whether it's the person who committed the crime. If the witness believes it is, that evidence can lead to an arrest — or to innocent people being harassed by police.

"Sending a witness a photo that is the product of facial recognition can be highly suggestive," Garvie says.

Last week, Rep. Rashida Tlaib, D-Detroit, teamed up with two U.S. congresswomen to introduce a bill that would prevent facial recognition technology from being used at public housing units that receive federal funding. Detroit currently has surveillance cameras erected at several federally funded housing complexes.

"We've heard from privacy experts, researchers who study facial recognition technology, and community members who have well-founded concerns about the implementation of this technology and its implications for racial justice," Tlaib said in a news release. "We cannot allow residents of HUD-funded properties to be criminalized and marginalized with the use of biometric products like facial recognition technology. We must be centered on working to provide permanent, safe, and affordable housing to every resident — and unfortunately, this technology does not do that. As representatives, we have a duty to protect our residents and are doing so with No Biometric Barriers to Housing Act of 2019."

Tlaib's bill follows two illuminating congressional hearings on May 22 and June 4, in which public safety experts and privacy advocates issued warnings about the technology. Legal experts cautioned the technology may violate the fourth and 14th amendments, as well as threaten free speech.

The technology is increasingly being used by the FBI and immigration officials at border crossings and airports.

"We shouldn't be using the technology until we can be sure people's rights are being protected," says Neema Singh Guliani, senior legislative counsel for the Washington Legislative Office of the ACLU. "By and large, people have been unaware of these systems and how they work."

Republicans and Democrats expressed alarm and called for a nationwide moratorium on the technology.

At the June meeting, Rep. Jim Jordan, R-Ohio, said a "timeout" is needed to avoid what he called "a 1984, George Orwell-type of scenario."

"No matter what side of the political spectrum you're on, this should concern you," Jordan said.

Alex Harring contributed to this report.

Stay on top of Detroit news and views. Sign up for our weekly issue newsletter delivered each Wednesday.