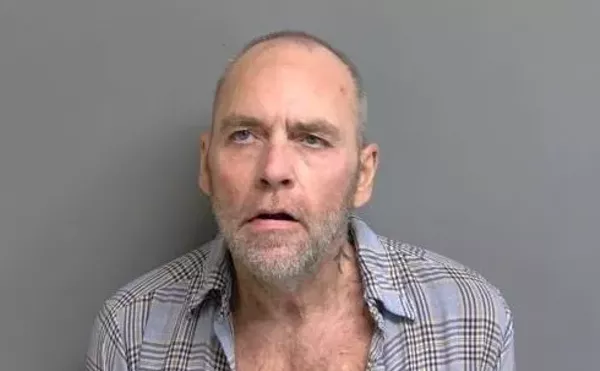

As a 20-year-old janitor for Detroit Edison in 1965, Darney Stanfield had no clue he would spend nearly four decades fighting to integrate and end discrimination at Michigan’s largest electricity provider.

As he worked his way up to middle management, Stanfield helped lead two successful class action lawsuits against Edison. Now, four years after the last battle ended and following Edison’s merger with one of the nation’s largest natural-gas providers, Stanfield says the Detroit-based conglomerate is reneging on its promises and reverting to old behaviors.

Stanfield and a group of plaintiffs have filed a 95-page complaint alleging the new company, DTE Energy, isn’t complying with a 1998 settlement and claiming DTE isn’t implementing 18 court-mandated programs aimed at enhancing diversity at the company. Further, the plaintiffs claim the company isn’t rehiring and promoting employees who were unfairly fired or demoted in recent years.

DTE representatives deny the charges; both sides meet Aug. 1 to attempt conciliation. If they fail, employees and the company could be headed back to court.

As for Stanfield, he’s fed up. After spending much of his career in and out of courtrooms, Stanfield, 57, retired March 31.

“I don’t need this grief. I don’t need the stress. I don’t need to go through the arbitration,” he says. “I’ve done two major battles with that company — and I’m not going to do a third.

“I’ve been fighting for all this time, just trying to get fair rights for the employees.”

In the 1970s, Stanfield helped lead a class action lawsuit against Edison that claimed the utility favored white males in hiring and promotions. The company fought the case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the employees were victorious. The struggle lasted 13 years. In the end, 400 black employees shared a $5 million settlement and Detroit Edison was ordered to implement an aggressive affirmative action program.

In the 1990s, Stanfield helped lead a second class action suit that claimed he and others were demoted or fired because of race or age when the company downsized. In 1998, Edison settled with the plaintiffs, 77 percent of whom were older whites. An arbitration board ordered the company to pay $45 million to be shared among 1,400 employees. As part of the settlement, the plaintiffs gave back $4.25 million in return for the company’s promise to implement 18 programs calling for such things as supervisor and employee training, minority recruitment, communication teams and dispute resolution.

The merger of Detroit Edison, an employee-owned company, with Michigan Consolidated Gas Company was final last June. When the dust settled, Stanfield was managing DTE’s career center, a hub for programs laid out in the settlement. When he was replaced by a new, younger manager, he decided to quit.

“I retired early without full retirement. I knew if I stayed, I’d probably end up in another lawsuit, and I didn’t need that. Physically and mentally, I don’t think I could stand it,” he says. “ I couldn’t stand being in that company another year.”

Round three?

Valdemar Washington is the “special master” appointed by the court to monitor the settlement for five years and ensure DTE complies with the 1998 ruling. The plaintiffs’ April 5 complaint, filed with Washington, asks for the implementation period, set to expire in July 2003, to be extended two years and rigorously enforced — or for the court to return the $4.25 million to the plaintiffs.

Washington thinks that the recent complaint is the gripe of a few, and not the majority.

“It’s not the big, bad company beating up on this class of people,” says Washington.

“There have been problems with implementation,” concedes Washington, adding, “this is not a one-sided effort.”

Washington says most of the programs have been fully or partially implemented. Three have not: People-skills training for supervisors; professional development; and communication ambassadors. With about 80 percent of the work done, the last 20 percent will be the toughest, he says.

“I disagree with the [complainants’] view that nothing is changed. The company has made progress, not as quickly as any of us would like, but progress is being made,” says Washington.

Stanfield, who still calls Edison “our” company, suggests Washington lacks a practical understanding. “His perspective is not that of someone who goes through it day to day.”

DTE says it’s working on the programs and doing much more than that.

“We take it very, very seriously,” says spokeswoman Lorie Kessler. “We are extremely proud of the progress [the programs] are making and the impact on our workplace. We’re working hard to institutionalize the programs so they represent more than a syllabus on a piece of paper, but represent a part of the fabric of our company and the workplace.

“What we’re trying to do is develop, through these programs and a whole array of other initiatives, a workplace built on solid core values, values of respect and integrity.”

But Jeanne Mirer, a lead attorney in the 1998 class action suit, says the company is “halfhearted” in its compliance and that there are problems with nearly every program.

“They’d start implementing the programs and then the person in charge would change, and they’d have to start all over,” Mirer says. “Others were not followed through. Some programs weren’t funded properly.”

The programs, she says, are a vital part of the settlement.

“They are an order of the court. They cannot be ignored. They are not mere suggestions.”

Christine Guerrero, a plaintiff in the case and administrator in DTE’s mapping and graphics department, says the company is “far behind on the programs.”

“It’s very difficult for minorities to get promoted and things like that,” Guerrero says. “There’s so many wonderful people at Detroit Edison, and we’ve had decent, good leadership, but they’re neglecting programs that can help everybody.”

Max Chambliss, a plaintiff in the 1998 case, says new management doesn’t understand what is going on.

“They were not there during the turmoil and strife and struggles, and they didn’t see the people who stepped up to the plate and agreed to negotiate with us,” Chambliss says. “The new people, they don’t even want to hear it.

“They’re slapping us in the face and we’re not going to take it.”

Another aspect of the settlement that has not been implemented to the plaintiffs’ liking is the requirement that people fired or demoted unfairly during the 1990s reorganization get preference for new jobs and promotions.

Washington says granting preferences for promotions and job movement “has had distresses we’re trying to work through.” As for the court order regarding 33 people who still qualify to be rehired, Washington says, “people on either side had different views of what it meant.”

“There have been some things they’ve done very well, other things not as well,” says Washington, a retired Genessee County judge now in private law practice in Detroit.

Washington will hear from both sides Aug. 1 as they try to resolve disagreements. If the employees are still unsatisfied, they can ask Wayne County Circuit Court to remove Washington from the case.

If the employees are still unsatisfied after that, they could sue again, though Mirer says there are no current plans to do so.

Mirer says the programs are very important to the plaintiffs.

“The plaintiffs were trying to say to the company, ‘If you do what you always did, you’re going to get what you always got: disgruntled employees who don’t trust the company, who don’t believe their complaints are being listened to, and you’re just going to get more litigation.’

“If you invest in your employees and develop ways to solve problems at the lowest level so they don’t fear management, there’s increased morale and a reduction in litigation.”

Lisa M. Collins is a Metro Times staff writer. E-mail [email protected]