The morning of Nationals I did my usual prep routine. My mom braided my hair and put it into a bun filled with three thousand bobby pins piercing my skull. She slipped me my lucky ice cream sandwich in secret, because if John knew that was what I was eating to fuel myself for a competition he would have lost his mind. He also would have disapproved of my dependence on a superstition. It was a tradition we thought best to keep a secret. I took my pain meds and walked to the arena.

I started on vault, same as Regionals. I wasn't going to do too many vaults in the warm-ups, just enough to feel ready. I stood on the blue felted runway as our warm-up began. My first time running to the vault I realized the step I usually take my hurdle on was way too far away from the horse than it should have been. My steps were completely off. The tape measure must have been a different distance from the horse than the one at my gym at home. I hadn't been allowed to get used to this tape measure during the practice day because of the stupid no flipping rule placed on me. Again, using different equipment in gymnastics is very difficult to adjust to. Everyone else knew their steps, since they had the day before to figure them out. Pure anxiety took over my body. Figuring out your steps takes at least four turns to feel comfortable before you're able to safely flip over the horse. I only had time for four turns down the runway total and only had the physical strength for two.

I had already wasted one of those two chances on realizing I had no idea what my steps were.

I ran down the runway again. My hurdle was way too close to the horse this time, but I went for it anyway.

Stupid.

My feet barely made it onto the springboard and I crashed onto the horse. My arms buckled on what should have been a back handspring onto the table, and the top of my head smashed into it from the missing support. I didn't go for the flip, but I still had the height and momentum to. My back landed flat on the mat hard after falling from nearly ten feet in the air. Smacking the mat with such force made a monstrous noise that echoed throughout the arena. All eyes were on me, watching as my eyes filled with water reacting to my fractured back crashing into the hard ground.

John helped me up. He didn't say anything. He didn't have to. I knew what he was thinking. He was mad I balked on my flip. If I had tucked and rolled my back would have been safe(er). He always told us to never balk because it was so dangerous.

"Are you good to compete or are we done?" he asked.

I nodded yes and said, "I'm competing."

My warm-up was over. The two times down the runway I was allowed were wasted and my body was nowhere near ready to compete. I walked back to the end of the runway and paced. I thought maybe I could walk off the pain. There were a few girls who had to compete before it was my turn, so I visualized. I knew two places I couldn't start my run. One was way too far away from the horse and the other was way too close. John could see my stress building up. He came to me, pointed to his temple and said, "Be tough up here, or don't go." He didn't want me to make another stupid mistake that would injure me even more. He reminded me how mentally strong I was. He reminded me to trust my mental training.

It was my turn. I walked up next to the runway and stood at the spot in between the two I had tried during warm-ups and failed at. I saluted the judges. The sound of the arena drowned out and I only heard the air inhale and exhale out of my nose for one final big breath. I ran, and my cue words streamed through my mind to match my body's movements. "Push, speed, too far from the horse . . . adjust, faster, hurdle, roundoff, block, twist, stick."

John clapped hard and whistled. He hugged me tight.

"Go sit down. We have some time before bars." I glanced over at the college coaches tables. They were all sitting today, taking notes and videotaping. There was no mingling; today was business. Today they were shopping for future investments.

Sixteen-year-old pieces of property.

***

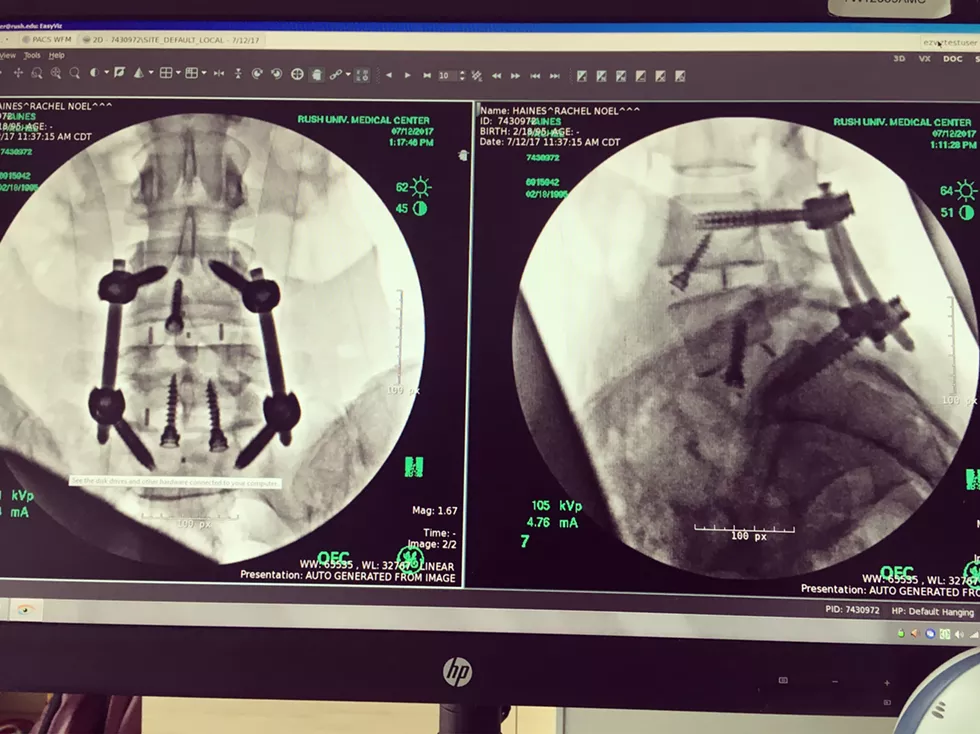

I left the meet exhausted — emotionally, physically, and mentally drained. I was so happy to be done, and I was beyond ready to heal. When I got home, I finally went to the hospital and got an X-ray and MRI. Sure enough, I had three fractures in my lumbar spine. I had felt right when each had individually happened. My MRI looked terrible. It had fractures everywhere, discs slipped forward, and discs bulging far into my spinal cord. The slipped discs were the likely cause of my back pain before the back tuck, but a month before, I had quite literally shattered my spine with one backflip.

I sat in the offices of the almost ten doctors I saw. I stared at my feet as they told me the same thing as the one I had seen before. My mom asked so many questions. My parents were there as I met with doctor after doctor, listening to my options. They heard all of them saying similar things.

"You need a very invasive spine fusion surgery that will make it impossible to come back to gymnastics."

"You have to quit gymnastics."

"You won't be able to control your bladder when you're 30 if you keep doing gymnastics."

I ignored them. I drowned out their words. They weren't what I wanted to hear, so I didn't listen. I was such a brat of a teenager. My parents absorbed everything and kept looking for more opinions. Maybe they kept looking because they knew I wasn't going to stop doing the sport that I loved. Or maybe they thought if I heard that I needed to quit from ten different doctors, I would listen.

But one doctor gave me another option. One doctor believed a comeback was possible. He told me it would be a long road to recovery, but that I could do it. I could continue to be a gymnast. I latched onto the words from one doctor and ignored the rest.

That one doctor was Larry.

***

Seasons as a gymnast blend together. After you compete for twenty years, meets don't stand out in memory unless something happened at them. Many of my meets stood out because I was in so much pain, so I am happy that the summer following my junior year in high school is hard to remember — it means nothing traumatic happened. It was my senior year and my last summer with Twistars. John had given me a new sense of leadership and encouraged me to be a source of guidance for the gymnasts younger than me.

This was the summer John let the seniors lead the horrendous running that we did every summer. I liked this new power he gave us, as it made me feel like I had a new motivation to do the running that I didn't have before. I even remember some days John would come and ask me how my body felt, and I would be honest and say that it was sore from a new conditioning list we were trying. He always believed me, and sometimes even told the entire team not to run that day because of my honesty. John's trust in those who respected him was unmissable.

That September, the other seniors and I signed our letters of intent to the colleges where we would continue our gymnastics careers. We had one senior going to UCLA to be on the coaching staff, three would compete at Western Michigan, one went to Ohio State, and I went to Minnesota. We all confirmed that our time with gymnastics wasn't over, and John once again had gotten a full class the opportunity to continue at a college level.

I loved the class that I graduated with. Together, we were a group of solid leaders who meshed wonderfully. We had bonded so much that we planned a trip to Disney together after the conclusion of our final meet the next season. We had been through everything together. One of the girls had even broken her back at the same time as me. We did rehab together, stretched together, and saw Larry together.

My back still throbbed during every practice, and my legs continued to get more and more numb. Larry kept encouraging me and kept working with me. I continued to see him every Monday even though I was doing 100 percent of my practices. He had informed me that continuing to see him would be vital to maintaining the pain level I had and not letting it get any worse. He told me that my sessions with him had transitioned from healing therapy to preventive measures. He warned me that if the treatments stopped, my back would hurt worse. He told me that if this happened, I would no longer be a gymnast. I was questioning why the therapy stayed the same when it was meant for a different purpose, but my fear of losing gymnastics outweighed every discomfort I had. Larry was still willing to work with me through my pain, so I was willing to push past how he made me feel. He was fighting to keep me as a regular visitor.

A consistent quiet victim.

***

Shortly after the season ended, things started to change. Our male head coach stopped coming to practices. There were rumors and tons of tension on the team. The freshmen were kept entirely in the dark until one day an article was published.

One of my teammates had come forward as a victim of our male coach, and our team was in shock. It seemed the upperclassmen were in on the details long before the news came out. They all knew which teammate it was and what the allegations were. We freshmen, on the other hand, were left completely in the dark. We had no idea what was happening besides the fact that one of our coaches was never going to be returning to practice. His wife, our head coach, remained.

Our team began to self-destruct. Some of the girls took the side of the victim, claiming to have also been made to feel uncomfortable by advances by our coach. Some of us had no idea what was happening. There was a clearly defined line that divided our team into two armies. Our close-knit culture crumbled.

Time kept moving and we kept practicing. The gym had the largest elephant in the room as we tried to work past the larger issue none of us wanted to talk about. The victim wouldn't admit it was her to the underclassmen, and it made us resent those who were older. Seniority trumped fairness and equality. We knew that everyone else except us knew what was going on, and it stung. Our team lost every connection we had built the previous year.

A few months later, we were hit with another brick in the face.

Our head coach was gone. Investigation after investigation happened that summer. I was interviewed so many times about things I knew nothing about. I had no information, yet my coach's job depended on the answers I gave. Because I was kept in the dark by the upperclassmen, I was watching my program crumble before my eyes in my second year there, with no understanding as to why.

Our team fell apart. Half of us resented the other half because they weren't telling us the truth. The other half resented us because we weren't being empathetic in a situation we knew nothing about. We went into the search for a new head coach with a clearly cold culture. The team interviewed three coaches for the open position: two outside applicants, and one in-house applicant. The assistant coach we had the year before decided to apply and had made it to the final round of interviews.

This wreaked havoc on the team.

***

Our assistant coach was named as interim head coach in October. This was midway through preseason, when we were supposed to be perfecting the smallest deductions in our routine, not finally solidifying who would coach us. Our male assistant coach left, and we remained with two open coaching positions. Those spots would officially be filled in December, one month before the season began. We went into the season unprepared, divided, and broken.

That year we defeated Iowa State, Michigan State, Ohio State, New Hampshire, Iowa, Maryland, and Rutgers. We went from a 27–6 record the year before to a 12–16 record. The reason our win number was even that high was because we faced teams we could beat multiple times in the same season. We were nowhere close to qualifying to Nationals for the second year. My pride in my gymnastics, and my team, was damaged. We were distant and disconnected as a team, and you could see it. We had lost our culture, and everyone could tell. Our success as gymnasts reflected our success as a team.

I had begun to break down mentally, physically, and emotionally.

My back pain reached a new level. It was becoming unbearable and made me resent going to practices. During the summer of 2015, I reached out to Larry for advice. I told him how much it hurt, and how I was forced to stop training floor because it hurt so much. My favorite event was taken from me because of my stupid injury. I cried on the phone with him. He knew I was calling for reassurance that I was OK; he knew I wanted him to say he believed in me; he knew I was calling him as my one last hope of continuing my career.

"I think it is time for you to be done. Gymnastics isn't safe for you to do anymore."

My world came to a stinging halt. What... what did he just say? Did Larry just tell me I was done? My chest burned red, my muscles started to twitch in seizure-like movements. My head clouded. My breathing turned into hyperventilating. The only man who ever believed in me didn't anymore. The only doctor who told me my comeback was possible said it no longer was. The only person who had ever given me hope took it away. He was so cold, like he had never cared. My mind was spinning. Everything I thought I knew, I questioned. Everything was fuzzy, except for the one obvious thing that was slapping me in the face.

If Larry thought I should be done, then I should be done.

I knew Larry rarely told people their bodies weren't able to do gymnastics anymore. Why would he? It would lessen his pool of victims. I knew when he suggested quitting, you quit. It was the last resort for Larry. His wildcard statement. If he played his wildcard, you knew you had reached the end of the deck.

I thought more often than I can describe about why Larry changed his mind at this moment.

What was different then from all the times I had wanted his opinion before? Why did he stop fighting for me?

I have since figured out why. Larry was faced with a misconduct complaint in 2014, the very beginning of the storm. He was not charged, but in 2015, right when Larry told me my career was over, he was fired from USA Gymnastics for sexual misconduct. The claims were increasing. Victims were coming forward. He was getting scared.

Larry knew what storm was coming. He knew exactly what was going to happen to him because of the number of gymnasts he abused. He knew I was one of his victims, a regular and consistent victim. He cut me loose so I would stop seeing him. He hoped I would forget the "treatment" he had performed on me for six years. He tried to disconnect from everyone he had abused in the hope the storm would dissipate instead of continuing to grow.

Little did he know that the storm would grow to be more terrifying than his worst nightmare.

More informaton about Abused: Surviving Sexual Assault and a Toxic Gymnastics Culture is available from rowman.com.