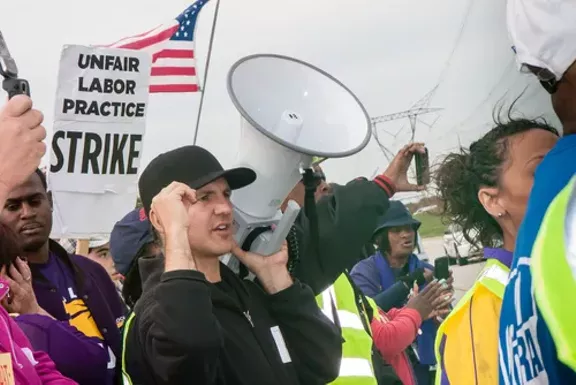

Image courtesy Shutterstock

Striking workers and supporters from an Illinois Walmart distribution center march against unfair labor practices, including wage theft, in 2012.

Here's something that should be as simple as mud: When you do a job for somebody, you should be paid for it. Seems like something so crystal clear that everybody would line right up behind it — Democrats, Republicans, Libertarians, Marxists, and Martians.

And yet Michigan's Democrats appear to have a fight ahead of them to pass a package of bills protecting that concept.

A package of proposed legislation designed to fight wage theft was announced earlier this week. State Sen. Jim Ananich (D-Flint) and state house Democratic Leader Sam Singh (D-East Lansing) discussed the bills on Monday, presenting a panel of people who’d dealt with wage theft at work.

One panelist, Lauren Rosen, said she was working at a restaurant in downtown Detroit when she noticed inconsistent tipouts that provided ample evidence management was claiming some of the workers’ tips. When she went to her bosses with the problem, she was fired. Rosen said the restaurant disbursed back paychecks a year later, but is still having problems compensating its workers.

Rosen also worked for a heath clinic last year, and employers made it difficult for employees to punch in and out, then changed their workers’ hours so they wouldn’t get paid for overtime. When Rosen complained, she was escorted out of the building, even though her photo was up on the corkboard in the lounge as “Employee of the Month.”

Also part of the presentation was Graham Kovich of the Restaurant Opportunities Center, a nonprofit workers' center fighting for the rights of workers in the hospitality industry. He recalled how, in 2012, while working at a chain restaurant, management distributed arbitration agreements for employees to sign. Those agreements included language signing away their rights to participate in class-action lawsuits. Looking into it, Kovich found that his employer was being sued for wage theft throughout country, and the agreements were a tactic meant to stifle their ability to seek redress in the courts.

Kovich also mentioned several other ways businesses steal from workers, from a local restaurant chain that deducted 15 minutes per shift from workers’ time cards to a high-end restaurant that charged bartenders $100 a night for coveted shifts. Kovich said that workers are allowed to be paid less than $4 per hour as long as tips bring them up to a full wage, but that the Department of Labor found noncompliance rates in the restaurant industry were higher than 80 percent.

But it isn’t only people in the food service business who have their wages taken. Take the case of panelist Dr. Erik Simon. He was a pharmaceutical scientist working for a small technology development company. Five years ago, he and other staffers were told payroll wouldn’t be met, but that the CEO had been instructed by the board of directors to ask staff to stay on while they negotiated bridge funding from an investor. Simon and others worked for no wages for several months, before finally asking to be laid off so they could collect unemployment. Then the company was dissolved, and they found out that the board of directors had asked them to keep working so they could peddle away the company’s assets for a profit. The workers took the matter to a labor lawyer, and a year-and-a-half later they were awarded about half the wages they were owed.

State Sen. Singh added that wage theft is also “very prevalent” in the building trades. He referred to a case on the west side of the state earlier this year in which 24 carpenters hadn't received $35,000 from the company they were working for. Again, working people playing by the rules bore the brunt of the problem, having their bank accounts frozen, finding themselves unable to ability to pay medical expenses, or having their cars repossessed. “These are real impacts that are occurring to real people,” Singh said, “hurting their families and them as individuals.”

The problem of wage theft in Michigan is aggravated by the way wage theft hits the most marginalized and lowest paid workers the hardest, given how many Michiganders live near poverty. That’s what a study by the nonpartisan Economic Police Institute, based in Washington, D.C., found in a report earlier this year. Findings included that Michigan employers steal as much as $429 million from the state's workers.

According to the study, the multimillion-dollar heist is the cumulative effect of many small cheats. It’s not always as blatant as an employer doctoring a pay sheet. Employees may be misclassified, or charges marked as “gratuities” may be diverted to overhead.

But is it "stealing"? Is that too strong a word?

Peter Ruark, a senior policy analyst for the Michigan League for Public Policy, says, “No, not at all. This is stealing from employees. … Doing things such as requiring people to come early and leave later, robbing people of their meal breaks, taking out deductions from their paychecks that aren’t supposed to be deducted, cheating people out of overtime … that’s all theft, and we do need to talk about it as theft.”

The proposed legislation would beef up staff at the state’s Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs, increase wage theft penalties, ensure those funds go back into enforcement, protect whistleblowers, and more. The proposed legislation would make repeat offenses of wage theft a felony, as well as retaliating against whistleblowers. The legislation, state Sen. Singh said, “will make bad actors think twice about stealing from workers.”

The measures are likely to face opposition from the GOP-led state legislature, who have used state law as an end-run around worker-friendly municipal initiatives before. It is also likely to face opposition from the National Federation of Independent Businesses, as reported by The Detroit News. The business group’s spokesman essentially said the group doesn’t endorse stealing from employees, but will likely fight any regulations on principle.

The thing is, this legislation really just scratches the surface of the problem. For instance, it’s unlikely the legislation will offer protection for the most marginalized of all workers, the state’s undocumented pickers who harvest the produce in the state’s agricultural sector. These workers regularly have their time cards falsified by their bosses, since they’re least likely to appeal to the government for help.

That said, these days, even marginalized workers are coming forward on the issue, including a case this year that involved performers at metro Detroit “gentleman’s clubs.” When workers in stigmatized professions are taking employers to court, it goes to show that the issue will not go away, even if "pro-business" groups balk about "regulation."

And why should they? To our mind, such protections aren't just good for workers, they're good for businesses too. Ruark agrees. “When employers break the law," he says, "it creates an uneven playing field where the scrupulous employers are at a disadvantage because other employers are underpaying their employees illegally."

This gives even the pro-business crowd an interest in ensuring the law is enforced.

“There may be differing views among legislators on the minimum wage, how high it should be, how often it should be increased, and all that," Ruark says, "but I think everybody should be in agreement that once a law is made establishing a minimum wage at a certain level, that law needs to be followed. You know, we are a society of laws. So this really should be a bipartisan issue to enforce the laws that are on the books and go after those who are not following the laws.”